For a discipline whose chief journal is one hundred years old, the role of an agricultural economist is all-too-often misunderstood. Most of us love to work on multidisciplinary teams, yet sometimes our multidisciplinary colleagues don’t entirely understand what we actually do. This brief blogpost seeks to clarify what skillset you’re asking for when you ask for an agricultural economist to join your team.

#1: We think long and hard about opportunity costs

There is a famous story about Harry Truman that illustrates this point. After asking one of his chief economists about the impacts one of his seminal policy accomplishments, he fumed: “Give me a one-handed Economist. All of my economists say ‘on one hand…,’ but they ALWAYS follow with, ‘but on the other hand…’”

More than anything else, our primary interests lie in evaluating tradeoffs. In economics speak, these are “opportunity costs.” If your son spends all his money on a Snickers bar, that means he has foregone the opportunity of purchasing a Milky Way. The same principle often underlies our thinking when it comes to multidisciplinary projects; if a grower chooses to plant cherry trees on ten acres, he has foregone the opportunity to plan chestnut trees on that same ten acres. When consumers choose to buy steak for dinner tonight, they are foregoing alternative proteins such as chicken.

Those tradeoffs exist throughout the agricultural value chain, meaning that we work on decision-making on-farm, in the grocery store, and everywhere in between. We often prefer to deal in “revealed preferences.” That is, we believe that observing what people do can tell us a lot about what they value. Francis Epplin used to tell a fable to his grad students about a young professor who thought he knew it all. The new professor had run a bunch of models and "discovered" that wheat farmers had been harvesting the wrong way for decades. Elated, he brought his findings to a senior ag economist to get feedback. Heaving the paper across the older economist’s desk, the younger professor began rattling off his findings. Without even glancing at the abstract, the senior economist said, “You’d probably better run a few more models and talk to a few more farmers, because these guys don’t leave dollar bills on the sidewalk. If they’ve been doing it this way for years, there’s probably a reason.”

#2: Yield Maximization is NOT Profit Maximization

#2: Yield Maximization is NOT Profit Maximization

Physical sciences are highly focused on expanding what is technically feasible. Basic science often means exploring what is feasible with what is cost effective as an afterthought. Unfortunately, the world of publishing pushes us to generate “statistically significant” results, which induces “p-hacking” after the experiment has been conducted. While not always true, economists can be unpopular with physical scientists because they often feel like we “shoot them down” after their experiment is done.

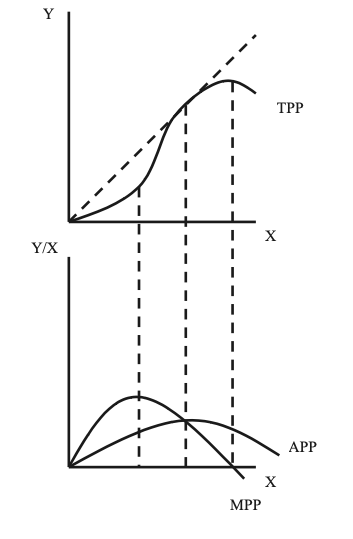

Work by Watson, Hudson, and Segarra (2004) on cotton in the Texas High Plains illustrates this difference. Using precision agriculture techniques, managing to maximize profits resulted in an average 2% higher profits per acre, but yields were 1.2% less. Under whole-field farming, profits were an average 7.2% higher, but yields were approximately the same. Maximizing profit resulted in an average 33% less nitrogen application. The difference lies in something we call the marginal product (and marginal value product).

Once you reach a certain point, each additional unit of input increases output by less, until you reach maximum. Yield maximization aims to reach that maximum point. But, because each unit of input costs the same and each unit of output generates the same revenue, the point at where the difference between revenue and costs is maximum lies to the left of the maximum output point. How far to the left depends on costs and resource constraints, but we know it is virtually never the point of maximum production.

