This Halloween, zombies are not the only beings rising from the soil to haunt the living. In corn and soybean fields across the country, zombie-like weeds that once were easily killed by glyphosate (commonly marketed as Roundup®) are bouncing back. These glyphosate-resistant weeds threaten the benefits that Roundup Ready® and other glyphosate-based weed control systems have long provided farmers.

For crops engineered to tolerate glyphosate, the herbicide offers broad spectrum weed control. Glyphosate-based control systems often reduce grower costs, even after accounting for premiums that growers pay for herbicide-resistant seed. Growers find glyphosate simple and effective. It kills nearly all weed species with a single product that can be applied throughout the growing season. Growers who pair glyphosate with tolerant crop seed save time and fuel costs by taking fewer field passes with lighter equipment. By replacing tillage and more harmful herbicides, glyphosate has allowed many growers to conserve soil, build soil carbon, and reduce wildlife exposure to more harmful herbicides.

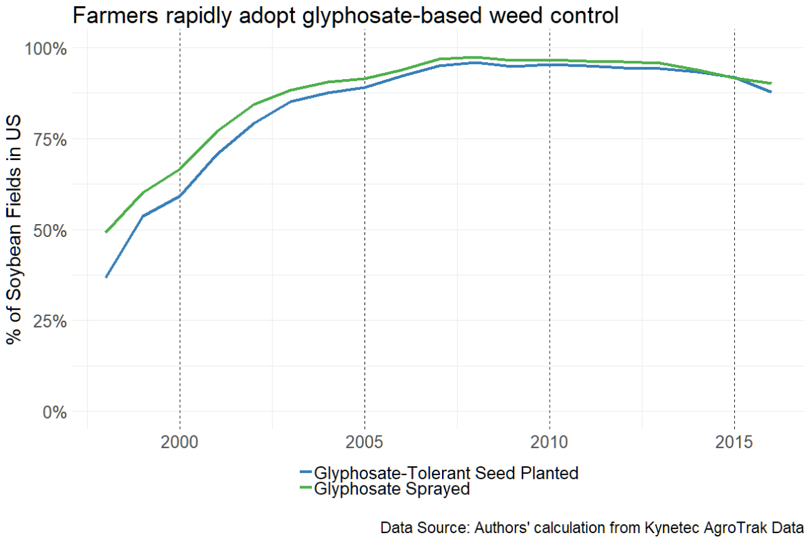

These benefits have made glyphosate wildly popular, as shown in Figure 1. Over 90% of U.S. soybean farmers use glyphosate with tolerant crop seed. Glyphosate-tolerant soybean varieties were first made commercially available in 1996. Since then, glyphosate has gone from popular to pervasive.

Figure 1. Adoption of Glyphosate tolerant seed and glyphosate use in U.S. soybean fields, 1998-2016.

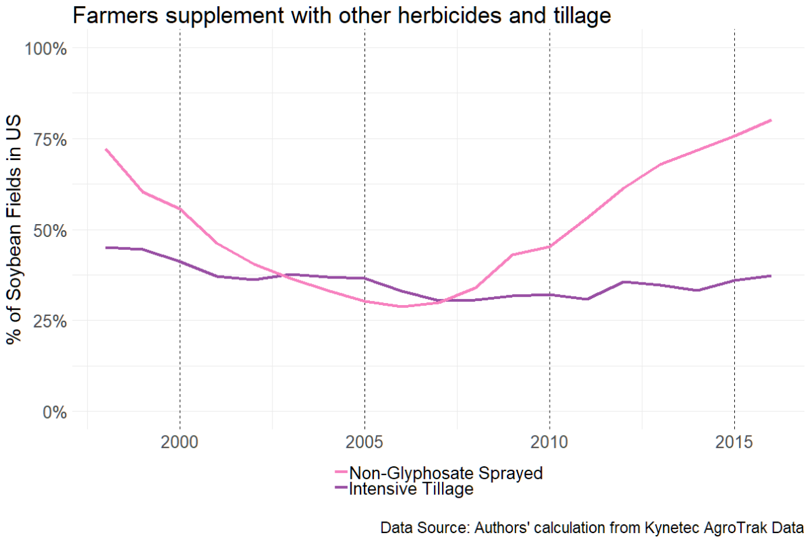

By 2005, farmers nationwide planted glyphosate-tolerant seed on 89% and sprayed glyphosate on 91% of soybean fields. As soybean farmers used more glyphosate from 1998 through 2005, they cut back on other herbicides. Figure 2 shows that use of soybean herbicides other than glyphosate fell from

72% of fields to 30% of fields during the 1998-2005 period (72% to 33% in Michigan). Farmers also trimmed their use of intensive tillage.

Figure 2. Non-glyphosate approaches to managing weeds in U.S. soybean fields, 1997-2016.

