Probing the past informs fisheries management for the future

Add Summary

To effectively manage fish populations, you need to know where fish come from – both literally, and more philosophically.

Andrew Carlson, a PhD student at Michigan State University’s Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability, has published two papers that fill knowledge gaps in understanding the conditions which best nurture and sustain fish populations.

From large reservoirs of the Missouri River to small streams of Minnesota’s Driftless Area, these studies inform and advance management of ecologically, socioeconomically valuable fish and the habitats they live in.

In a paper published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, Carlson, while earning a master’s degree at South Dakota State University, examined tiny pieces of fish anatomy to understand where fish originated. That information can ultimately help fish managers make decisions about broodstock collection, habitat protection and restoration, and harvest regulations.

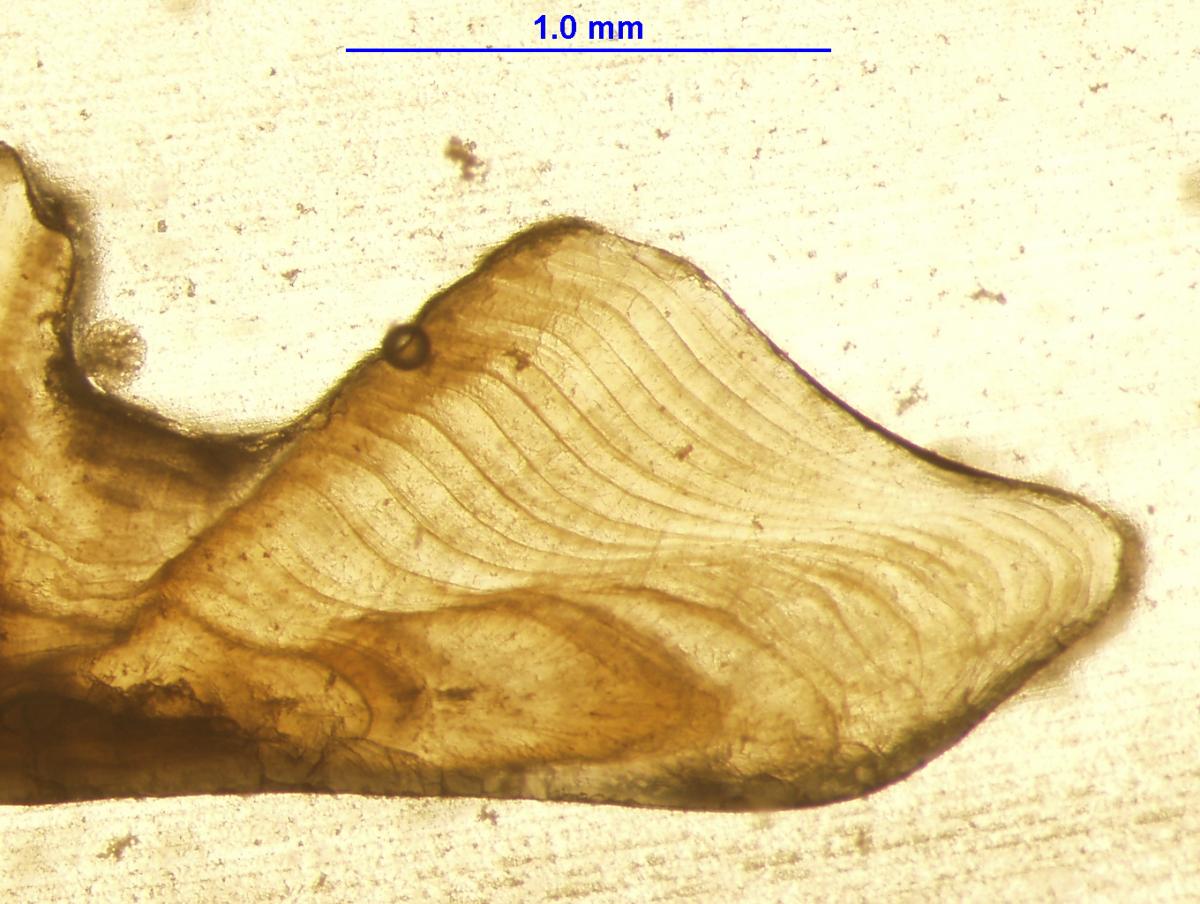

He and his colleagues collected walleye in Missouri River reservoirs in North and South Dakota so they could examine their otoliths -- paired calcified structures used for hearing and balance that form annual growth rings with permanent fingerprints of certain trace elements. Carlson calls otoliths “environmental history tracers” because their chemical composition reflects the environments fish occupy throughout their lives.

examine their otoliths -- paired calcified structures used for hearing and balance that form annual growth rings with permanent fingerprints of certain trace elements. Carlson calls otoliths “environmental history tracers” because their chemical composition reflects the environments fish occupy throughout their lives.

“Walleye are important as a predator fish and support a multi-million dollar fishery in Missouri River reservoirs,” Carlson said. “Prior to this research, otolith chemistry had only been used to assess walleye environmental history in a handful of studies, none of which took place in the Missouri River. Thus, this work helped fill a knowledge gap in walleye otolith chemistry and represented the first application of this tool in Missouri River reservoirs.”

“Otolith microchemistry reveals natal origins of walleyes in Missouri River reservoirs” was also written by M. J. Fincel and B. D. S. Graeb.

Carlson studied brown trout in southeastern Minnesota streams to understand the landscape and local factors affecting trout growth while completing honors thesis research at the University of Minnesota, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology.

The work indicated that growth of brown trout – those one and two years old – is influenced primarily by stream drainage area, a measure of watershed size.

Having forests growing along streambanks is a secondary bonus. Overall, this research advances brown trout management by demonstrating that streams with large, forested watersheds are suitable for management strategies, including habitat restoration and harvest regulations, to increase growth and the abundance of large brown trout.

“Brown trout growth in Minnesota streams as related to landscape and local factors” is published in the Journal of Freshwater Ecology, authored by Carlson and William French, Bruce Vondracek, Leonard Ferrington, Jr., Jane Mazack and Jennifer Cochran-Biederman.

The work in the walleye study was funded by the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station; and South Dakota State University.

The brown trout research was supported by the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund administered by the Legislative Citizens Committee for Minnesota Resources, and the Kalamazoo Valley Chapter of Trout Unlimited.

Print

Print Email

Email