Michigan hop crop report week of August 10, 2023

Cone development is a critical stage for disease control.

Weekly weather review

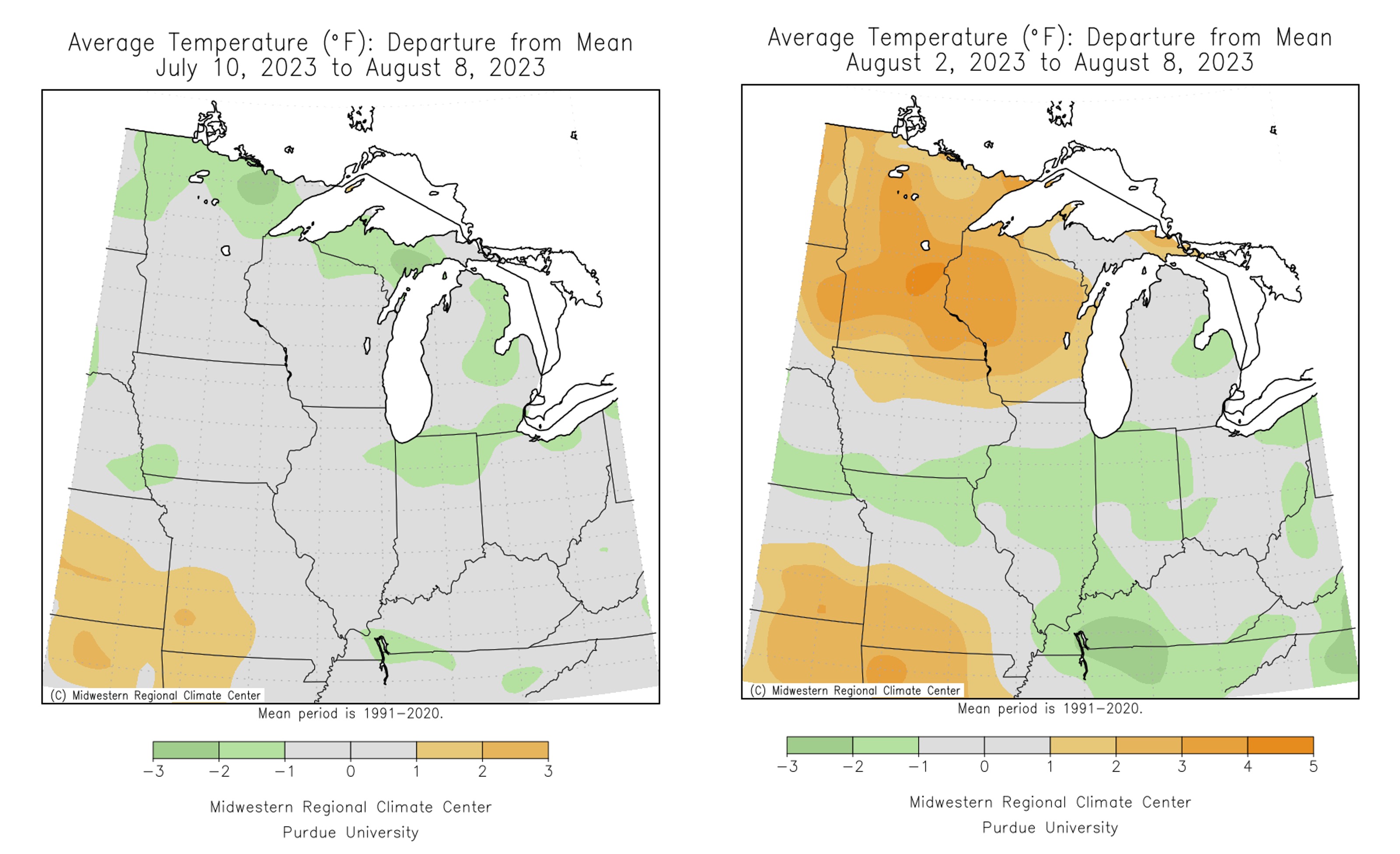

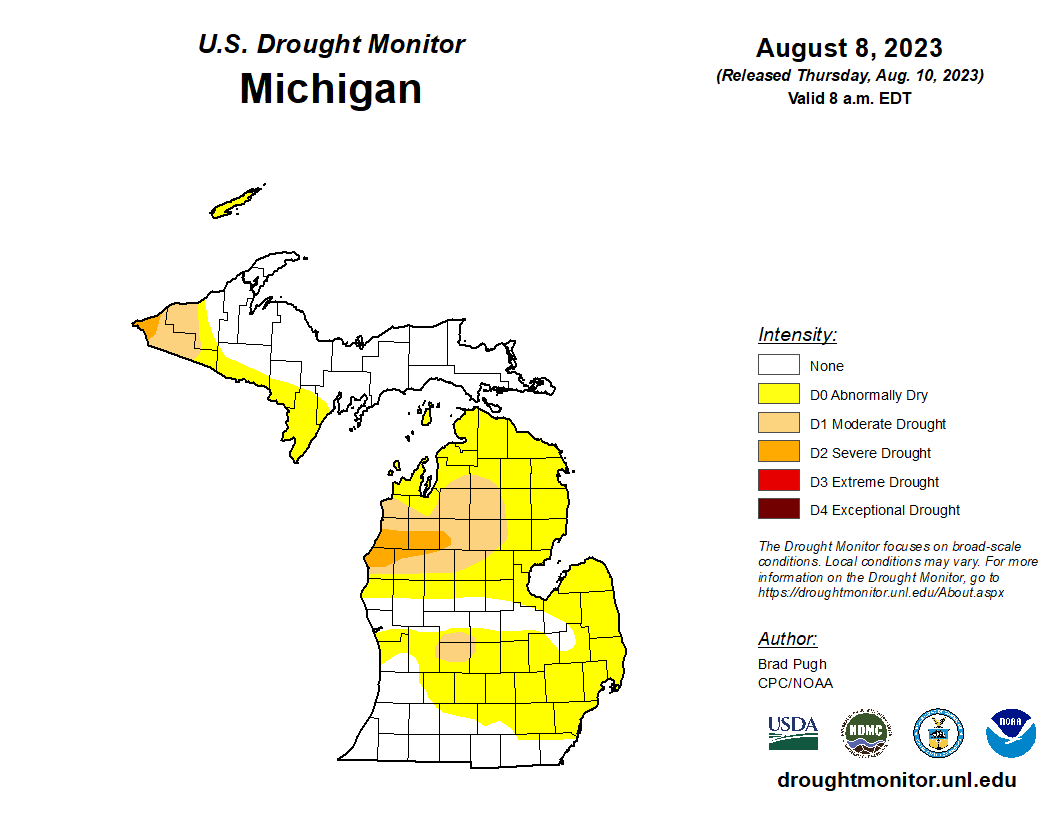

Temperatures over the last 30 days were near average throughout the west side of the Lower Peninsula, areas of the Thumb and eastern Upper Peninsula. Temperatures in northeast and east central Michigan were slightly below normal. In terms of precipitation, southern Michigan received above average precipitation while northern Michigan was below average. Recent precipitation should alleviate drought conditions.

