Studying the impact of diversity in all forms

Entomologist Will Wetzel is trying to understand the consequences of environmental variability for plants and insects, as well as how they cope and survive in the face of it.

For as long as he can remember, the diversity of the world has fascinated MSU AgBioResearch entomologist Will Wetzel. Whether he’s contemplating the interactions of millions of plant and insect species, the diversity of individuals within those species or the sheer variety of environmental changes every day, Wetzel has been driven to understand more.

“A big part of my work has been trying to understand the consequences of all that variability for plants and insects, as well as how they cope and survive in the face of it,” said Wetzel, assistant professor in the MSU Department of Entomology. “Personally, I sometimes get overwhelmed by having too many cereal choices at the supermarket, but insects have to deal with far more—thousands of species and genotypes of potential host-plants, a diversity of potential predators and constant environmental fluctuations.”

The agricultural landscape is a constructed environment that often lacks the diversity of species found in natural systems, which reduces farmland’s resistance to damaging insects and forces farmers to rely on insecticides for pest control.

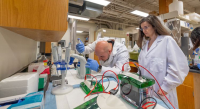

Wetzel said the relatively low levels of insect damage to plants in natural settings suggest there is something about those settings’ diversity that keeps pests in check. He hopes to bring those benefits to farms. In research at MSU’s W. K. Kellogg Biological Station, Wetzel is looking to increase the natural resistance of tomato plants to insects.

Tomatoes naturally protect themselves from pests by several mechanisms, including entangling leaf hairs, toxins and sticky substances that obstruct insect feeding. While conventional tomato plantings usually only feature one combination of these defenses, Wetzel believes that adding a greater variety will increase the resilience of the entire crop.

“We hope to figure out how we can reengineer natural levels of plant defense diversity into cropping systems in a way that will keep pest densities low and prevent pest outbreaks, while limiting our reliance on chemical pesticides,” Wetzel said. “We’re looking for smart ways that are feasible for growers to reincorporate that into the agricultural ecosystem.”

Wetzel’s team is also studying the impact of changing weather and climate conditions on crops and insects. Using open-top chambers capped with heat lamps, they are simulating the effect of extreme heat waves – which are becoming more common as the climate changes – on potatoes, Colorado potato beetles and milkweed plants.

“These extreme heat events are becoming more intense and more frequent, but we have a poorer understanding of them than we do of more gradual climate changes because they’re harder to study,” Wetzel explained. “We’ve developed a method that lets us simulate their effects so we can collect more data on their impact on both agricultural and natural ecosystems.”

The community of researchers at MSU who are dedicated to tackling the many ways plants grow and defend themselves against pests and diseases at all levels, from the molecular to the global, drew Wetzel to the university.

“We have here at MSU an incredible group of people working on these important topics at every level, both in fundamental and applied research,” Wetzel said. “Being able to work with scientists who’ve been studying this subject for decades, and then passing that on to my own students, is incredibly rewarding.”

Q&A: Will Wetzel

Title: Assistant professor of insect ecology, MSU Department of Entomology

Joined MSU: 2016

Education: B.A. in biology and environmental studies, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 2006; Ph.D. in population biology, University of California, Davis, 2015

Hometown: Mamaroneck, New York

Influential or inspiring person: My wife.

On my bucket list: Using ecological theory to make agriculture sustainable.

Favorite vacation: Trekking in Nepal.

On a Saturday afternoon you’ll likely find me: Looking for insects with my toddler, Ellery, who can identify insect damage on leaves with the best of them.

Best part of my job is: Seeing students have “aha!” moments.

If I weren’t a researcher I’d be: A writer.

Something most people don’t know about me: My first love was marine ecology. I loved recreating communities in buckets – seaweed, snails, minnows, crabs – and watching species interactions unfold, especially predation, particularly blue crabs attacking minnows.

Books I’d recommend: For Love of Insects, by Thomas Eisner; A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There, by Aldo Leopold; The Living Mountain, by Nan Shepherd; The Snoring Bird, by Bernd Heinrich; The Snow Leopard, by Peter Matthiessen.

Words of advice to a young scientist: Have fun and make time for thinking.

Favorite food: Brassica oleracea (also known as cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kale, cabbage, broccoli, kohlrabi, collards . . .).

Research breakthrough I’d like to see happen in the next decade: Why do plants produce so, so many different chemical compounds?!

Favorite song or band: Recently Darlingside, but I always come back to Townes Van Zandt.

Person I’d most like to meet, living or dead: Trite but true – Charles Darwin.

Print

Print Email

Email