Michigan’s Land-Grant Colleges and Universities Build a Connected System to Serve Tribal Communities

In 2018, NIFA awarded the two-year, $200,000 MILES grant to Bay Mills Community College and MSU Extension to help continue to build a foundation of connection, collaboration and learning between Michigan’s four land grant colleges and universities.

The State of Michigan has a long history of inhabitance by the Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi tribes, collectively known as the Anishinaabe. The Anishinaabek called Michigan home centuries before the arrival of Europeans in the 1600s. According to the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, Michigan is home to one of the largest native populations east of the Mississippi River.

Michigan Anishinaabe share common cultural practices and language called Anishinaabemowin. All tribal nations share common ties to the land. The tribes have their own unique structure of government, as well as political identities that vary from village to village. Tribal self-government incorporates an electoral process, governing documents including a constitution, and services that address community needs. Most tribes have their own judicial system whereby tribal citizen’s personal rights are guaranteed by tribal law, federal law, and tribal constitutions through a traditional dispute resolution method and a fair, just and impartial system.

Michigan is home to 12 federally recognized tribal nations and four land-grant colleges and universities: Bay Mills Community College, Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College, Michigan State University (MSU) and Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College.

On October 16, 2020, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Distinguished Teaching Professor and Director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, began her webinar presentation Listening to Indigenous Knowledge as Colleges and Universities: Building a Foundation with an Anishnaabemowin greeting, the language of the Anishnaabek people whose ancestral, traditional and contemporary lands surround the Great Lakes. Over 660 people from across the United States and Canada connected virtually to hear Kimmerer share how Indigenous philosophy and scientific tools can integrate to create a sustainable future.

The event was held as a part of the Michigan Inter-Tribal Land-Grant Extension System (MILES) grant, and symbolizes the continued effort of a foundation being built between Michigan’s land-grant colleges and universities.

In 2018, the National Institute for Food and Agriculture awarded the two-year, $200,000 MILES grant to Bay Mills Community College and MSU Extension, and recently approved an extension of the grant for a third year.

The purpose behind the grant is to help continue to build a foundation of connection, collaboration and learning between Michigan’s four land grant colleges and universities. Also to assist these four institutions to expand their reach in communities across Michigan, and especially to respond to the needs of citizens and members of the 12 sovereign Tribal Nations.

Serving All People in the Land-Grant System

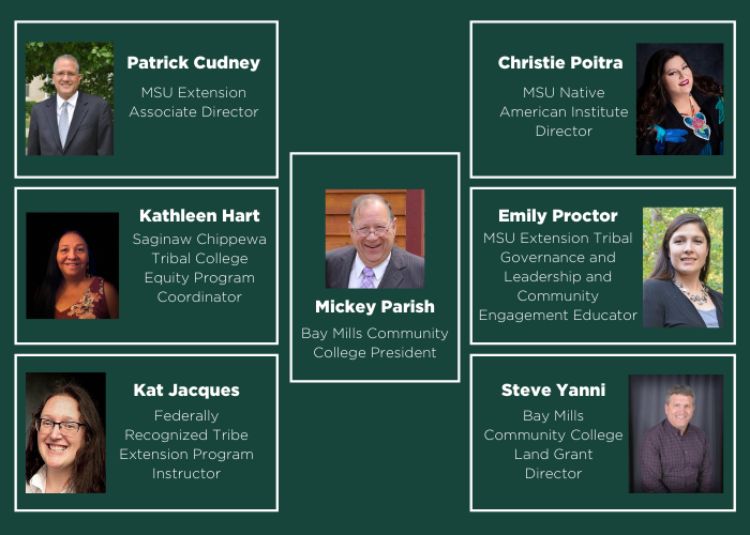

“Historically, this organization was created for home, farm, and mechanical education,” said Emily Proctor, MSU Extension Tribal Governance and Leadership and Community Engagement educator and citizen of Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians (LTBB). “It’s an organization that has beautiful intentions, so many resources and does great things, and also, it was created over a hundred years ago. The system was not set up to respond to what Tribes need.”

Proctor has spent her 12-year career with MSU Extension, working to build relationships with Michigan’s Tribal Nations, Tribal communities and instill a responsive network with MSU Extension.

“All of the cooperative Extensions nationwide have a mandate to serve all people,” said Kat Jacques, Federally Recognized Tribe Extension Program (FRTEP) instructor. “In Michigan, as well as every other place in the country, I think it’s very fair to say that we’ve fallen short on that mission when it comes to serving diverse communities and Tribal Nations are a part of that.

