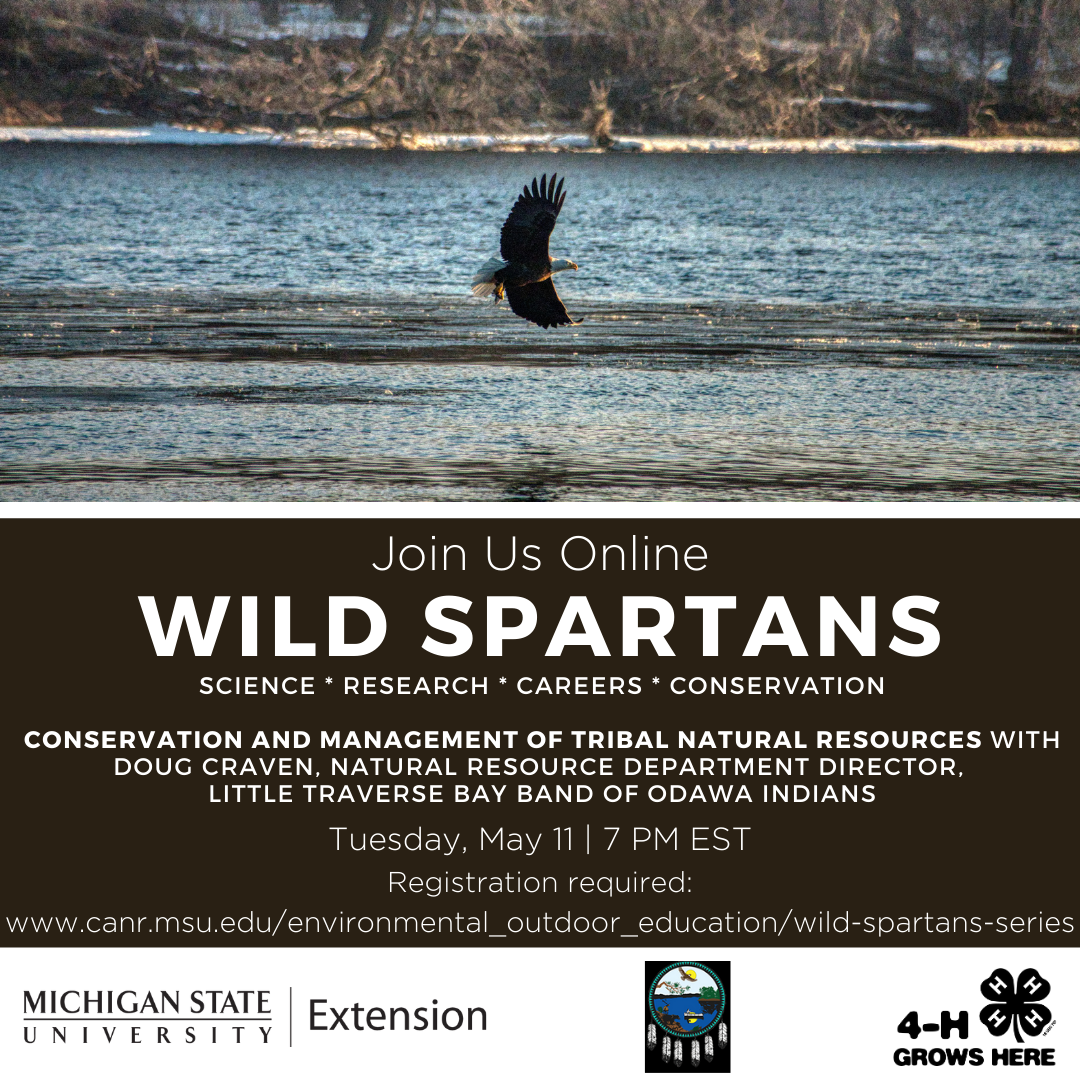

Wild Spartans: Conservation and Management of Tribal Natural Resources with Doug Craven; May 2021

May 11, 2021

More InfoIn this episode, we will soar the skies and jump into the waters to discover how one Michigan tribe is preserving our natural world. We will talk to a scientist about researching and protecting species with cultural significance. Meet Doug Craven, Director of the Natural Resources Department of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, learn about his field work and hear about the education and career path he followed to get there.

Find more tribal wildlife and fisheries resources here:

- Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians Natural Resources Videos

- Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) Educational Resources

- Wings of Wonder Rehabilitation Center

- National Eagle Repository

4-H can help you achieve your goals; learn about 4-H career preparation programs here.