Looking ahead

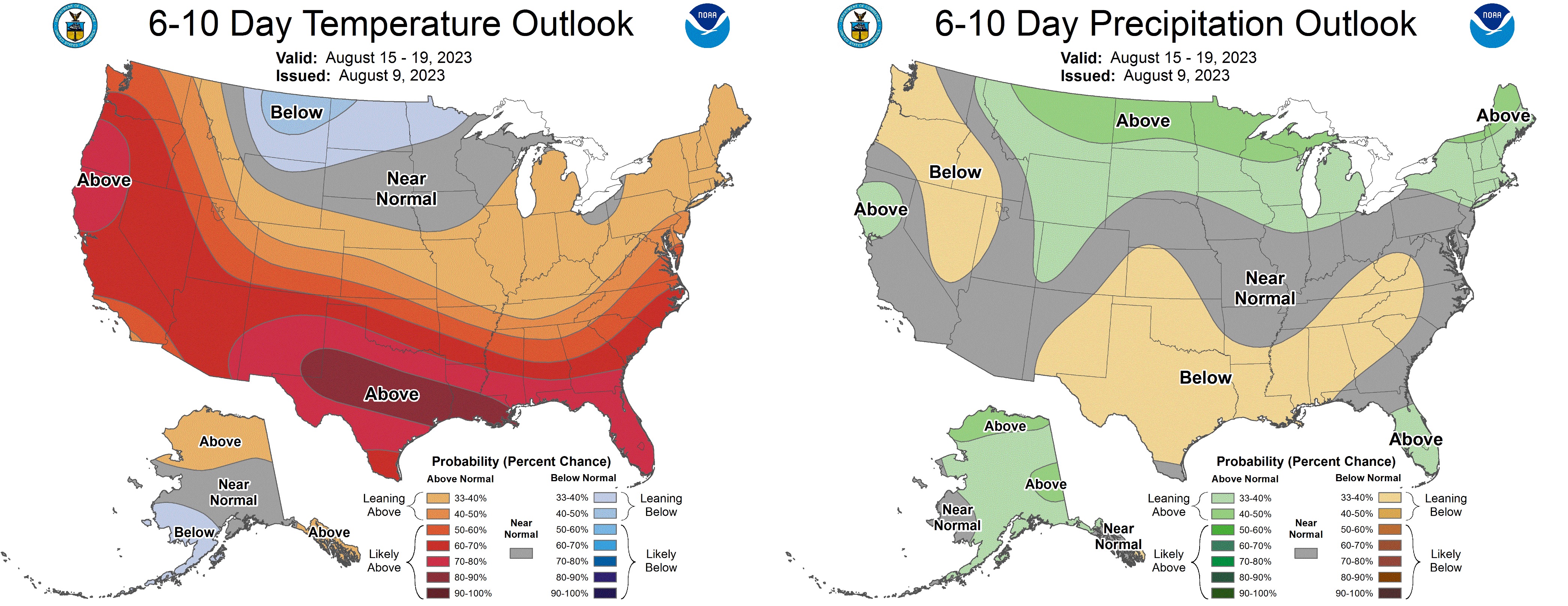

NOAAs 6-10 day outlook suggests slightly above normal temperatures and precipitation.

View the most recent MSU agriculture weather forecast.