Jacques’ work as part of the FRTEP program is focused on how community food systems work and partnerships with those four tribal communities.

There are MSU Extension groups and individuals like Proctor and Jacques who have developed relationships or partnered on special projects over the years with Tribal Nations. Their work has helped the organization arrive in this place of inward- and forward-looking. But as Proctor described it, a metaphor for the history of collaboration with Tribal Nations is a piece of lace: with connections, but with holes in many places. And you can’t build a lasting foundation on lace.

MSU Extension leaders have also recognized the impact of historical and current programming efforts.

“We were concerned that work and partnership with Tribal Nations and the Tribal land-grant colleges had been episodic, where we had involved and engaged in projects and consultations, and we had at times received some grant support to do certain projects, but there was never a fully inclusive land-grant Extension system that serves Indian Country like most other communities across the state,” said Patrick Cudney, MSU Extension’s associate director.

Cudney, Mickey Parish, Bay Mills Community College President, and Bay Mills Indian Community citizen, and Steve Yanni, Bay Mills Community College land grant director, found inspiration for what a fully inclusive land-grant Extension system could look like in their own partnership between MSU Extension and Bay Mills Community College.

“The youth farm stand is a great example of how we’ve worked with MSU Extension over the years,” Yanni said. “It’s a program that MSU Extension has been offering for many years, but we’ve tailored that with our colleagues from MSU to meet the needs of the Tribal youth and the Tribal community, and it’s become a real success.”

This model of collaboration around programs that are culturally appropriate needed to be built into a foundation for how MSU Extension could work alongside all of the land-grant colleges.

“We wanted to create a more streamlined and synergistic land-grant system in the state of Michigan between MSU and the three Tribal colleges as we try to work together to meet the needs of Tribal Nations, Tribal citizens, and Tribal organizations as best we can,” Yanni said.

One of the greatest lessons MSU can learn from their Tribal partners is how to respond to the diverse needs of the communities they serve and how to use Indigenous wisdom and knowledge as a guide for programs and research.

Strengths of the Tribal Colleges Connected to Their Communities

Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College is an example for MSU on connecting with communities and structuring programs around Indigenous knowledge.

Kathleen Hart is the Equity Program Coordinator for Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College and a citizen of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe.

Hart gave an example of one of the annual events that take place, their one-week environmental culture camp for 12-17 year olds. She collaborated with the tribes Environmental Outreach Coordinator, Taylor Brooks, and other tribal departments to give the youth an opportunity to learn how the environment and our culture are connected, and to create an interest in the STEM areas.

“We tie in the environment and our culture to show how they interact with and support each other,” Hart said. “The kids learned about the strawberry and how it is good for your heart, that it is shaped like your heart, it’s medicine, it’s one of our sacred foods, and how the strawberry and our heart are connected to each other,” she said. “The youth also learned that cedar is one of our sacred medicines and that it is good for us, it works like our lymphatic system, which works as a circular system in both cedar and the human body. It also has a spiritual connection and a connection to the environment.”

Guadalupe Gonzalez, the USDA Extension Coordinator, works alongside Hart in the Land Grant Office at Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College.

“Gonzalez works with the community doing different programs such as canning, meditation and yoga workshops, making ribbon skirts and shirts, and beading and cooking workshops,” Hart said. ”Lupe also collaborates with tribal departments such as Seventh Generation, Ziibiwing Center, and the farmers market.”

Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College is also a model of partnering with other organizations to accomplish community goals.

“Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College hosts community workshops throughout the year and provides meeting space to the community,” said DeAnna Hadden, Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College’s land grant coordinator and Keweenaw Bay Indian Community member.

“We also partner with many local agencies to host and support other community events. We are also asked about donating and supporting additional activities in the community,” said Kit Laux, Office of Sponsored Programs director and Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Member.

From their perspective, the strengths that Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College brings to the MILES partnership are in the relationships they have and the relationships they’re growing.

“Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College has strong ties to our tribal community, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community,” Hadden said.

“And we are currently working on establishing relationships with other tribal nations in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan,” Laux added.

Just like Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College and Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College, Bay Mills Community College puts community needs at the forefront of their programming.

“We’ve asked the community which areas to focus on,” Yanni said. “We focus on a few different areas and health promotion is one that we focus on strongly. We operate a health and fitness center through the land grant department. Another area that we work a lot in is sustainable agriculture and food systems, and as a result of that, we operate Waishkey Bay Farm and do a lot of work with the community there.”