Video Transcript

Thanks so much for joining us this evening on our Wild Spartans Wild Spartans monthly," Wild Science" Series. This program is created by Michigan 4-H, Michigan State University Extension, MSU, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and Michigan Department of Natural Resources, have over a 131 families participating from all across Michigan. We also welcome our guests from California, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Utah, Illinois, and Canada! We're very glad to see you all here. Some of you have registered for for several programs and come back month after month. And we love to see that. We're glad you're back for this program here in May. I'd like to take a moment to introduce tonight's moderators. There's five of us on the call. My name is Laura Quist. I am a 4-H program coordinator based in Wexford county, also on the call tonight are Anne Kretschmann, Veronica Bolhuis, Beth Martin and Dr. Alexa Warwick. And they're all located all across this great state of Michigan. Some of you might be asking what is 4-H? Well, 4-H is typically thought of as an agricultural program for youth providing programs on plows and cows. But we are actually the largest statewide development youth development organization in Michigan. And we focus on a variety of project areas. In this monthly series called 4-H Wild Spartans. We will explore careers in Wildlife conservation. We will meet scientists involved in field work, will follow along as they climb through bogs peer in to bear dens, mist, net songbirds, snorkel with fish and perhaps even tag some deer. We will meet researchers and learn about their field work and the education and career paths they followed to get there. And if you're interested, you can even join a Wildlife theme 4 H club in your own community. Tonight's program will last around 45 minutes. All participants are muted and your cameras will be off. If you have a question, you can type that right into the chat. And all of our 4 H staff will see that and be able to answer. We asked participants, change your name just to include your first name and your last initial. If you have a question that you'd like to ask our speaker, please use the Q&A feature right at the bottom of your screen there and type your question into there. And we'll be sure to ask that directly to our special guest at an appropriate time in the program. Also, as a reminder, tonight session is being recorded, but only the presenter and the moderators will appear on that recording. After we are able to close caption the recording, it will appear on the Wild Spartans webpage and you are free to share that with family and friends, school groups wherever you think that they will enjoy learning more about this. And now I will turn the program over to Dr. Warwick to introduce tonight's guest speaker. Thank you so much, Laura, I am very pleased to introduce Doug Craven. Since 2002, Doug has served as the Little Travers Bay band of Odawa Indians natural resource Department director, where he has committed to preserving natural resources. Doug feels that effective management of natural resources involves understanding human dynamics as much as the natural systems. His commitment to the natural resource community of Michigan includes having served on various boards and committees, such as the Great Lakes Leadership Academy Board, MSU Environmental, Natural Resources Governance Fellow, Getting Kids Outdoors in Emmet County and many others. He has over 20 years of private and public experience in Natural Resources. He has a dual degree in natural resource management and environmental studies from Western Michigan University. He's a father, a dedicated community member and an avid outdoorsman who appreciates exercising tribal treaty rights and continuing tribal traditions with his children and family. With that, I will turn things over to Doug and we are so delighted to have you tonight Doug and really appreciate you joining us. If you would like to share, Let me know if you have any difficulties finding that spot. Okay. So Aanii Ajiijak ndodem, ndaa, Waganakising Odawa Doug Craven ndizhinikaaz. So that's a traditional greeting, how we introduce ourselves. So I started off letting everybody know my clan is. So I'm a member of the Crane Clan. And then also where where I'm from a community I'm from. So wagankseen Odawa "wagankseen" is land of the cricket tree. So whenever you see Anishinaabemowin or the Odawa language, if you see there are certain places in Michigan that are named after. If you see I-N-G. The, of the word say ish, ishboming, dancing, some of those things that, that means place of. So that, that end part there, that ING that means place of. So I'm from the place of the cricket tree, which is up in the tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. As it was mentioned, I'm a member of a Little Traverse Bay bands of the Odawa Indians. In addition to being fortunate enough to be their Natural Resource Department director. Yeah, so we'll go ahead and see if we can share the PowerPoint. Sometimes it can be tricky. So I'm going to go ahead and give her a whirl and see see what we have here. Okay, So are you guys seeing that so far? Presenter view if you want to try to shift it to RSI, yeah, I see presenter view rather than the full screen. if you want to shift that. Okay. How does that look? Perfect! Okay. So yeah, we'll just kind of walk through a little bit here. Feel free to stop any, at any time. If there's questions or I look at this and view this as more of a conversation. So let's go ahead and get started. So we're located up in the tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. We have five programs within our Natural Resource Department. We have about 30 full-time staff and around upwards of 36 to 40. In the summer when we bring on college interns, we have a summer youth program, Youth Conservation Corps program where you hire a youth between the ages of 14 and 18 that work with our Department. Um, it's not a jobs shadowing program. It's an actual job where we have them come along and do actual projects for us. So they'll partner and they'll participate with each of our programs to get a little bit of experience in what it takes to be a Natural Resource professional. Some exposure to those, to those areas. But also they're, they're gonna do work for us as well. So real hands on the ground, boots on the ground type of work that we need. And so they're a great assistance with that. In addition, we teach them about treaty rights. And then we require them to do a presentation at the end of the end of the year. So September, after they leave us, we have them come back. And they do a presentation based on some field techniques that they learned, project or something of interests that they've learned. So we've had them do presentations on seining and fyke netting. Some survey techniques in regards to shocking, some stream shocking. In addition to larger projects or presentations such as Embridge Pipeline 5 those types of things. So here's a list of our programs. We have a Administration program, Great Lakes Fisheries program, Inland Fish and Wildlife program, Conservation Enforcement program, and environmental Services program. So we'll talk a little bit about each of those as we go. And again. Feel free to kinda stop anytime and ask questions if you have any. This is a shot of our Natural Resource Department building. We're currently have an annex, a separate building, and then we have a third office that houses our environmental crew right now. So this is a shot of Michigan and the 1836 ceded territory and our 1855 reservation. So we retained Little Traverse Bay bands. Odawa Indians is one of five tribes that were signatories to the 1836 Treaty of Washington. It's a, I like to call it a PD of trees, a treaty of peace. It was a treaty that was signed between the federal government and the tribes at the time. There's five political successors to those signatories. Little Traverse Bay bands is one of them. Sault Saint Marie Chippewa tribe is one. Bay Mills Indian community is another, Little River Band of Ottawa. Then the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa round out the five tribes that are political successors to the 1836 treaty. Some of the key things with 1836 treaty is there is things both sides we're looking for. On the federal side, that they were looking for acquisition of land. So they