Who Was in the Room and How Were They Impacted? The Reach and Value of CRFS Events 2016-2018

DOWNLOADMarch 21, 2019 - Lilly Fink Shapiro, Lesli Hoey, Kathryn Colasanti

Networks are a valuable asset for advancing social change. The Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems (CRFS) coordinates four networks designed to help Michigan’s communities, businesses, and institutions build a healthy, green, fair, and affordable food system:

- the Michigan Farm to Institution Network,

- the Michigan Food Hub Network,

- the Michigan Meat Network,

- and the Michigan Local Food Council Network.

CRFS also hosts a biennial statewide Michigan Good Food Summit to bring people together around the goals of the Michigan Good Food Charter.

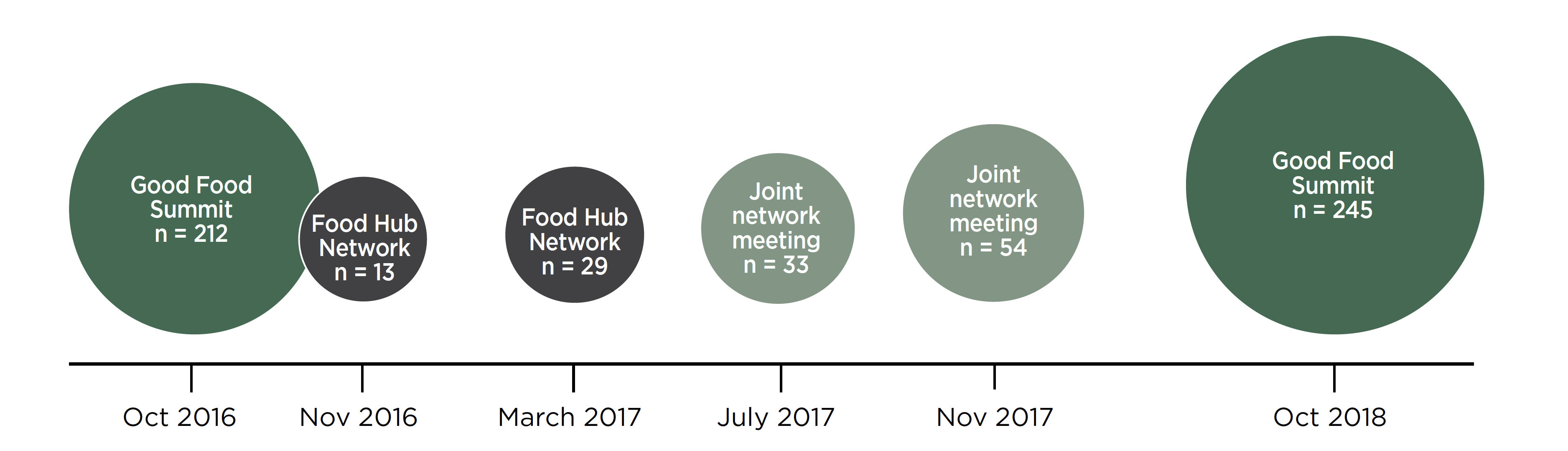

This report uses 586 evaluations collected from 2016 to 2018 to begin to answer questions like, "What motivates people to attend CRFS network convenings?" and "How are summits and network meetings impacting participants?"

This report represents 6 events and 586 evaluation responses.

Who is participating?

To understand who is participating in Good Food Summits, Food Hub Network meetings, and joint network events, we asked participants which networks they are actively involved with, their professional affiliations, and demographics.

Registration data shows that these events collectively engaged people from 150 different cities in Michigan. Outside of Michigan, people from 10 other states and two other countries (Canada and Kenya) registered for one or more of these events.

Network membership status

Since all of the events we analyzed were hosted by CRFS, we expected that the majority of participants would identify as active members of CRFS-led networks. We found, however, that 58% were not part of a CRFS-led network. This included 36% who were not part of any food systems network and 22% who were affiliated with a Michigan-based food systems network that is not facilitated by CRFS (e.g., Michigan Food and Farming Systems, Michigan Farmers Market Association). Approximately 32% of participants, on average, were members of multiple networks and approximately 27% of participants were members of a single network.

