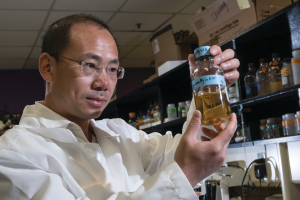

Bradley Marks: Killing bad bugs is what he does

Every year, approximately 48 million Americans become sick from food-borne illnesses. Causes including bacteria such as Salmonella and Campylobacter, and viruses such as norovirus and hepatitis A. And they’re all under the research eye of Bradley Marks.

Every year, approximately 48 million Americans become sick from food-borne illnesses, leading to 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The most common culprits include bacteria such as Salmonella and Campylobacter, and viruses such as norovirus and hepatitis A. And they’re all under the research eye of Bradley Marks.

“Our biggest goal is reducing food-borne illnesses,” said Marks, professor and associate chairperson of the Michigan State University (MSU) Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering. “Most of the food people buy is manufactured, and those systems – whether cooking, roasting, drying or toasting – need to be validated to ensure they’re delivering a safe product. That’s our sweet spot.”

To accomplish this, Marks and longtime collaborator Elliot Ryser, professor in the MSU Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, employ a unique blend of engineering tools and expertise on food-borne pathogens. Marks explains that, by focusing on improving the engineering aspects of the manufacturing process, their team is able to make novel contributions.

“Engineering has been a central strategy for me, careerwise,” Marks said. “I’m often the unusual person in the room, and I’ve found that if you’re the odd duck, you have a higher probability of coming up with something new and innovative for the project.”

By drawing on expertise in heat and mass transfer, fluid dynamics and math modeling – knowledge sets uncommon in the world of food-borne pathogens – Marks’s team has proven capable of addressing the design of food manufacturing systems as well as evaluating the safety of systems currently in use.

That distinct approach has led Marks and his team to many successes.

A primary foe of food processors today is the bacterium Salmonella. In the past few years, the pathogen has begun to appear in a wide range of common processed foods, including almonds, peanut butter, wheat flour and pistachios, where it is significantly more difficult to kill than in other potential hosts, such as chicken. Engineering methods to help food processors fight back have become Marks’s major focus.

Recently, the team helped almond processors find new ways to validate their systems against Salmonella through the use of a nonpathogenic surrogate organism. The Almond Board of California, which represents the entirety of almond production in the United States, made a voluntary decision to require all almonds to have gone through a process to reduce the presence of Salmonella before they go to market.

No commercial manufacturer would ever test their equipment with actual Salmonella, so Marks’s team helped validate a surrogate for them to use instead, an organism that mimics the properties of Salmonella without presenting any of the dangers. Their findings now constitute an important part of guidelines for the whole industry.

Marks’s work against Salmonella did not stop with almonds. A nonpathogenic surrogate had already been developed for use in pistachios but had not been adapted to the high-volume demands of commercial-scale processes. Thanks to the work of Marks and his lab, that has now been accomplished through the use of a biosafety pilot plant at MSU, which allows researchers to test pathogens on real food and equipment at the pilot scale, thus bridging the gap between the lab and industry. Additionally, the team was able to show that, by raising humidity or soaking the pistachios in a brine prior to roasting them, processors can significantly increase the amount of Salmonella killed.

Marks is currently leading a $4.7 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) uniting experts from five other universities and the Food and Drug Administration to find ways to reduce Salmonella in low-moisture processing systems.

One of the most valuable aspects of his research program has been delivering solutions at a scale practical for commercial processors.

“One of the most seminal conversations I ever had was with the vice president of a food company,” Marks recalled. “He told me that, while all the work we do in the lab is interesting and useful, it’s a huge leap to go from that scale to processing 10,000 pounds of food an hour. The fact that we at MSU can approximate that commercial scale is a cornerstone of our work. It lets us talk to processors in terms they’re familiar with and have confidence in.”

At the end of the day, though, Marks draws his sense of accomplishment from knowing that his work helps keep food safe.

“We’re doing something to prevent people from getting sick,” Marks said. “If we can succeed at that, I know we’ve done some good. Killing bad bugs is what we do.”

Name: Bradley Marks

Title: Professor, associate chair, Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering

Joined MSU: July 1999

Education: B.S., agricultural engineering, MSU, 1989; M.S. and Ph.D., agricultural engineering, Purdue University, 1992 and 1993, respectively

Hometown: Ida, Michigan

Muse (person who has most influenced and/or inspired me): Professionally, Fred Bakker-Arkema; I worked for him as an undergraduate. His expertise was in grain drying, storage and handling, and he did a lot of international work. When I first got into the field, I saw really advanced engineering being applied to make sure people had food to eat, and I remember thinking I could do all this math and science and it was really going to matter, it was helping food go where it was most needed.

Favorite food: Anything new. I like trying new foods, the adventure of it.

Book I’d recommend: The Checklist Manifesto. The author, surgeon Atul Gawande, shows how to apply the surgical checklist, the standard process for assuring that complex surgeries are carried out without mistake, to all kinds of activities. It shows the value of having even simple organized safeties for all kinds of fields, from airline safety to finance.

On my bucket list: Bicycle across America. The only trick is finding the four months to do it.

Favorite vacation: Family trip to the Canadian maritime provinces. My brother and I once biked Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, then my wife and I went back with our daughters years later.

On a Saturday afternoon, you’ll likely find me: Either attending events with my daughters or doing gardening and yard work.

Best part of my job: Making a difference in the lives of students – otherwise, why be a professor? I teach one class a semester, either an introductory freshman course or a junior required course, and I have taught several others at various times.

If I wasn’t a researcher, I’d be: Probably an engineer in the food industry. But this is the best gig I could think of having.

Something many people don’t know about me: I played tuba in the Spartan Marching Band, including a trip to the Rose Bowl.

Words of advice for a young scientist: Find your passion and work hard. I get a lot of students uncertain about the future, and I say if you aren’t sure about this field, you need to find the one you are sure about.

I went into this field because: I enjoy the technical challenge, but I am impassioned about doing it in a way that makes a difference in people’s lives.

Print

Print Email

Email