wanted to get title to that significant portion of Michigan. So it's about little over a third, almost half of Michigan. So it's pretty much eastern half of the Upper Peninsula and northern third of the Lower Peninsula. This is the Grand River down here at the South. In per the treaty language, it goes to the origin of the Grand River up to the origin of the Thunder Bay River. And then follows along out to Alpena. On the West Side of the Upper Peninsula here, this is the Escanaba river. And then it goes up to a point here. It comes back down to another point, the beginning of the Chocolay river. So this is near Marquette over here. So couple of things that the feds were looking for were to get title to the property. This was 1836, Michigan was entered into the Union in 1837, so this was a prerequisite for the territory to become a state. Some of the things that the tribes were looking for a were to stay here. This was just around the time of relocation. So there was a big effort on the federal government side. Disaster as policy really to forcibly move or relocate tribes from their ancestral homelands to West of the Mississippi. Little Traverse Bay bands actually had delegation that was sent down to Kansas to take a look at some of the properties down there that they are seeking to move us to in our contingent came back and said that it would not work when that do, there were no maple trees. Maple syrup, maple sugaring, is a big component of the lively hood. At the time, and continues to be a big part of our traditions now. And there would be no trees in order to make maple syrup. Little Traverse Bay bands. This is our reservation here. So it's one of the largest east of the Mississippi. It's about 300 square miles, includes a portion northern portion of Charlevoix County, about 80 percent of Emmet county also includes High and Garden Island. So the Odawa, Little Traverse Bay bands, Odawa Indians, we are coastal people. So water is very important to a commercial fishing, subsistence fishing, and the ceremonial use of water. The view of water not as just a resource but as a, is spirit and it has an essence to it. So moving to Kansas, there was no water either. And so the, our treaty, our delegation came back and said that there's no way that we can move out there. So one of the key provisions in 1836 treaty is Article 13 of the tribe stipulate the right, the hunt, in other usual privileges, the occupancy until the land is required for settlement. So that was a key component that our ancestors put in to that treaty. It enabled us the ability to stay in our ancestral lands. We would always have the ability to harvest from the resources. We have the ability to utilize resources for ceremonial and cultural purposes in our history, making black ash baskets and birch bark baskets and those types of things. So that was a very key provision. Another thing to note in treaties is that we, the Odawa and the other five tribes retained the ability to hunt and fish in gather, in lands that were ceded. It was not given to us by the federal government and certainly was not given by the State of Michigan. It was a part of inherent sovereignty as the original inhabitants of the land. That was ours to begin with. Our ability to govern, our ability to do these other things is inherent in that sovereignty as well. So we retained the right to hunt and fish. And another usual privileges of occupancy is very similar to law that exists today. You can sell a piece of property and maintain an easement to back piece of property. You can sell a piece of property and retain the mineral rights to it. You can sell a piece of property and retain the development rights where you sell it to another individual in their precluded from developing it. So this is called the usufructuary right And is very common today and it holds today as well as it did then. Treaty rights and exercise of treaty rights are part of that, that law, that they establish contract law. So treaty rights are very important to tribes, very important to Little Traverse Bay Band Art Department is probably one of the larger, more robust Departments in Michigan. And that's really shows how important Natural Resources are to our community, to be supported by our tribal council, our tribal chairperson our executive, and then of course, our membership to allow us to have such a large Department, again, really shows the emphasis on exercising treaty rights, being able to harvest, but also being able to protect those rights for the future. One of the core components of our management in tribal natural resource philosophy is the seventh generational approach. Where you look seven generations forward and you look at the actions, the things that you do now, the policies, the decisions you make now, not in the context of simply how will affect this generation or the current generation, but how that will affect the feature generations, seven generations into the future. And that's a little bit different than how certain things are done now. Our larger non-tribal community government is really set up to look at how you can get a direct benefit now and not necessarily looking at, maybe you would have to do some sacrifice now for the betterment of environment or for the betterment of Natural Resources, such that future generations, while I'd be afforded the same opportunity, or hopefully better opportunities to enjoy Natural Resources or the environment. So that's a real strong component of management of the Natural Resources that the tribes approach and that Little Traverse Bay Band. One of the things that really helps drive that home for me is that my generation, we are the seventh generation from the 1836 treaty signing. So those ancestors that, that sign that treaty. And I'm benefiting from those decisions that they made then, seven generations down the road. And so I hope that when we put things together, we're working on a number of things, the state of Michigan and the Feds and otherwise that, yeah, we can have that benefit to our future generations as well. Another quick difference here between how the tribes manage that Includes the Little Traverse Bay bands manage. And then I'll stop if there's any questions. Is we look at Natural Resource management and the utilization of resources a little bit differently than some of your non tribal organizations do. There is a, well known management philosophy that is based on sportsmen. Sportsmen harvest, sportsmen theory model actually. And it really looks at providing resources such that people can harvest them. And it's based on things such as fair chase or a thrill of the hunt type of mentality. And so we , the tribes, tried to look at it. Utilizing resources from an efficiency standpoint, from a respectful standpoint. So you're looking at harvesting a tribe. Tribal members may be interested in getting walleye or fish for consumption, so subsistence or for a ceremonial use. And so we're looking at efficient manners to go out and harvest those. Because you're looking at the end use of the resource for different purposes. We're not concentrating or focused on the act of harvesting as the end goal we're looking at it is the actual resource. And what type of credible use do you have for that is the end goal. So we're looking at efficient manners of harvest and reducing the amount of time necessarily that you're out. So there's less likelihood of tribe members, for example, wanting to spend money or having the ability to spend money on a charter boat for example, and spending the day and then catch 2 lake trout and then come back off the lake. They're looking at going out and setting gill net or something along those lines, maybe utilizing a spear in order to harvest a sufficient amount of fish in a short amount of time. that they then can provide to their family or be able to utilize for ceremony or those types of things. So that's just a little bit different end use type of perspective. And then I'd just quickly, the last thing that I think is a big key difference is that the tribes also have, we do specifically a want and waste provision. So if you are, if you harvest a species that you have to utilize that species. So if you get a deer tag , and go out an shoot a deer, you also have to make sure that you're processing that deer and then you're utilizing it. Underneath the current state of Michigan law, you're issued a dear tag and you go out and shoot a deer. Lawfully, you can