Most participants were not affiliated with a CRFS-led network.

| Affiliation | Percent |

|---|---|

| CRFS-led network | 42 |

| No network | 36 |

| Non-CRFS network | 22 |

The 2016 and 2018 Good Food Summits and the July 2017 joint network meeting attracted the most people who were not affiliated with a network (42%, 38%, and 45% respectively). By contrast, most participants in the two Food Hub Network meetings – 11 out of the 13 participants from the 2016 meeting and 21 out of 29 participants from the 2017 meeting – were part of CRFS-facilitated networks. Network membership of attendees at the joint network meetings was inconsistent. Only 39% of participants at the July 2017 meeting were part of a CRFS-led network, compared to 73% of people at the November 2017 meeting. The 2016 and 2018 Good Food Summits attracted the smallest portion of people who indicated membership in multiple food-system networks, with 25% and 29% of participants respectively. The Food Hub Network meetings had the smallest number of participants but the largest portion of people who indicated membership in multiple networks, with 55% - 62% of participants.

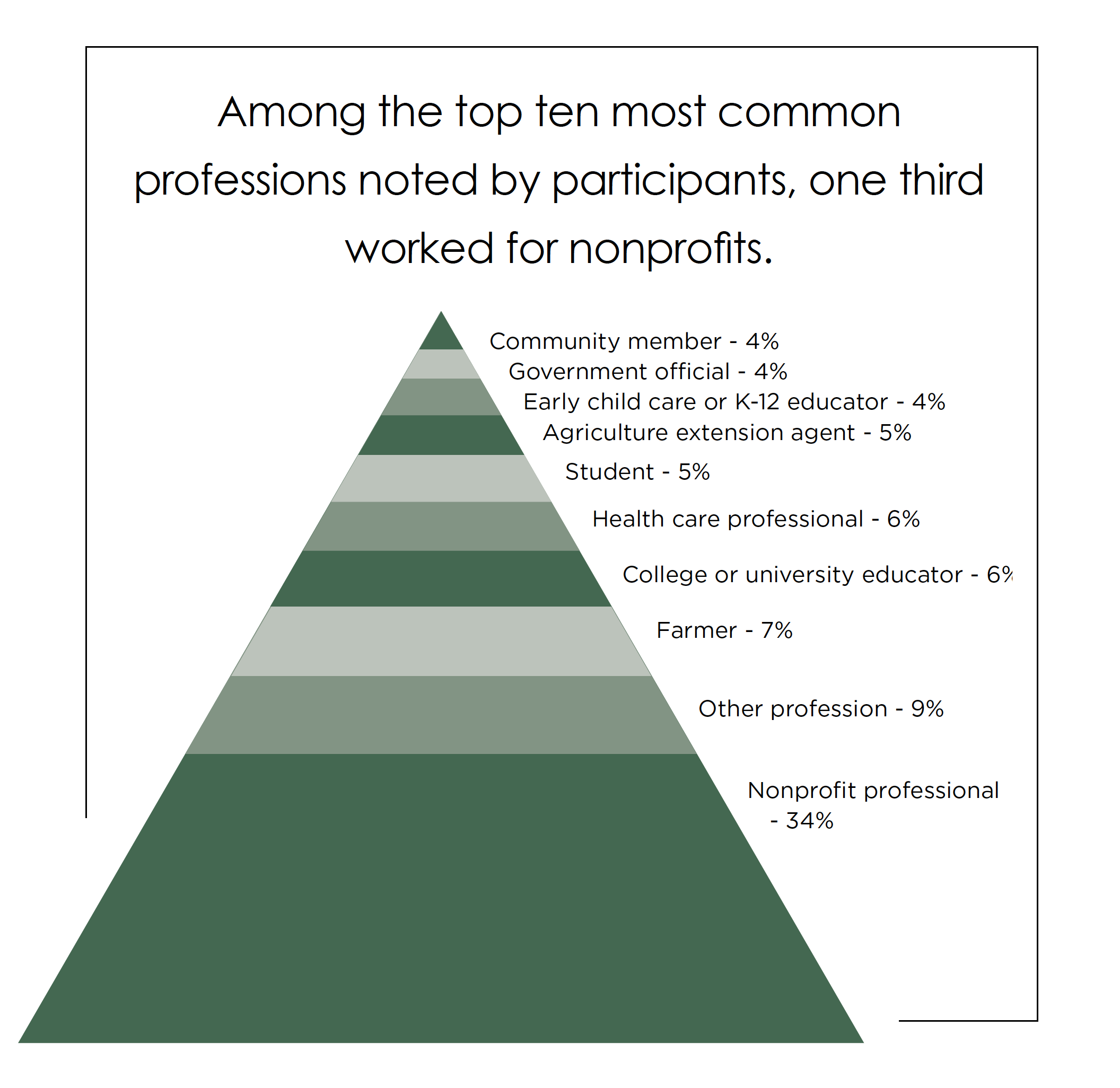

Professional affiliations and demographics

Nonprofit professionals were the highest percentage of attendees across all events, composing 35% of participants, on average. The three events with the highest percentage of nonprofit professionals were the 2018 Good Food Summit (40%), 2017 Food Hub Network meeting (39%), and 2016 Good Food Summit (34%).

The July 2017 joint network meeting was unusual in so far as it attracted a high percentage of people who did not identify with the listed job categories (24%), as well as relatively high percentages of growers, farmers, and producers (12%) and government officials (12%).

The 2016 Food Hub Network meeting also attracted a high percentage of college or university educators (15%) and a similar percentage of growers, farmers, and producers (15%). The November 2017 joint network meeting attracted many agriculture extension agents (13%) as well as a high percentage of people who did not identify with the provided categories (16%).