Bay Mills Community College models the role a land-grant can have in the life of the community.

“Bay Mills brings an understanding of how to successfully work within a Tribal community and identify what the needs are of the Tribal community in the ways that are respectful of Tribal sovereignty,” Yanni said.

I think Bay Mills also brings kind of a daring spirit or an entrepreneurial spirit in terms of - Bay Mills is willing to give most things a shot if they feel that it’s going to ultimately lead to the benefit of the people here at Bay Mills and the neighbors in the eastern Upper Peninsulas, so I guess it’s a kind of a fearless approach to try to do what’s best. Fearlessness, that’s what I would describe it as. And Bay Mills definitely has plenty of that. Steve Yanni

The Tribal land-grant colleges are driven by community relationships and needs, so the work that they do has a direct, positive effect on their communities.

“It has a bearing on the health and quality of life in the Bay Mills area that is so important,” Parish said. “It’s been a real change in the attitude of the community and you see a lot of people that are now growing gardens and their own food that never were in the past.”

All three colleges and the communities they serve are important partners for MSU.

“The history, the teachings, the language, all of those are important benefits that working with a Tribal college and a Tribal community have,” Yanni said.

Recognizing the strengths and the importance of creating an interconnected system, Cudney worked alongside Yanni to write the MILES grant.

“There is immense value and benefit that our 1862 land grant can receive from truly being in partnership with our 1994 land grants and our Sovereign Nation neighbors,” Cudney said. “They bring tremendous resources to this partnership.”

Building a Foundation on Relationship

The MILES grant recognized the work that all four Michigan land-grant institutions were doing in communities, and sought to provide a formal structure to connect people, programs and resources.

“The project was really kicked off in 2018 with the first ever Tribal summit that brought leaders together from all of the land-grant institutions in the state of Michigan and nine of our 12 federally recognized sovereign Nation neighbors,” Cudney said. “And that’s really where the broader concept was introduced about co-sharing of resources, working collectively to develop research and education programs to meet communities’ needs, and to do a better job of recognizing the resources that the 1994 Tribal colleges bring to the table.”

Since 2018, a MILES committee has met once a month in order to connect and collaborate. There have been tangible outcomes from the partnership, such as projects, programs and inclusion of Tribal Nation leaders at major MSU Extension events, including their annual fall conference.

“We’ve seen a hemp project come out of this in partnership with Lake State, MSU Extension, Little Traverse Bay Band, Ziibimijwang Farm and Waishkey Bay Farm with Bay Mills,” Proctor said. “We’ve seen articles written out of these partnerships, an increase in the Tribal Nations lead program. I think a key piece has been the conversations we’ve been having on what projects we have been doing and how can we do it in a different way or better.”

How can MSU Extension do research and programming better? By structuring around Indigenous knowledge and culture.

“Some of the biggest changes I have been seeing internally has been the integration of Tribal knowledge,” Proctor said.

Jacques gave an example of how MSU Extension, Bay Mills Community College, and Bay Mills Health Center program staff work together to co-plan and co-create programs to integrate Indigenous knowledge and culture and meet community needs.

“At a workshop, we had Dean Baas from MSU Extension doing the rainfall simulator to show the importance of cover crops and protecting soils and preventing erosion,” she said. “And alongside, we had a community member from Bay Mills demonstrate how to use fish waste from fish to enhance soil health and vitality. The community member demonstrating the appropriate depth and amount to be planting those under corn, beans and squash. Both of these techniques add to soil health.”

As the grant enters its third year, the greatest outcome so far, for each of the MILES team members has been relationship building.

One thing I always impart is that we’re always open to visitors, my door is always open and you’re always welcome to stop by. I don’t think you really get to know somebody until you get out and meet them and see how they operate and where they’re at. I think that’s a great step. Mickey Parish

“Up to this point, it’s been more building the relationships between MSU and the other land-grand universities,” said Hart. “Building the relationships so that we know who we could talk to, the resources we could work with, and be able to do networking.”

In addition to relationships between the four land grants in Michigan and learning about each other’s strengths, an important effect has been greater connection with Tribal Nations.

“We’ve seen a tremendous increase in the energy and activity between the land grant system and the Tribal Nations,” Yanni said. “Not that there wasn’t good work that happened before. But I think it’s more focused now and it’s more collaborative now than it’s ever been.”