let that dear hang and rot in your front yard, and there's no penalty to it. So it's really kind of a different view on use of the resource, how you get the resource and the end use of it as well. So I'll go ahead and pause there. If there's any questions? We do have a question. I'm so can you define the different types of fishery surveys that you guys do? Fyke and chunking? What does that mean? And what are the different species or age fish that work best for? Yes. So we do a variety of different types of surveys. So depending on what the target audiences, all right, so and what year. So if you're looking at young end of the year fish. So we do some, we've done some innovative fyke net. And seining, you're actually seining this certain like fyke net. So big long seines. Those are looking for a young end of the year, very small fish specifically, we do that for a whitefish and for Cisco on the Great Lakes to see if there's any natural reproduction. White fish are in trouble. They're real recruitment issues on the Great Lakes and we're very, very concerned about white fish. But we also do regular gill net assessments. So those are looking at adult fish. So that's on the Great Lakes. So you're looking at a lake trout and white fish at a certain degree. We're doing that with Cisco. We do with our inland program, shocking. So we have backpacks shockers on small tributaries or small streams that we're looking for young of the year. So Smelts, small Steel-head or Salmon. We have a tote back shocker that's a little bit bigger and you can drag along behind you. We have an electric fishing boat that we take out walleye shocking in the spring and in the fall to shock big anodes that hang off the front to shock fish. And then we also do a limited amount of fyke net, which is kind of an impoundment trap net that on inland lake to a certain degree. And then we do also, on about a five-year basis. State Michigan some, gill net surveying for sturgeon on our inland systems as well. So just about we also do trolling through troweling out on the Great Lakes and we also do some side scanner sonar as well. So any of the methods that are available that anybody's tried at any point we probably done that. Thank you, Can you tell us a little bit about what the differences between a fyke net and a gill net? Because we have a lot of the younger younger kids, so they may not know. Sure. I have. Let me see here. So this is an example of a gill net right here. So it's stands up, it's a set typically have these anchors on both side here, is a float line, then cork line, and then you have a lead-line. So straight up and down. And the fish will swim along its bottom set net . Though So usually targeting bottom set fish, depending on the depth that you set, you can target fish. So they're at different depths. We're targeting walleye would be shallower , if targeting lake trout and whitefish, depending on what time of year it is, they're going to be much deeper. So that's how you employ these. A fyke or gill nets actually can be pretty discriminating. You can target the species you're looking for fairly easily with those fyke net or a trap net. I don't have an example of one of those, but that is an impoundment net, these, these, the fish will get entangled into the gill net by its gills, via gill net and they are lethal. So if you don't get that fish out of that net within a very short amount of time, it'll die. These are usually set overnight, So one day they soak overnight and lifted the next day. A fyke or an impoundment net has very similar design to a certain degree that they have wings that look like, gill net, that their walls in the fish than swim along that into a central pot. The pot is designed such the fish can't swim back out of this as kind of a funnel design in the middle. And the fish will be moved down these wings, or hit these walls and swim down it. Then they'll get contained in the pot. But they're still free than to swim around in the pot. So then they're not as lethal and you still get some die off inside that depending on when you lift those pots. But then you can pull that pot up to the surface. And then you untie it, opens up and then you can net out with a dip net fish and lower, tie it back off from lower it and it can fish again. So those are some differences between fyke and gill net. Our trap, trap nets on the Great Lakes can be pretty big. 40 foot pots, they are tall pots. They can have leads that run a mile or so. And the inland those that we typically we call fyke nets. So they may have a six foot pot and a 100 foot lead on them, two leads or so. Have you ever caught anything other than fish such as the turtle? Yes. So if you are setting fyke nets inland, typically what our guys will do is they'll put a float in the pod. So those are typically set and more, if you're running into turtles, they're typically more shallow set. So you can put a float in the pot that and keep the back end of it up. And so if turtles or fish swim in, and a turtle comes in as well, it'll get caught in there, but it can get to the back that pot be able to you to breathe because that's not a targeted species and you don't want to injure turtles. So for setting shallow, most responsible agencies will put a float in the pot to make sure those turtles don't get injured. Great! that's all the questions we have for now. Thank you. Okay. I don't know if I can go backwards now. Yeah. Okay. So this is just some example of some of the work that our guys do. So this is a new project, relatively speaking, new projects, so this is a Martin. These are two Martin's right here. This is Lower Peninsula work. Martin Fisher are not very well known in the Lower Peninsula. One of the, there is, was a reintroduction of very limited number of Martin in the late eighties by the MDNR over by the Pigeon River Country area. So that is north of Gaylord. In around that area. There's a very limited number, less than 50 that were released one year. And then the plan was discontinued or the process was discontinued. So for the most part, Fisher and Martin were thought to be extirpated, or at least very low numbers in the Lower Peninsula. So two years ago we started doing some work in regards to Martin. And one of the innovative things about this and Fisher is that we've worked with a dog company or group where the dogs are trained to detect the scat. So the droppings, if you will, the number two of the Martin's and Fisher to determine if they're in the area. So they're very secretive. This is , they are in the weasel family there for the most part nocturnal. So it can be very hard to survey them or find them. So we were able to work with the dogs and get some positive scat samples. And subsequently we set up a camera traps system to survey, well not a survey. First we're going to do a abundance to see where they're at. And then we're going to work on some, develop some survey techniques in the future. So we use the dogs to determine an area, relatively speaking, where we thought Martin would be and then we went back out in the guys deployed Cameras, camera traps. When we say camera traps is just really a motion detective camera that, they're not necessarily baited with anything. Some are in other camera traps surveys, sometimes it's a piece of road kill, or it can be a scent. We've done some camera traps survey work with bears. You can hang bacon and or anise, which is the scent of licorice. So bears like that smell there. So those are some ways that you can do that for these guys here though. We're just putting cameras out the areas that we had some positive sign for them. So these are two Martin. So it's pretty new project first, pretty fun and innovative project of the guys do them in the winter and into the late spring. And they may kinda pull the camera as before summer. Now, on the bottom here is some work that we do with eagles. So Martin and eagle, they're both clan animals as well. So Agizzay, is an eagle. And Martin, they both have their clan symbols. And so clans are people belong to clans, through a, your family lineage. And they have different roles within the community. Historically that they've played, whether their teachers are holders of the language or leaders, or medicine people, those types of things. Protectors, police officers, law enforcement, those types of things. So that, that drive some of our research as well as that we're not only concentrating on your species that are