But too much glyphosate led to weeds that keep coming back in zombie-like fashion. When sprayed repeatedly with a herbicide with the same biochemical mode-of-action, many weeds evolved herbicide resistance. When only glyphosate is applied every year, there is no back-up silver bullet to take down the lucky weeds that survive. Those lucky survivors then pass their genes on to the next generation. Wind can carry weed pollen and seeds far and wide, allowing these weeds to colonize new fields.

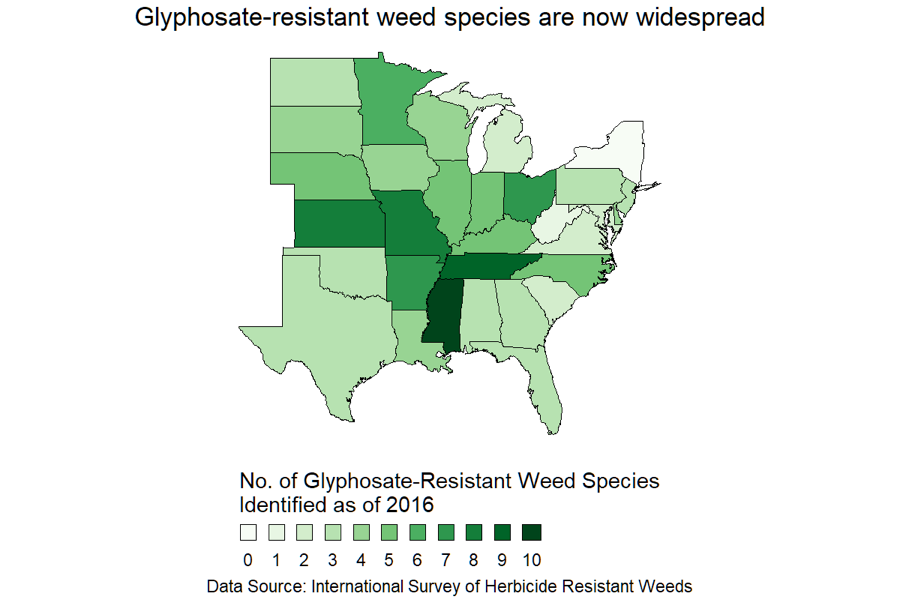

Weeds resistant to glyphosate have spread fastest in the South. Selection pressure has been greatest where farmers grow two glyphosate-tolerant crops per year. The map of glyphosate-resistant weeds in Figure 3 shows the worst infestations in the Mississippi Delta, where cotton and soybean are double-cropped. All this has happened in the 24 years since glyphosate-tolerant soybean seeds were introduced in 1996. By 2016, Michigan had glyphosate-resistant populations of both Palmer amaranth and horseweed.

Figure 3: Weed species with confirmed glyphosate-resistant populations in the Eastern United States, 2016.

Soybean growers have responded to glyphosate-resistant weeds by adding herbicides, tillage, or both. From 2006 to 2016, the use of herbicides other than glyphosate rose from 29% to 80% of soybean fields. Meanwhile, the use of intensive tillage has slowly begun to rise again (see Figure 2).

The newest soybean varieties tolerate both glyphosate and certain other herbicides, such as dicamba and 2,4-D. These give growers added weapons to manage glyphosate-resistance via multiple biochemical modes of action. At the same time, these technologies maintain the simplicity and flexibility of glyphosate-based systems. Unfortunately, they cost more too. Worse yet, Palmer amaranth has already evolved to resist both 2,4-D and dicamba in Kansas—a warning bell for the rest of the nation.

The hidden cost of herbicide resistant weeds hits the environment as well as the farmer’s wallet. Alternative herbicides can damage non-target crops and hedgerows. More tillage means more soil erosion.

Herbicide resistance is hardly new. Michigan farmers counted 12 atrazine resistant weeds by 2004. But glyphosate-tolerant crops offered a fresh alternative to atrazine. Facing today’s glyphosate-resistant weeds, can farmers count on a new herbicide solution around the corner?

Although chemical companies are renewing investment in herbicide research, farmers’ best choice is to do all they can to delay the evolution and spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds. Weed scientists recommend rotating glyphosate with other herbicides and mechanical weed control. These tactics may sound costly, but as the old saying goes, “a stitch in time saves nine.” Investing money and effort today can delay, and perhaps prevent, future herbicide-resistance problems. But mixed weed control is a group effort; even the most diligent grower may fail if neighbors are not equally careful in preventing weeds from evolving to resist herbicides.

How to make sure that everyone pulls together to prevent the spread of herbicide resistance? The tactics that have delayed insect resistance to Bt corn offer one clue. Seed companies, farmer organizations, and the Environmental Protection Agency jointly created a national management plan to prevent insects from evolving to resist Bt. The plan included area refuges and seed mixes that included some non-Bt seeds to slow evolution of Bt resistant insects. Although Bt resistance among insects has developed, it took longer to materialize than many experts had feared. Farmers need a similar strategy for working together to slow the spread of herbicide-resistant zombie weeds

Print

Print Email

Email