Stage of production/physiology

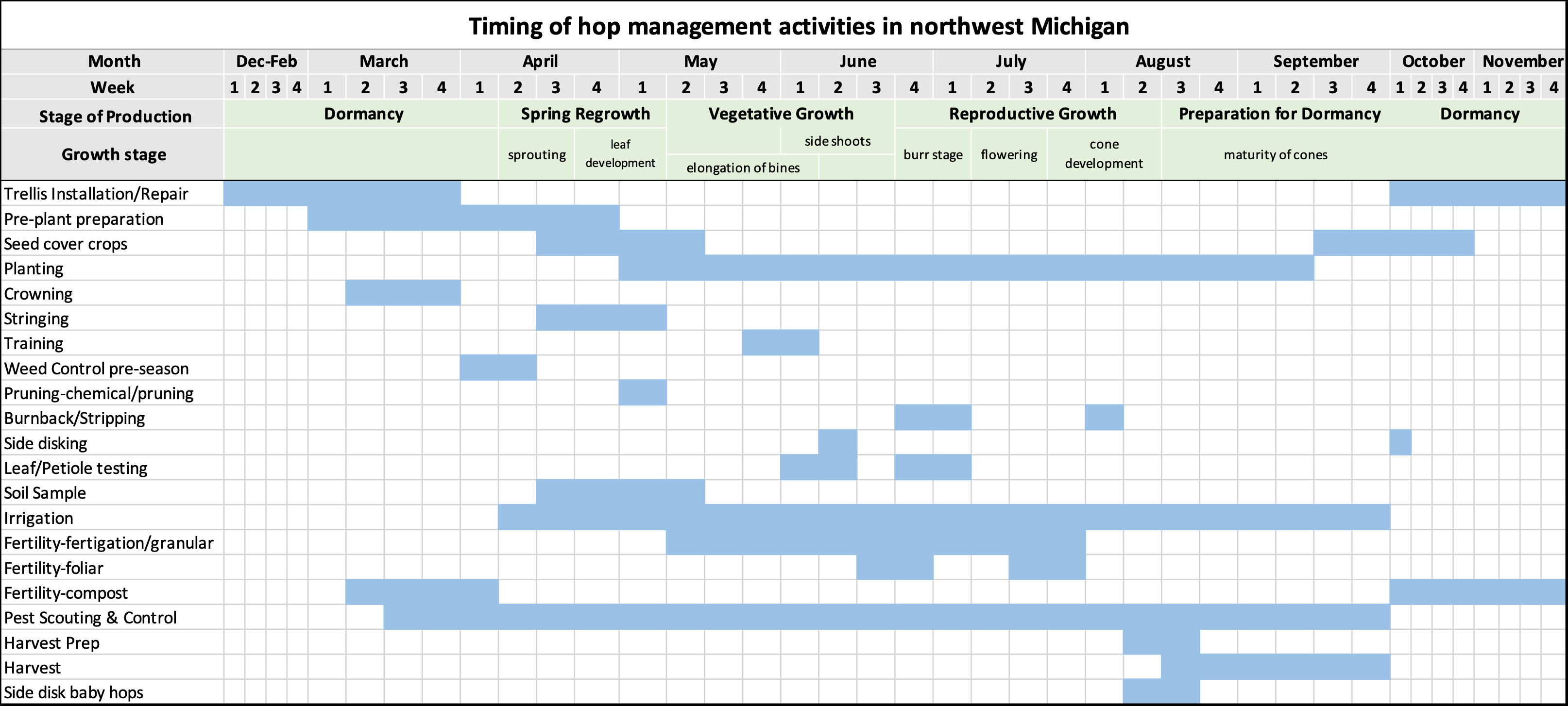

Hops across Michigan are in Principal Growth Stage 6: Flowering and 7: Development of cones, depending upon growing location.

In the field

Weeds

Grass weeds need to be treated when small for optimal control. Spot treatments for tough weeds like Canada thistle may be needed. Good weed control can be really helpful during harvest! Refer to the Michigan Hop Management Guide for weed control options.

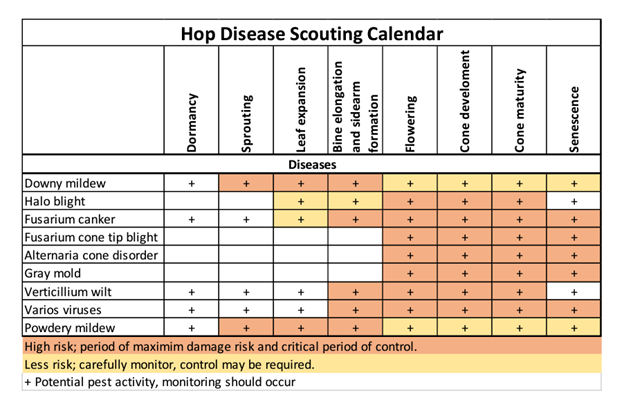

Diseases

As flowering and cone development progresses, growers should be making several critical fungicide applications to protect cones from multiple diseases, including downy mildew, powdery mildew, halo blight and associated secondary cone diseases.

Downy mildew

Downy mildew infection symptoms are visible in yards. Downy mildew is caused by the fungus-like organism Pseudoperonospora humuli. It is a significant disease of hop in Michigan, potentially causing substantial yield and quality losses. This disease affects cones and foliage and can become systemic; in extreme cases, the crown may die. Cool and damp weather during the spring provide ideal growth conditions for the pathogen.

Disease severity is dependent on cultivar, environmental conditions and management programs. Focus on proactive management strategies, including 1) sourcing clean planting stock, 2) clean crown management in the spring, 3) scouting regularly and 4) utilizing a preventative fungicide program.

Unfortunately, even when best management practices are followed, downy mildew can gain a foothold in Michigan yards due to high disease pressure, challenges with fungicide application timing, suboptimal spray coverage, fungicide wash-off, cultivar susceptibility or a combination of these factors. In addition, fungicide resistance and infected nursery plants may play a role in some disease control failures.

Downy mildew fungicide treatments must be applied on a protectant basis as soon as bines reach 6 inches in the spring (regardless of the presence or absence of visible symptoms of downy). If growers are planning to remove the first flush of growth by pruning, the first fungicide application should occur only after regrowth. Applications should continue season long on a seven- to 10-day reapplication interval. The time between applications may stretch longer when the disease pressure is low, particularly after cone closure. Several periods in the season are particularly critical for disease control: immediately before and after training; when lateral branches begin to develop; bloom; and when cones are closing up.

Covering young, developing bracts before cones close up is critical to protecting against downy mildew when conditions for disease are favorable. Getting adequate coverage on undersides of bracts where infection occurs becomes increasingly difficult as cones mature.

Refer to the Michigan Hop Management Guide’s section on downy mildew for additional management information, including fungicide options.