harvestable, so your gain species, but we're also looking at some of these other non-game species or some of the species that are currently haunted or trapped. So Martin are not in the Lower Peninsula. An eagle are certainly not a hunted species. So we've done quite a bit of work with eagles. We have or do, we started monitoring in 2006 or so, we're monitoring about 12 less than 10 eagle nest at that time. And then we've been up to 30. And this year the guys told me that we're doing about 50 eagle's nest now. So that is an area around the reservation, includes the islands again and then gets over into Cheboygan and Charlevoix County. So we've really seen a resurgence in Eagles were finding through research that we've done that they're not as adverse to a human conflict as once thought, used to be thought of as a Wilderness species that you needed a minimum of 50 square miles of no roads or very limited human impact. And we're finding that's not the case, that they're much more resilient than originally thought. The reason why we believe that we're seeing a resurgence that we are now is really the success of the Clean Water Act. And it's taken now since '72 till now. So not quite 50 years, but quite awhile for those legacy chemicals really to work their way through the Great Lakes. So inland cleaned up a lot quicker in certain areas. But those chemicals, really persisted PCBs, DDT were out in the Great Lakes for quite awhile. And those chemicals affected the Eagles by weakening the eagle shells or the egg cells such that they weren't viable, so they just really weren't reproducing very well. But we're now seeing that their reproduction or the rate of success is doing very well. And so we do surveys in the spring. specifically for recruitment, we go out and fly a nest to see if they're occupied. I keep track of those for new nest. We've done in the past here, this is an example of a telemetry study that we've done. So we would hire climbers. They would climb up into the tree and then pull the eaglets out, put them in a little bag, lower them down. And then we would fit them with a band. So you would know where they're from. And then we had a limited number that we put cell phone technology, backpacks on them. And so as they flew, you would find out where they were. They had to be within the range of a cell phone tower though in order to download. So this was part of a study there was, you know, at the time thought that there was a distinct difference between Great Lakes birds and Inland birds It really wasn't really well known where eagles went and how they migrated and how they dispersed. So, we really learned some valuable information from this. This is an example of one of the birds that we had. So it was banded on or near our reservation. And then occupied space significantly further south of us, this Grand Traverse region. And then it flew all the way up into the Hudson Bay Area and spent the summer up there. So that's quite a, quite a ways. We've had eagles as fly as far south as Alabama and as far north as Hudson Bay. And that was really innovative work. That really isn't well know. And again, it really helped move that science forward is kinda get an idea of where those, where those birds go to. The other thing again is that it once it got north of Sault Saint Marie, it was off the grid. And so we didn't find out where it was until it came back into cell phone range. And then all that information downloaded and we're able to know where it was. Guys also do some work with a piping plover that's endangered species out in the Great Lakes there. So they've banded a few those. They check bears, harvested bears. We also do work on the reservation in regards to bear abundance. So that this again is another a camera trap, a survey we've done in the past. We've done work in regards to DNA, which is kind of a mark and recapture study, where you get a piece of the bear's DNA from the barbed wire set that they would walk over and leave a piece of hair on it. At least these baited stations. And then you can compare that with harvested bears and get somewhat of a population estimate from that. This right here is a brown trout. So there's question about surveying so that you can kind of see right here. This is the tote barge that would pull electric , have these anodes off the front of it. And this is kind of an example. Can't really see the whole net but, here's a portion of the net that you would dip that. And this is one of the fish that they got out of the Maple river. We're doing some work there in regards to populations estimate as part of some Grayling reintroduction, Maple river as a candidate stream for a Grayling reintroduction. So we're doing a lot of work in connection, with MDNR and University of Michigan. and determining what kind of quality stream that is to see if it is going to be in fact available or can be a candidate for that. So that's our Wildlife, Fish and Wildlife program. This is just an example of our Environmental Services program. So they do a lot of water quality stuff for us and are doing water quality assessment over here. Renewable energy, this is our hatchery. So these are two walleye ponds out here. So we have a solar panel array out there. We have a small-scale hatchery. It's not production size. It's for education and for developing techniques in rearing. So we've done some really innovative work with determining how to rear Cisco. So that's a herring type species, a small species similar to white fish. So we're really hoping to build, to ramp that up and get some other partners, the feds and the state, to be able to use that technology and rear those in feature. We also do a lot of streams. Upgrades stream culvert. So culverts are kind of pinch points. They create velocity barriers on one side or they can create flooding on the other. If they're undersized, which will warm up the system. So they're really not good for fisheries management. So we work with CRA, Conservation Resource Alliance to get a number these replaced with a natural bottom system in a timber bridge. So to remove these culverts in order to have better fisheries. Cool the streams down and to reduce some of these velocity barriers. So that's some work our Environmental Services crew does. We also have a Conservation Enforcement programs, so we issue around 800 licenses or so per year for inland hunting and fishing. We do about 20 licenses for a Great Lakes commercial fishermen and subsistence fishermen. So we have four full-time conservation officers that are charged with enforcing our rules and regulations. So we do have rules and regulations that govern our harvest. They have to comply with it to get licenses, to get permits, their seasons, there's bag limits. There's reporting, quite a bit of reporting actually that they had to do. In these guys, you're out making sure that they're following rules and regulations. They're also making sure that their (unintelligible) of a treaty rights not impeded that. There's not non tribal interference or fisherman or a hunter harassment in that regard. So they are out protecting members in that regard, and also protecting the environment, quite a bit of cooperative work with . MDNR, other tribes, non-government organizations, Sturgeon for Tomorrow. Our guys participate with them and will patrol streams that may have poaching or had poaching in the past in conjunction with a variety of groups. So there are a real good bunch of guys. So currently we have 4 Conservation Officers. So they do a variety of work for us, you know, in addition to patrol. This is an example here of Officers looking for, as part of the training, we had looking for a bullet fragments in potentially illegally harvested deer. This is just an example of training that we're doing. Matt is rescuing an eagle here. So this was a call that we had that was just off the reservation, or on the reservation in the Great Lakes. So this is Sturgeon Bay. That's beautiful natural area just south of Wilderness State park and tip of the Lower Peninsula. We had a call. He got over to the site there in saw the eagle out in distress out in the water. He was able to successfully bring it in. We have a partner organization, Wings of Wonder that does rehabilitation for us. Actually, we're now going to be taking over the rehabilitation and are developing our own eagle aviary in the Migizi rehabilitation center. Rebecca Lessard at Wings of Wonder has retired. But