MSU Extension is also hoping to bring other MSU departments to the MILES table. Christie Poitra, PhD, and director of the MSU Native American Institute (NAI) is the newest member of the team.

“NAI is excited to engage in collaboration with MSU Extension, and expand on our partnerships with tribal communities and tribal colleges,” she said. “Relationships are critical to collaborative work with communities, tribal colleges and Native organizations. It is important to listen to the goals and needs of community partners and co-construct programming. It is also important to develop and maintain relationships over time.”

Relationships are the foundation of everything. And building and investing in relationships takes time.

“We’re an 1862 land-grant university. So we’ve been in existence for 158 years,” Proctor said. “That means we’ve had 158 years with staff, with capacity, with staff funding to do this work with folks beyond the Tribe. It’s time to do this in partnership with, have the patience, do it well, do it in a humble way, and give it time with folks in our Tribal Nations. At least 158 years.”

Future of the MILES Grant Collaboration

In addition to collaborative programming and relationship building, the MILES team hopes to expand programs and capacity in the near future.

“We’ve signed a memorandum of agreement to co-invest in a Tribal health Extension educator to work with four Tribal communities in the Upper Peninsula on very focused Tribal health education needs,” Cudney said. “That’s an example of where we’re working together to share resources and co-invest in Extension educators to assist communities in a very direct and meaningful way.”

Hart at Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College is also hoping that additional staffing will come out of the MILES partnership.

“I’d like to see a person here,” she said. “Because if we had a person here from MSU, working here at the college, then I think it would be easier for us to be able to collaborate and have the same kind of connection that Bay Mills and Keweenaw have with their Extension person.”

At Bay Mills Community College, Parish is enthusiastic about expanding their research and programs in new areas.

“We’d like to see a continued expansion of the research we’ve been doing and some work in other fields,” he said. “The land-grant program has been a great program, but that’s not the only program at MSU. Hopefully by working with the land-grant program and showing the success that we can have, that we will be able to partner in some other areas that will bring new economic opportunities to the Tribal communities.”

Looking into the future, Hadden and Laux hope that this work will increase connections and services to the other Tribes. And Proctor has a vision for what that looks like from MSU’s perspective.

“We need to make sure that what we’re doing is culturally appropriate and it’s based on Indigenous knowledge and what the Tribes need who are already in partnership,” Proctor said. “It also needs to be able to respond when and if the other Tribes are ready to connect. And we need to be humble enough, to have the humility that if we need to change something, we can do it. Also, we have a seat at our administrative table and various tables from this point forward.”

She also hopes that MILES will continue to help MSU Extension statewide staff members understand their role with Tribal communities too.

“It’s empowering our staff that they can work with Tribes,” she said. “It’s similar to other communities. How do you build friendships, how do you build the coworkers and relationships you have here? It’s a similar fashion. We all make mistakes. I don’t have all the answers, just because I’m an Odawa woman. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to try. That doesn’t mean that if I was asked to work in a variety of other communities and populations — Yeah, I’m going to mess up, but that’s not without love, or caring or trying.”

Her call of action is to all of us: we have to do our own work.

When you are working with Tribal Nations and any communities you don’t have a shared experience with — there are different communities, dialects, cultures, traditions, experiences: we all must do our own work. Emily Proctor

Jacques does not call herself a Tribal Extension educator, because she believes that it is a title that belongs to all staff members in Extension.

“We have Tribal people, even if not the Tribal government headquarters, we have Tribal people in every county in Michigan, so if you’re based in a county in Michigan, it’s part of your job to be moving the needle towards parity and engagement,” Jacques said.

The MILES grant is the next step to developing sustainable relationships based on previous partnerships and episodic projects. In addition, MILES is breaking new ground in internal and external change.

“I hope that this also lays the foundation for future work for the federal government when it comes to working with Tribes,” Proctor said. “There’s a history there that’s undeniable, and I have hope. MILES isn’t a project. MILES is a change agent. It’s our next step to making good cultural, organizational systemic change.”

And although the MILES grant funding itself has a timeline, establishing relationships and investing in this new land-grant system doesn’t.

“I want to emphasize that this work needs to continue, and will continue, well beyond whatever grant that helps support the work times out,” Cudney said. “We are just scratching the surface about how we create an inter-tribal land-grant system, and it must be based on trust and it must be based on transparency.”

Print

Print Email

Email