Michigan chestnut pest report the week of June 1, 2023

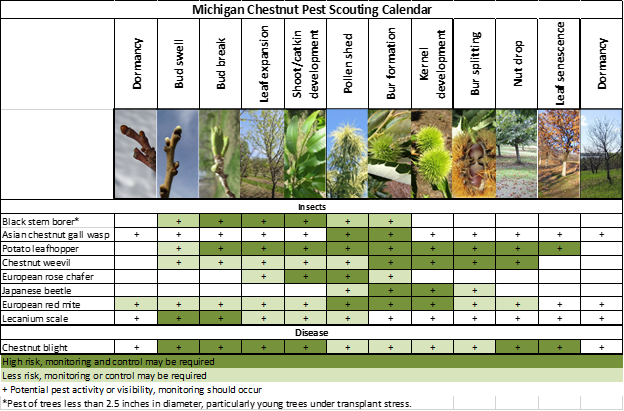

Growers may need to continue to protect against black stem borer. There are a lot of chestnut pests expected to arrive in early June.

For a chestnut production update from around the state, please see the June 1 Chestnut Crop Report.

Insect pests

Lecanium scale activity may be noticeable at this time. Lecanium scale is a soft scale pest that attaches to and feeds on many deciduous plants in Michigan, most notably hardwood trees. Lecanium scale populations can build to extremely high levels over a series of favorable years before crashing due to natural enemies and disease. When present in low numbers, lecanium scale are often overlooked and are of little economic or aesthetic significance.

Check chestnut branches for evidence of this pest. Scales may look a lot like leaf scars or bud scales, so a close inspection is important. Some infestations have only a few scales per branch while others are well-covered. One tell-tale sign of scale activity is the shiny film of honeydew that the scales excrete onto surfaces beneath the scales. Increased ant activity is also associated with scale insects as they collect the honeydew.

The honeydew from scale can act as a substrate for sooty mold. On agricultural crops, sooty mold can become an issue when it ends up on the fruit or nut being produced. Additionally, the scales removes sap when feeding which can weaken shoots and even cause shoot death in some cases. The rule of thumb is that vigorous and healthy trees and plants can tolerate some scale infestation, but if high populations of Lecanium scale are found, control programs should be considered, particularly on small trees. Ideal control windows occur in early spring when buds are dormant and again in July when scale crawlers hatch.

Take our feedback survey on MSU Extension news articles

Your feedback on this article provides critical guidance and support to the MSU Extension Integrated Pest Management Program.

For more information on lecanium scale management, refer to the Michigan State University Extension article, “Lecanium scale numbers building on chestnut.”

Potato leafhopper are arriving in Michigan. Like many plants, chestnuts are sensitive to the saliva of potato leafhopper, which is injected by the insect while feeding. Damage to leaf tissue can cause reduced photosynthesis, which can impact production and quality and damage the tree. Most injury occurs on new tissue on shoot terminals with potato leafhopper feeding near the edges of the leaves using piercing-sucking mouthparts. Symptoms of feeding appear as whitish dots arranged in triangular shapes near the edges. Heavily damaged leaves are cupped with brown and yellowed edges and eventually drop from the tree. Severely infested shoots produce small, bunched leaves with reduced photosynthetic capacity.

.jpg)

Adult leafhoppers are pale to bright green and about 1/8 inch long. Adults are easily noticeable, jumping, flying or running when agitated. The nymphs (immature leafhoppers) are pale green and have no wings but are very similar in form to the adults. Potato leafhopper move in all directions when disturbed, unlike some leafhoppers which have a distinct pattern of movement. The potato leafhopper can’t survive Michigan’s winter and survives in the Gulf States until adults migrate north in the spring on storm systems.

Scouting should be performed weekly as soon as leaf tissue is present to ensure early detection and prevent injury. More frequent spot checks should be done following rainstorms which carry the first populations north. For every acre of orchard, select 5 trees to examine and inspect the leaves on 3 shoots per tree (15 shoots per acre). The easiest way to observe potato leafhopper is by flipping the shoots or leaves over and looking for adults and nymphs on the underside of leaves. Pay special attention to succulent new leaves on the terminals of branches.

For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of potato leafhopper refer to the 2023 Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

Rose chafer emergence typically begins around this time. Rose chafer are considered a generalist pest and affect many crops, particularly those found on or near sandy soils or grassy areas. The adult beetles feed heavily on foliage and blossom parts of numerous horticultural crops in Michigan and can cause significant damage to chestnut orchards. Rose chafer can be particularly damaging on young trees with limited leaf area. Rose chafer skeletonize the chestnut leaves but tend to consume larger pockets of tissue.

Rose chafer are often found in mating pairs and fly during daylight hours. Visual observation while walking a transect is the best method for locating them. Because of their aggregating behavior, they tend to be found in larger groups and are typically relatively easy to spot. There are no established treatment thresholds or data on how much damage a healthy chestnut tree can sustain from rose chafer, but growers should consider that well-established and vigorous orchards will likely not require complete control. Younger orchards with limited leaf area will need to be managed more aggressively.