this specific eagle here, we took down to them. They're at Empire just outside of Traverse City. And what it was, this is a young bird, so this is a bald eagle. Bald eagles don't get a full white head until about their fourth year. So it takes a while for them to get a full white head to be mature. So your younger birds, oftentimes are mistaken for different types of birds. Most commonly as a golden eagle. A golden eagles are not common here. They migrate through, but they're not here in any specific numbers. And they also can be confused for turkey vultures. So this was a young bird here. He had in gorged himself on some fish and wasn't able to fly. Kinda got to heavy bogged down into the lake out there. So he probably would have perished had not Matt, Conversation Officer Robertson , been able to rescue him. We took him down to Wings of Wonder. She helped rehab him, took less than a week and he was ready to go and we brought him back to the reservation and had him released at our Powwow grounds. So that was a success story there. Matt also is kind of our Wildlife rescue guy. So that's an example of a little bird there. And he's also helped rescue deer, a fawn caught in fence before and that type of thing. So they get to do real hands on the ground stuff in regards to Wildlife, in addition to enforcing Natural Resource Rules and Regulations. Or I can pause right there if there's any questions are we gotta a couple more slides. YES! So Doug, can you elaborate a little bit on the plans for the aviary and a Wings of Wonder and will be open to the public? Is there an opportunity for volunteers, for 4-H members and that kind of stuff. Yes. So we're transitioning Wings of Wonder, Rebecca Lessard has retired. and so they actually closed their facility, dismantled it. So there is a void in Northern Michigan and the actually the eastern half of the Upper Peninsula, there is no certified eagle aviary or rehabilitation center anymore So as we have seen we have a higher number of eagles now, most that we ever had. And so those incidents for eagles to become injured is more prevalent too. The leading cause of injury for eagles is man, right? So it's car-deer accidents. We see a lot of lead poisoning now. So we have a, a program that we're encouraging our tribal members to transition away from the use of lead in harvesting dear, lead is very soft and it fragments and a lot or a certain portion of it will still be left in the gut pile or in your venison. actually, so those gut piles of discarded eagles come down and eat that. They're opportunist, as well as carnivores in as small as a grain of rice. a bit of lead size of the grain of rice can actually poison an eagle. So there's, there's, there's still a need for that. Electrocution is the second or the third leading cause of injury. But eagles, so there's still a number of eagles that are going to be in need of rehabilitation and a certain amount of those will not be releasable. And that's what you would put in your eagle aviary long-term. So yeah. We're in process right now fundraising to develop, to pay for the construction of a new facility. We have a tribal piece of property that's dedicated for that. We have as a design now, cost estimates, so we are in process of fundraising for that project right now, $600,000 project. We've raised around a $150,000. So we're still hoping to raise the remainder of that to get that facility up and running. And we are going to continue to, yes, work with Wings of Wonder. And hopefully they stay on as kind of our partner organization. Or we might transition into Friends of the Migizi aviary. But we certainly will be in need of volunteers and some assistance. To train volunteers to help run the facility, to be part of it. And then we do plan to have an education component to it. It won't be open to the public in terms of unregulated hours. It will be by appointment only. So we're looking to work with youth groups, 4-H groups, school groups, and get those scheduled in to the facility. Specifically when rehabbing Eagles, you really can't have unfettered access to that. That can really be a problem as far as having individuals on site in those types of things when we don't have staff around. So what we're looking to definitely have education component to it. We have within our hatchery program right now, We have a "Sturgeon in the classroom" program. Where we rear Sturgeon and provide those out to local schools. We have a curriculum that's developed and goes along with it has some culture into it, but also is designed to the core standards that teachers need. So it teaches math and engineering and those types of things in there. And they were looking to develop something similar in regards to the eagle aviary. We make some curriculum that we can partner with that. Obviously, we wouldn't be giving anybody eagle the take-home or put in the school. But we're looking at that type of thing. And if we get the right eagle, maybe we could have educational bird and be able to do some presentations, those types of things. But that's really going to be up to the birds that we get. Not all eagles are well-suited for education. Your non-releasable birds. It really has to do with their disposition and what type of bird they are. So they truly do have their own personalities as well. Do you have a target date. I know finances are an important piece that but you have a target date as to when you'd like to see that facility open? Yeah. We're very hopeful that we can do that this year. So we'd like to start getting some ground moved, you know, as early as this fall. If we could get secure $200,000, we think that we could build the the rehabilitation muse, at least to begin with, and then work on building the animal clinic, the lab portion next. Which would need another 200 or 200 thousand full. Then the third component would be our our permanent bird area. So the eagle aviary, so those non releasable birds. That would be our third phase there. So we're trying our best. We're hopeful that we can get to that. But the goal certainly as this year. Yeah, absolutely. Okay. Great. Thank you. Okay? So yeah, just a couple more here. So this is our Great Lakes program. So this is an example of Gill net boat. Small gill net boat. This is one that we do a little bit of research on and I think we have a picture of another one that we have. So this is a lifter on the front here and this is the gill net coming in and you can see a fish hanging from it here. So typically those are and the net comes up over the lifters right here, it's pulling. That's this wheel that spins. And so it's pulling the line through. This is a table. Fisher pick off of that as it comes through, the nets put back in the box over here. And then fish are put in this side over here. Again, this is an example of the gill net. Now this is just another shot of that boat. This is up in Lacross village, which is right on the reservation on one of our ancestral homelands there. This port here. So as example some of our Great Lakes Fisheries crew doing some, some work there. Again, this is just kind of another shot of a gill net boat. So again, here's that lifter it's bringing it in here. These are boxes of net here. And this is a white fish right there. This is actually one of our Tribal fishermen. Unfortunately, he passed unexpectedly the last year in a car accident. This is a Conservation Enforcement boat right here. So that's the Conservation Officer here. So he's boarding this individual out on the lake just to check them and make sure that, you know, nice fishing within the rules and regulations, that type of thing. Then the last couple of things that we have is our Treaty Rights Enhancement. So in addition to biologist and conservation officers, we also have some educational folks as well. This person's job is really to develop trainings and assist tribal members with hunting, fishing, exercising treaty rights. So there has been some loss over the years. Up until our tribe was reaffirmed in 1993-94, we were prevented from exercising treaty rights because it was illegal, against the law, for our members to do that. So there was some loss of tradition and, and there's been some loss as far as not having the right, not having available mentorship or those types of things. So we really are taking that seriously within the Department to help tribal members require that. Working with traditional Elders in getting some traditional ecological