Powdery mildew

In addition to downy mildew, growers should also be vigilant in scouting for and managing powdery mildew, which may be a bigger issue this year with early hot and dry conditions. Powdery mildew of hop (caused by the fungus Podosphaera macularis) is an important but sporadic disease in Michigan hopyards. Seasonal powdery mildew disease severity is dependent on cultivar, environmental conditions and management programs. Focus on proactive management strategies, including sourcing clean planting stock, scouting regularly and utilizing a preventative fungicide management program.

Powdery mildew resulting from bud infection appears in the spring white stunted shoots called “flag shoots.” Flag shoots are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all shoots in a field and making detection at this stage very difficult. Secondary lesions become visible as leaf tissue expands and first appear as raised blisters, which quickly develop into white, round colonies. Infected burrs and cones can also support white fungal colonies or may exhibit a reddish discoloration if infected later in development.

Burrs and young cones are very susceptible to infection, which can lead to cone distortion, substantial yield reduction, diminished alpha-acids content, color defects, premature ripening, off-aromas and complete crop loss. Cones become somewhat less susceptible to powdery mildew with maturity, although they never become fully immune to the disease. Infection during the later stages of cone development can lead to browning and hastened maturity. Alpha-acids typically are not influenced greatly by late-season infections, but yield can be reduced by 20% or more due to shattering of overly dry cones during harvest resulting from accelerated maturity.

Conditions that favor powdery mildew are reported to include low light levels resulting from cloud cover, canopy density, excessive fertility and high soil moisture. Leaf wetness from dew or rain does not directly impact powdery mildew infection, but results from high humidity and cloud cover, which favors disease. Temperatures from 46 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit allow powdery mildew to develop, but disease is favored by temperatures of 64 to 70 F; disease risk decreases when temperatures consistently exceed 86 F for six hours or more.

Regular fungicide applications are needed to prevent infection and are applied regardless of visible symptoms. Appropriate timing of the first fungicide application after pruning is important to keep disease pressure at manageable levels. This application should be made as soon as possible after shoots reach 6-10 inches or regrow in pruned yards. For a complete listing of recommended fungicides and additional information, refer to the MSU Extension article, "Managing hop powdery mildew in Michigan."

Fungicide applications alone are not sufficient to manage the disease. Under high disease pressure, mid-season removal of diseased basal foliage delays disease development on leaves and cones by lowering inoculum and increasing airflow. Do not apply desiccant herbicides until bines have grown far enough up the string so that the growing tip will not be damaged, and bine bark has developed. In trials in Washington, removing basal foliage three times with a desiccant herbicide (e.g., carfentrazone-ethyl) provided more control of powdery mildew than removing it once or twice.

Established yards can tolerate some removal of basal foliage without reducing yield. This practice is not advisable in baby plantings (less than 3 years) and may need to be considered cautiously in some situations with sensitive varieties such as Willamette. The potential for quality defects and yield loss increases with later harvests when powdery mildew is present on cones.

Diaporthe

It is also important to note that the fungicides applied for powdery mildew control in FRAC groups 3, 7 and 11 have been shown in preliminary research to be effective against Diaporthe, a relatively new disease to Michigan growers. At a minimum, fungicides should be applied to cover developing cones from burr stage through harvest. You can read more about this disease and university efforts to address it in the MSU Today article, Finding and fighting a new hop disease in Michigan. Growers struggling with this issue may contact Erin Lizotte at taylo548@msu.edu for assistance.

Virus

Symptoms of virus are being observed. Hops are known to host several viruses and viroids that potentially impact profitability by reducing yield, quality and/or plant longevity. Several of these pathogens are widespread in Michigan and mixed infections of multiple viruses and viroids in a single plant are frequently found. The perennial nature of hops and common methods of propagation contribute to the accumulation of viruses over time.

Accurately diagnosing a viral infection can help growers in making long and short-term management decisions on the farm. For information on virus testing available through Michigan State University, check out the publication Viruses of Hop in Michigan.

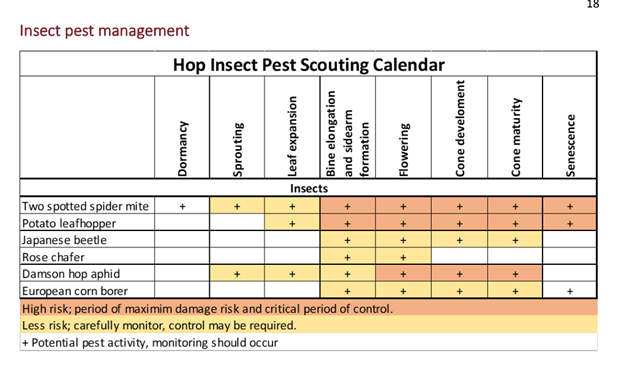

Insects

Damson hop aphid

Reports of suspected damson hop aphid are higher than typical this season. It could be because some growers are forgoing potato leafhopper imidacloprid applications under relatively low pressure early in the season.