The rose chafer is a light tan beetle with a darker brown head and long legs and is about 12 mm long. There is one generation per year. Adults emerge from the ground during late May or June and live for three to four weeks. Females lay groups of eggs just below the surface in grassy areas of sandy, well-drained soils. The larvae (grubs) spend the winter underground, move up in the soil to feed on grass roots and then pupate in the spring. A few weeks later, they emerge from the soil and disperse by flight. Male beetles are attracted to females and congregate on plants to mate and feed. For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of rose chafer refer to the 2023 Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

Growers should be keeping young trees protected from black stem borer as long as adults continue to be trapped on site. Black stem borer will infest and damage a wide variety of woody plant species, including chestnuts. Black stem borers are attracted to small trees with less than a 4-inch trunk diameter and stressed trees that produce ethanol. Female borers create tunnels in trunks to lay their eggs. These tunnels damage the tree’s ability to translocate water and nutrients.

Overwintering adults become active in late April or early May after one or two consecutive days of 68 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, often coinciding with blooming forsythia. Adult black stem borers are very small (0.08 inches long).

Growers are encouraged to use a simple ethanol baited trap to monitor for activity starting in mid-April. Traps are most effectively deployed near adjacent wooded areas at a height of 1.6 feet. Hand sanitizer is an easy and accessible bait but should be refreshed every few days. Traps can consist of just a pop bottle (or similar container) with around a 0.5-1 cup of hand sanitizer.

Growers with small, vulnerable trees and positive trap catches or a history of damage will need to apply a trunk spray to prevent damage. The time to spray an insecticide for this pest is when females are flying in the spring before colonizing new trees. Young trees near the perimeter of orchards, especially near woodlots, are at greatest risk of injury. Because they are so tiny, it is impossible to visually monitor for adults to determine the optimum time to apply an insecticide, so trapping as described above is recommended to detect adult activity and apply treatment.

Pyrethroid insecticides applied as trunk sprays have shown the most promise in reducing the number of new infestations within a season. For a list of registered pyrethroids for use in Michigan chestnuts, refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

Later in the season, remove and burn any damaged dead or dying trees. It is also important to make sure all large prunings and brush piles are either burned, or chipped and composted as they may harbor overwintering adults and contribute to future infestations. For more information on black stem borer, refer to the Michigan State University Extension bulletin, “Managing Black Stem Borer in Michigan Tree Fruits.”

In 2022, some growers reported higher than typical European red mite populations. European red mites overwinter as eggs in bark crevices and bud scales and are the most commonly observed species in Michigan chestnut orchards. Eggs are small spheres, about the size of the head of a pin with a single stipe or hair that protrudes from the top (this is not always visible). Eggs can be viewed with a hand lens or the naked eye once you have established what you are looking for.

.jpg)

Scout for overwintering eggs and early nymph activity in the spring to assess population levels in the coming season. As temperatures warm, overwintering eggs hatch and nymphs move onto the emerging leaves and start feeding. Adult European red mite are red in color and have hairs that give them a spikey appearance. Adult and nymph feeding occurs primarily on the upper surface of the leaves. This first generation is the slowest of the season and typically takes a full three weeks to develop and reproduce. This slow development is due to the direct link between temperature and mite development. Summer generations, favored by the hot and dry weather, can complete their lifecycles much faster with as little as 10 days between generations under ideal conditions.

As you scout, remember that not all mites are bad. Consider documenting the levels of predacious mites in your orchard. If healthy populations of mite predators exist, they will continue to feed on plant parasitic eggs and nymphs and can be an effective component of your mite management program. Predaceous mites are smaller than adult European red mite and twospotted spider mite, but they can be seen with a hand lens and typically move very quickly across leaf surfaces.

Mite control starts with monitoring early in the spring looking for the overwintering eggs (European red mite) and assessing the mite pressure. Ideally, growers will be using limited insecticides with miticidal activity in their season long programs, as that protects their beneficial mite populations which help minimize pest mites. If pest mite populations are high enough to require control, superior oil application when the trees are dormant is an effective method of treatment. If issues with mites arise during the growing season, refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide for control options.

Disease

Existing chestnut blight infections (caused by Cryphonectria parasitica) can be observed. There are no commercially available treatments for chestnut blight. Growers may prune out infected branches or cull whole trees as needed to limit disease pressure. Infested material should be burned or buried to further limit inoculum spread. To learn more about chestnut blight, visit the pest management section of the chestnut webpage.

During the 2022 growing season, the causal agent of oak wilt (Bretziella fagacearum) was cultured out of a chestnut tree in an orchard with multiple, established chestnut trees exhibiting symptoms of wilt and dying. As leaves expand in orchards around the state, growers may see trees with wilt-like symptoms. While there are many causes of wilt symptoms in chestnuts (drought, winter injury, phytophthora, armillaria, chestnut blight), consider the possibility of oak wilt as well. To learn more about this issue, refer to the MSU Extension article, "MSU investigating oak wilt as the cause of sudden chestnut tree decline."

Stay connected

For more information on chestnut production, visit www.chestnuts.msu.edu, sign up to receive our newsletter and join us for the free 2023 MSU Chestnut Growers Chat Series.

If you are unsure of what is causing symptoms in the field, you can submit a sample to MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics. Visit the webpage for specific information about how to collect, package, ship and image plant samples for diagnosis. If you have any doubt about what or how to collect a good sample, please contact the lab at 517-432-0988 or pestid@msu.edu.

Become a licensed pesticide applicator

All growers utilizing pesticide can benefit from getting their license, even if not legally required. Understanding pesticides and the associated regulations can help growers protect themselves, others, and the environment. Michigan pesticide applicator licenses are administered by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. You can read all about the process by visiting the Pesticide FAQ webpage. Michigan State University offers a number of resources to assist people pursuing their license, including an online study/continuing educational course and study manuals.

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant no 2021-70006-35450] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email