knowledge back into the community, they've been fairly successful. This is just an example of a few of the activities that we've done over the years. This is our shot of some hunter safety is part of that. We teach some Wilderness skills as well. So fire starting those types of things, so our hunter safety program is open to tribal members and members of the community. So we have a number of non tribal individuals that are participating in that. It's a little more robust than your average one, it's two days. So the teach international bow-hunter safety in addition to regular hunter safety. And we add in some of these other things, a little bit of orienteering, map reading, also some of the survival skills. Then we usually send the kids home when they graduate or the complete that with water bottle, space blanket. That's for their pack. Things to make them safe as fire starter, compass, and those types of things. Now this is an example of one of the workshops that we have is a deer-processing workshops. So that's one of the things that we identified as a need in the community. It can be very expensive to shoot a deer and take it to someplace to be processed. Those processing facilities sometimes get overwhelmed right around state deer season opener. So they're doing their best, but they can be questionable manners in which some of those animals are handled. So we really wanted to help tribal members to teach them if they had an interest in doing their own processing. So that has been beneficial. We have, this is some successful hunters from youth community deer hunt. So we provide mentors in firearms for those individuals that don't necessarily have them on a piece of tribal property that we have. So we bring youth out, community members doesn't have to be just youth, but anybody that necessarily hasn't had an opportunity to hunt or would like to get back into it. So that's another program that we provide. Again, this is another shot of our deer-processing class. We have all ages that kinda come and help and we will take those usually three deer from having skin on, to cutting them, boning them, all the way down to packing them, wrapping them. And sometimes we'll even grind the venison and send everybody home with a little bit of venison from that, so it's a nice community event. Unfortunately, last year we weren't able to do that. Hopefully this year things change enough where we'll be able to do some community events again. And then this is just a shot of some of our successful hunters. Deer hunters. So that's all I had. All right. Well we have Some more questions for you. So what does a typical day look like for you? Yes. So for me and I'm a manager, so I don't get out in the field as near as much as I like to anymore. So I am in charge of making sure that strategic plans are being met, that we're getting our goals met, funding, budgets, those such things. I do quite a bit of talking with our community members as they come in for their needs. Do a lot of higher level policy work in regards to federal policy that might impact tribes for Michigan, do lot of work with the State of Michigan in terms of Chronic Wasting Disease policy or trying to develop those types of things. So for me specifically, I out in the field as much. For our biologists, the rest of the guys, they spend, I'd say probably half their time out in the field. A field work is I really love the field work. Its fun. You get out. There, you go, you enjoy a beautiful area. But there's also a real need in component is in analyzing your data. So you got to come back in the office. You gotta take that information you gained from out in the field and process it. Develops reports such that we can manage effectively in really utilize that research. Again, those few activities to their, their fullest. So it can be about half and half for the rest of the guys. Okay. Can you talk a little bit about your career path and what motivated you to pursue that degree in Natural Resources and management and environmental studies, you know, how did you get started on it? Yes. So, you know, I think I was lucky to the degree that I've always been a natural resource type of guy. So hunting, fishing they have always been a passion of mine. And when I got to college, that wasn't really sure exactly what I wanted to do per se, and was able to get into a program that really met my interests and needs. I think it's important to get to college and it's alright if you don't know exactly what you want to do the day you graduate high school. If you can get into the university that fits you and the environment, the community fits you. Then I think you can look at some of these other options. So I changed my major once kinda going through there, I took an extra year to get done and ended up with a double major in Natural Resources and Environmental studies. That really spoke to me. Right? It felt good. I worked on a lot of policy. And so I felt that that was something that I definitely wanted to do after being exposed to that in the environment and that university setting. Going from there forward, I worked for some consultants for awhile . I worked for another tribe and ultimately was able to come back to my home community. So I consider myself very fortunate to be able to work in my community with with my community members. And in Michigan in general, I'm a big supporter of Michigan. I think we can do a lot better. There's lot individuals that I think they're looking towards governance and Natural Resources from common good type of perspective. In that based on our own personal biases or our own personal needs. Well, that's really good. What's the common good for Michigan? When you think back on your career? Can you describe what your best day was? My best day. You know, I I think my best day for me is I like, I love the Great Lakes. Not all of us get an opportunity to be on the Great Lakes near a Great Lakes State. Or they can be pretty hard to get out on the Great Lakes. So I had an opportunity to go out to be ride along, participate hands-on with some really innovative research out there, doing some global, the rare insect work out there, Michigan's Natural Features Inventory. So most beautiful day I was able to get out there and really see some of these really unique species of animal, species of plants rather that are only found in the duodenal communities of Michigan, Beaver Island Archipelago area that really get an idea of the different types. There's, some of them weren't really pretty, but they're, they're unique, right? And just to be able to participate what some experts in their field, and be able to recognize that we have these globally rare, these nearly truly unique gems within our community. And that I can be a part of that, that I can be a part of raising awareness on those. And then now take that and be able to be a part of helping develop some policy. In addition to being aware and help recognize the need for that. But really start working on some of these national policy or state-wide policy that can help these species. OK, And obviously you didn't come in just being a director. What kind of jobs, did you have prior to that to lead you into that position? Yeah. So I think I worked as, in college, in the state park system as a park ranger. And so those are great ways to really kinda get your foot in the door in terms of Natural Resources. So it also gave me an idea of what it takes to be a in Natural Resources. Sometimes natural resources can be glamorized that it's always sunny out and the lakes always flat and there's no arduous work to be done. That's not always the case. Sometimes you're out in cold weather, sometimes it's rough out and sometimes it's buggy out and you still have a job to do. So working in state park system will expose you to what Natural Resource manager was, but it was a job too. It also, I think afforded me an opportunity to interact with the public. So I think that's a key component of Natural Resources is really, in order to be successful, you really need to have better understanding of people in their tendencies are what their needs are, or what their interests are, and be able to move that. The animals and plants really they don't need our help in certain regard. They need us not to interfere with them. So if you just let animals and plants go and remove humans from the equation, they would do just fine. It's the human impacts that really are the ones that are