Damson hop aphids (Phorodon humuli) are small (1/20 to 1/10 inch), pear-shaped and soft-bodied insects that may be either winged or wingless. Wingless aphids are pale white to green and are typically found on the underside of leaves. Winged aphids are dark green or brown with black markings on the head and abdomen. Aphids have two cornicles or “tailpipes” at the end of the abdomen.

Aphids remove nutrients and moisture from leaf and cone tissue with their piercing and sucking mouthparts. Damaged leaves may curl and wilt. Heavy infestations can cause defoliation. Cone feeding can cause wilt like symptoms in the cones and browning. When feeding, aphids secret sugary honey dew that can support the growth of secondary fungi and bacteria, most notably sooty mold. Sooty mold reduces photosynthesis and can make cones unsaleable. Aphids can also transmit viruses.

Damson hop aphids overwinter as eggs on Prunus species (genus of trees and shrubs that includes plum, cherry, peach, nectarine, apricot and almond), which are prevalent in agricultural settings and the landscape in Michigan. In early spring, eggs hatch into stem mothers which give birth to wingless females that feed on the Prunus host. In May, winged females are produced and travel to hop plants where additional generations of wingless females are produced.

As many as 10 generations may occur in a season with each female producing 30-50 offspring in her lifetime. Aphids do not reproduce as quickly in hot and dry weather, preferring more moderate temperatures and moisture levels. As cold weather approaches, winged females and males are produced, move back onto a Prunus host, where they mate and lay eggs before winter. We expect that this migration off of hops and onto plants in the Prunus genus will occur sometime in September in Michigan.

Monitoring for aphids should begin when daytime temperatures exceed 58-60 degrees Fahrenheit and continue through harvest. Aphids are not tolerated after flowering because cone infestations are very difficult to treat. Growers experiencing aphid infestations should consider that excessive nitrogen application and large flushes of new growth favor outbreaks.

Ideally, apply early season controls to limit population growth over the season. Pymetrozine is commonly recommended in the Pacific Northwest because it is effective and helps preserve beneficial insects. Additionally, products containing imidacloprid, spirotetramat and thia-methoxam are all labeled against aphids. Products containing synthetic pyrethroids (beta-cyfluthrin, bifenthrin, or cyfluthrin) and organophosphates (Malathion) are also labeled on hop for aphid management but are generally avoided due to the negative effect on beneficial mites. Organic options are also available. For more information, visit the Damson Hop Aphid Factsheet and refer to the Michigan Hop Management Guide.

Twospotted spider mite

Mite pressure has been high this season due in part to hot, dry conditions across much of the state. Growers should carefully monitor for twospotted spider mites. Twospotted spider mite is a significant pest of hop in Michigan and can cause complete economic crop loss when high numbers occur. Feeding decreases the photosynthetic ability of the leaves and causes direct mechanical damage to the hop cones. Leaves take on a bronzed and white appearance and can defoliate under high pressure. Intense infestations weaken plants, reducing yield and quality. Dry, hot weather provides ideal conditions for outbreaks. Scout carefully for mites season-long and treat while populations are at low levels, when mites are most effectively managed.

Refer to the twospotted spider mite factsheet for more information on identification and management.

Japanese beetle

Japanese beetle numbers have been very high in some locations. Adult Japanese beetles aggregate, feed and mate in large groups after emergence, often causing severe and localized damage. They feed on the top surface of leaves, skeletonizing the tissue between the primary leaf veins. If populations are high, they can remove all of the green leaf material from entire plants. Japanese beetle may feed on other plants parts, including developing flowers, burrs and cones.

Currently, there is no established treatment threshold for Japanese beetles in hop. Growers should consider that established, unstressed and robust plants can likely tolerate a substantial amount of leaf feeding before any negative effects occur. Those managing hopyards with small, newly established, or stressed plants should take a more aggressive approach to Japanese beetle management, as plants with limited leaf area and those already under stress will be more susceptible to damage. It is also important to carefully observe beetle behavior in the hopyard; if flowers, burrs or cones are present and being damaged, growers should consider more aggressive management as yield and quality are directly affected. For more information on biology and management, refer to the Japanese beetle fact sheet.