#3: Short-run versus long-run costs and profitability

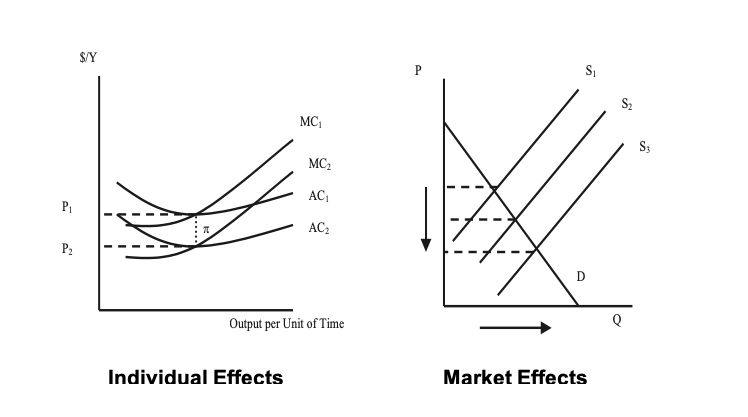

The previous discussion about yield vs. profit max focuses on the short run. In the short run, a new technology or farming technique can increase profits to early adopters, but in the long run, it has no impact on profits. Profits in the long run are zero. This is not accounting profit, this is economic profit, and there is a difference—opportunity costs.

The drive for lower costs to increase short run profits continually puts downward pressure on prices. Being “ahead of the game” requires early adoption—those failing to adopt eventually exit the business.

#4: There are TWO sides to a market

Physical scientists are necessarily focused on the supply side of the market. At times that has the potential to create an “If you build it, they will come” mentality. All too often, our multidisciplinary colleagues utter things like: “Those stupid consumers just don’t realize the GMOs are not bad for them,” under their breath. Economics teaches us that IT DOES NOT MATTER whether consumer preferences are based on incorrect notions. If consumers demand something that is not available, someone will attempt to develop the technology to produce it. If consumers don’t want something, it doesn’t matter how much or how cheaply you produce it, they will not buy it. The price of a product is determined by BOTH the costs of production (resource constraints) and consumer demand (tastes, preferences, income, and availability and prices of substitutes and complements). Ultimately, the Consumer is King. A recent article in Beef Magazine put it best:

“Remember this: every dollar that goes into your pocket when you sell your cattle starts when a consumer decides to buy beef.”

This can make us unpopular when it comes time to writing grant deliverables. Oftentimes, when we talk to hard scientists about what they want to accomplish with a project, they say something like, “We want to increase the number of X growers by Z percent.” This kind of thinking is likely to drive an agricultural economist crazy. Encouraging a large surge of production in any industry is going to send prices plummeting. Goals to increase usage or adoption of your idea are not necessarily in the best interests of growers and their profits. That is OK. It doesn’t mean your idea is bad. It just isn’t for everyone…and, unfortunately for our relationship, it is our job to say so.

Consider the ongoing issue of pine forests in the Southern United States. At the height of the 1980s-era farm crisis, USDA launched the Conservation Reserve Program, which paid farmers annual sums of money for planting trees and grasses. The notion of planting trees, collecting the CRP money, and then harvesting the forests for timber thirty years later as a retirement plan took root. Over the past forty years, the amount of wood growing per acre across most of the South has quadrupled, wiping out retirement savings across the region. By the measure of “increasing the number of X growers by Z percent,” the program was a huge success – but the economics behind the measure has been catastrophic for many growers.

#5: We are NOT cost accountants.

Cost accounting is only a minor part of economic analysis—variable cost is easy, but how do you allocate the cost of a tractor to per bushel cost. Cost of production estimates for your experiments are NOT publishable in economics journals. What we’re more interested in is what those costs of production tell us about the world. Take an extreme case. What if an agronomist really wanted to develop a method to grow pineapples in North Dakota. I could not imagine an economics journal being interested in a simple budget for the cost of production of the North Dakota pineapple alone.

We can contribute A LOT…if you let us

Agricultural economists are social scientists who get lots of encouragement to consider applied problems from multiple perspectives, so we are always thrilled to be involved with unique projects. As Nobel Prize winner F.A. Hayek (1967) said:

“But nobody can be a great economist who is only an economist – and I am even tempted to add that the economist who is only an economist is likely to become a nuisance if not a positive danger.”

We attempt to bridge the gap between the realm of what is possible with what is needed to achieve the objectives of alternative parties. We offer the ability to analyze true costs of production as well as infuse the demand side of the market and other social/policy aspects to your research.

In light of these notions, there are a few takeaway points relevant to developing successful collaborations with your friendly neighborhood ag economist. Bring us in on the front end of your experiments; don’t wait until the end and then ask us what it costs. We do not want to tinker with your experimental designs, but we can identify bottlenecks, infeasibilities, and data needs that can improve subsequent economic analysis and improve your efficiency at obtaining results that are economically feasible.

Print

Print Email

Email