affected them the most. So working for State Parks, I was consulting for awhile in the private industry there. Doing some NEPA assessments, environmental assessments, some wetland delineations. So those help give a good idea, private interaction and some idea what regulations are and how that impacts individuals. So yeah, developed a program for Department for another, tribe down in the south there and Nattawaseppe Huron bands and helped put together their Natural Resource Department and they're programmed down there. I worked on a number of grants regarding Wild rice introduction and some environmental issues, water quality and those types of things. So I think if you can get some diversity in the early part of your career, you certainly will help you and definitely give you an idea of what to expect in your career path if you choose to be a biologist or Natural Resource Manager. Okay? And as youth are preparing, thinking about school and classes that they should take or outside activities, What kinds of things should they be given to prepare themselves for jobs similar to yours? Yeah. I think sciences, Natural Resources, so, you know, biology, math. Yeah, I think those are going to be important. We'll definitely take a look at those, pursue those. Were looking for individuals that are critical thinkers, were looking for people that are going to be innovative. Want them to be thinking of these, these issues that face Natural Resources from a different perspective there can be a tendency within organizations. Federal organizations, state organizations. I like to say where they get institutional inertia, they kinda just roll and follow the same policy. Some cases the same bad policy or same management regime, just because they always have. So I think critical thinking, you know, is important. Developing some confidence in yourself, but also being able to critically receive information and use information and be able to move that type of information forward. So sciences and Natural Resources, biology, chemistry, those are all going to be important foundations. Being able to write critically is important. And I think having a well-rounded perspective. So your science guy, I'm a type analytical person. So if you've done any personality assessments, you, those types of things, I fall into that category there. So I think it's important if you are a scientist to really look at cultivating some creativity as well. So make some art or music or those types of things. And I really worked this and my kids. Make sure that you cultivate that side of your brain. as well. That helps with that creativity and innovative approaches. Yeah, I agree, well round kids are good kids, You talked a little bit about the staff that you hire. Does the tribe hire from outside. to fill some of those kind of jobs? or is it all within the tribe? Yes. So we have a tribal preference policy. So we'd like to hire tribal members. But unfortunately, we just don't have a large enough population base to draw on that. So absolutely any higher non tribal individuals from all over. So we just had an interview the other day or somebody was on. The West Coast Washington State applied. So we get grants from MSU, from Central from U of M Grande Valley, University of Idaho. You name it. We we we we have people that that come to work for us. Lake State, Yeah. We're always looking for opportunity. We have interns that are from all over as well. So from Arizona State you know, all kinds of places. So we absolutely hire a variety of people. And again, we're looking for that diversity of your critical thinking and how you can help achieve or look at some of these problems diplomatically. Ok, earlier you talked about some of the differences with Tribal Natural Resources Management. And what's one piece of information you wish more youth knew about those tribal Natural Resources and the management? Yeah. Well, I think number one is that there are tribal Natural Resource management entities out there. So for us, we do quite a bit of work within the tip of the lower peninsula. State of Michigan, is not always able to address certain things. And we have different perspectives in regards to management then the State. So I think the number one was at least a recognition that that's a, that's an opportunity for, for youth to come work for tribes. That tribes are involved in Natural Resource management in are big players in that regard. And then I think that the last key takeaway there is that there are different philosophies in regards management and tribes, generally speaking, are more of a holistic approach to management. Looking at a whole as opposed to siloing things off and try and domain is solely for deer or the species or that species or fisheries, forestry. And we're really looking at this holistic approach to management. So holistic management. And then earlier you talked a little bit about the ceremonial use of Natural Resources. Can you explain a little bit about those? So that the youth understands. Yes. I think there's, you know, there is a belief that most things have a spirit of their own or right to exist of their own. So we really look at Natural Resources, not from the perspective of conquest and conquering. Know what that resource can do for us. But how we cooperative can kind of work together. So we have a, a water Nibiish Naagdowen. is a statute, kind of our clean water statute, that really establishes that we want to be able to have water only be fishable, swimmable, but also to the degree from a contaminant perspective that you can use it in ceremony, that you can use it in water ceremonies. And that, that, that water in it of itself has a place where it has a right, if you will, to exist. And it's not simply there for our benefit or our use and that we can degrade it or contaminated to a degree that still allows us to use it, but it's not as pure as it was. So It's really this idea that don't just look at resources from the perspective of how that animal or that forest or those things benefit you individually or mankind. But also keeping an eye towards it has a right to be there as well. I just say thanks so much, Doug. This has been really fascinating. I know we're a little over time, but I didn't want to interrupt because these were really interesting just to hear your responses on all of this. So I don't know if there's any last piece of information you wanted to share with our audience tonight before we officially wrap up? Yeah, I think that the last thing is that we're always glad to see youth involved. 4-H is something all my boys have been through 4-H they did pig projects and those type things. And big supporter of 4-H. We're part of the advisory council here in Northern Michigan as well. But I think that again, just encourage youth to get out there Natural Resources are viable opportunities for employment. And we really need young innovative people to continue to move into those. So going to school, getting your degree, you can get a position that's meaningful and this is important. Oh, well, I'll just say thanks again for joining us and thanks so much everyone else for coming tonight too. Don't forget, as Doug said, there are 4-H clubs in every county across the state. So clubs get can explore Wildlife, engage in conservation stewardship in your own neck of the woods. And we'd love for you to contact your local Michigan State University Extension office to learn more about your 4-H program to get involved. This is our last program for this inaugural Wild Spartan series in 2020-2021. And we do have just two upcoming events to mention for anyone who wants to keep, you know, keep working in this area. The 4-H exploration days can put a link in the chat for that. Registrations already open. Those will be towards the end of June. And there's also a Bio-blitz project that we'll be starting in July. So we'd love to have anybody that's interested participate in those. And I will just put our last little bit of information up. I like to ask a quick couple of poll questions. So I'm going to launch that poll briefly. And as folks are wrapping up and getting ready to go on to the rest of your night, you would take a moment and respond to some of these questions. We would very much appreciate it. Again, thanks for joining and hopefully we'll see you in another. maybe next year if we can run this again or the the Exploration days or Bio-blitz. (Crickets Chirping)

Print

Print Email

Email