At the beginning of March, MSU Extension hosted their annual Great Lakes Hop and Barley Conference in Traverse City. Researchers provided attendees with high-quality content from across the beer value chain with a focus on the information most useful for Michigan hop and barley growers. The hop industry is expanding especially quickly across the state- you can tour hop yards from Detroit to the Upper Peninsula. In fact, Michigan is the fourth largest hop-producing state in the country and the largest outside of the Pacific Northwest. The quality and consistency of Michigan hops have dramatically improved over the past few years, thanks in part to the industry’s support from key groups such as the Michigan Brewers Guild and Michigan State University.

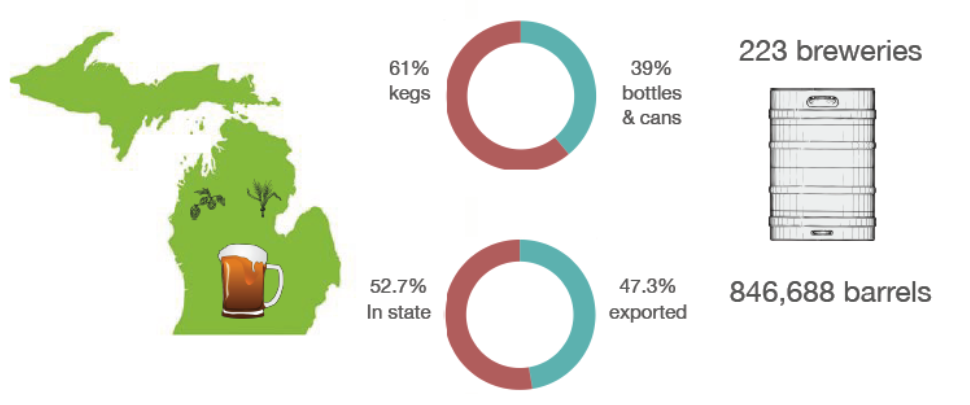

This growth would have never happened without Michigan’s burgeoning craft beer industry. In a recent peer-reviewed journal article funded by an MDARD Value-Added Grant, Steve Miller, Ashley McFarland, Rob Sirrine, Phil Howard, and I estimated the economic impacts of craft beer from the hop yard to the pint glass. Figure 1 displays some key findings. In 2016, 223 Michigan brewers produced an estimated 846,688 barrels of beer. Each barrel is equivalent to 248 pints, meaning that consumers knocked back almost 210 million pints of Michigan beer in 2016! Michigan consumers drank over half of those pints, but almost 100 million pints were shipped across state lines.

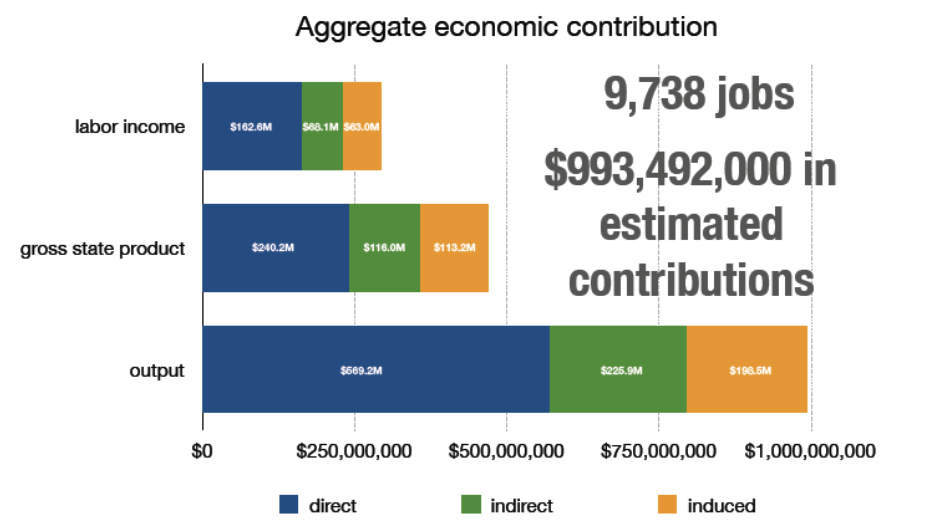

It is important to remember that simply focusing on the volume of beer production overlooks key aspects that make the industry so valuable for Michiganders. Each pint represents a great many economic decisions made by farmers, wholesalers, distributors, and retailers. The dollars those decision-makers spend trickle throughout their local economy. Those purchases can place more dollars in their neighbor’s pocket and can even contribute to increases in employment. As such, it is important to remember that industries not only have a direct effect, but can also generate indirect and induced economic contributions for a state as well. Economists commonly use a method called “input-output analysis” to evaluate the economic contributions of different industries within a regional economy. Figure 2 displays our estimates of these economic contributions for the craft beer value chain in Michigan. The numbers are impressive because of the vertical integration of our beer value chain; many Michigan brewers buy Michigan hops. Our estimates suggest that Michigan’s Gross State Product in 2016 would have been almost $500 million smaller if the state were dry. In total, our estimates suggest that Michigan’s beer value chain contributes almost $1 billion and 10,000 jobs to the regional economy.

To be clear, there are many caveats to these estimates. If there were no beer, maybe we would all just drink cider, liquor, or wine instead. If there were no alcohol, perhaps issues tied to alcohol (domestic violence, drunk driving, etc.) would decrease. But then again, society tried that almost a century ago and failed miserably. The most important lesson to remember is that every economic choice can indirectly generate consequences that often dwarf the choice’s direct effects.

Just because the Michigan hop industry has experienced incredible improvements over the past few years does not mean there is nothing left to explore. The notion of “terroir” represents one of the most exciting new frontiers for the Michigan beer value chain. Developed in the study of wines, terroir implies that the soil, topography, and climate of where an agricultural product was grown will have effects on the taste of that product. The uniqueness of Michigan’s natural environment relative to that of the Pacific Northwest means that there is substantial promise for generating “buzz” in the craft beer world about flavor profiles that can only be generated by Michigan-grown inputs. Indeed, many in the craft beer community across the country have acknowledged that this is in fact the case. To highlight these unique flavor profiles, this year’s Great Lakes Hop and Barley Conference marked the second annual Chinook Cup, where growers competed to take home an incredible traveling trophy awarded for their ability to grow the Chinook cultivar at a premier level.

Those of us here in MSU’s Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics are eager to collaborate with the industry to further explore this concept. In collaboration with the Michigan Brewers Guild and MSU Extension, Vincenzina Caputo and I recently completed the data collection of a brewer survey where we asked about their opinions and perceptions of Michigan hops. The results were promising, as many brewers expressed enthusiasm about the current direction of the hop industry. To capitalize on these findings, the Hop Growers of Michigan conducted a blind taste test at the Great Lakes Hop and Barley Conference where Ludington Bay Brewery brewed two of their IPA’s: one with Michigan Chinook hops and one with Washington Chinook hops. Attendees at the conference tasted both and provided their sensory feedback for the two beers. Results suggested that there was in fact a difference in taste between the two beers, and that many of the attendees actually preferred the Michigan-hopped brew. Moving forward, studies such as these are likely to continue increasing the total economic contributions of this burgeoning industry.

Print

Print Email

Email