European corn borer

Based on the Enviroweather model, second generation adult flight of European corn borer has begun in most of the state. Growers are encouraged to continue to scout for this important pest based on its ability to cause significant damage, and the somewhat unreliable emergence patterns across the state. To estimate adult flight in your region, refer to the Enviroweather European Corn Borer Model.

European corn borer overwinters as larvae inside the host plant where it pupates (matures) in response to warming temperatures in spring. First generation flight of moths occurs from 450 to 950 GDD base 50, based on a March 1 start date for GDD accumulation. Currently, GDD50 accumulation in the Lower Peninsula ranges from 660-1,028. The second generation of European corn borer generally emerges around 1,450 GDD50. Continue scouting for adults, eggs and larvae to confirm model forecasts and make accurate management decisions.

Egg development is driven primarily by temperature, but generally eggs hatch in approximately 12 days. Newly hatched larvae then feed externally on leaves for approximately seven days before boring into stems and petioles where they continue to feed and grow. Once inside the plant, observations in hop indicate that European corn borer larvae damage vascular tissue, disrupt the flow of nutrients and water and impede plant development.

In hop, European corn borer larvae can be found in leaf petioles, sidearms, cone petioles (strigs) and bines. Their location and prevalence in the plant dictates the severity of damage. The most severe damage observed in Michigan hops occurs when hopyards are infested by first generation flight in June during bine elongation and subsequent sidearm and cone development stages. This early infestation greatly reduces yield and leads to variable cone maturity dates.

Focus on scouting for adult moths and eggs to allow for corrective management before larvae enter the bine. European corn borer eggs are smaller than the head of a pin but are laid in visible groupings. Eggs are white when first laid but change to yellow and then develop a black spot (the larval head capsule) just before hatching. Eggs are likely deposited on the underside of hop leaves in masses of 20 to 30 and covered with a waxy film. If available, you may have better luck spotting eggs in adjacent corn fields.

European corn borer larvae are light gray to faint pink caterpillars with a dark head and have dark spots along the sides of each segment and a pale stripe along the back. They grow to about 1 inch but start out very small at hatch and feed briefly on leaf tissue before boring into hop bines, and even hop leaf petioles.

European corn borer pupae are smooth, reddish brown, cylindrical and about a half-inch long and found inside bines. The European corn borer moth is about 1 inch long and light brown with wavy bands across the wings. The male is slightly smaller and darker. The tip of the body protrudes beyond the wings. Adult moths are most active in grassy areas before dawn.

Small European corn borer larvae are the intended target of insecticides, so monitoring for adult moth flight is critical to predicting the start of egg laying and the subsequent window of egg hatch.

For more information on European corn borer management, refer to the Michigan State University Extension article, “Be on the lookout for European corn borer in hops."

Potato leafhopper

Continue to scout for potato leafhopper, though most locations are reporting relatively low pressure. Like many plants, hops are sensitive to the saliva of potato leafhopper, which is injected by the insect while feeding. Damage to leaf tissue can reduce photosynthesis, which can impact production, quality and cause death in baby plants. To learn more about potato leafhopper, refer to the Hop Potato Leafhopper Factsheet

Stay connected!

Sincere thanks to the Michigan hop producers who provided timely input for the Michigan hop crop report.

For more information on hop production practices, please sign up for the MSU Extension Hop & Barley Production Newsletter, the free MSU Hop Chat Series and continue to visit Michigan State University Extension’s Hops website or the MSU Hops News Facebook.

If you are unsure of what is causing symptoms in the field, you can submit a sample to MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics. Visit the webpage for specific information about how to collect, package, ship and image plant samples for diagnosis. If you have any doubt about what or how to collect a good sample, please contact the lab at 517-432-0988 or pestid@msu.edu.

Become a licensed pesticide applicator

All growers utilizing pesticide can benefit from getting their license, even if not legally required. Understanding pesticides and the associated regulations can help growers protect themselves, others, and the environment. Michigan pesticide applicator licenses are administered by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. You can read all about the process by visiting the Pesticide FAQ webpage. Michigan State University offers a number of resources to assist people pursuing their license, including an online study/continuing educational course and study manuals.

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant no 2021- 70006-35450] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the North Central IPM Center. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email