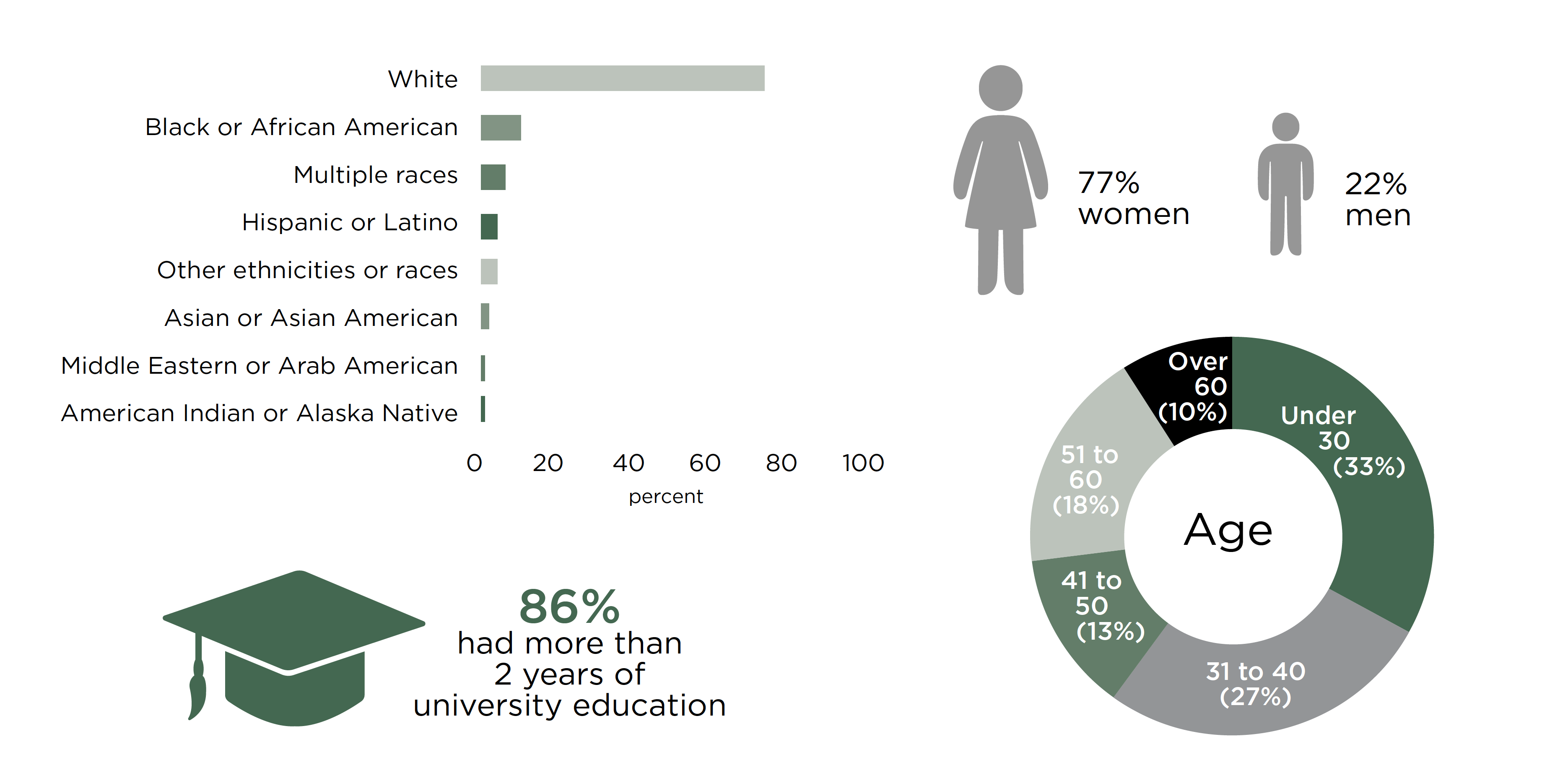

Demographics varied by event, but participants tended to be white women with a university degree and under the age of 40.

Most participants across all events identified as female (77%); 22% identified as male and 1% as nonbinary or preferred to self-describe. The 2016 Food Hub Network meeting and July 2017 joint network meeting were the most gender balanced, each with 39% of participants identifying as male.

Over half of participants (58%), on average, were under 40 years old. The two Good Food Summits and July 2017 joint network meeting attracted a particularly high percentage of 21 to 30 year-olds (31% to 35%). Both Food Hub Network meetings and joint meetings attracted a particularly high percentage of people between 51 and 60 years old (20% to 33%).

On average, 74% of participants identified as White, composing between 73% and 92% of attendees across all meetings. The largest percentage of people of color (between 4% to 14% across meetings) identified as Black or African American. The two Good Food Summits attracted the most racially/ethnically diverse makeup of attendees, with people of color making up 27% of the 2016 Summit (n = 55) and 23% of the 2018 Summit (n = 53). Participants across all events also tended to be highly educated. Approximately 84% indicated a bachelor’s degree or a graduate/professional degree as their highest level of education.

Why are they participating?

On average, nearly three quarters of participants attended the events to learn about what others are doing in the local food movement (74%) and to network (70%). Learning about what others are doing was a particularly clear goal for participants of the two Good Food Summits (80% of attendees from the 2016 Good Food Summit and 73% from the 2018 Good Food Summit), as well as the 2017 Food Hub Network meeting (79%). Networking was an especially strong motivating factor for people who attended the two Food Hub Network meetings and the July 2017 joint meeting (noted by 85% to 92% of participants). But networking motivated a somewhat smaller percentage of people at the November 2017 joint meeting (74%) and the 2016 Good Food Summit (76%) and a substantially smaller percentage of people the 2018 Good Food Summit (58%).

Just over half of participants (55%), on average, attended the events to represent their business or organization. Learning about resources was noted, on average, by half of participants (50%). The 2016 Good Food Summit was an exception: 79% of participants saw this as a key reason to attend. The smallest percentage of people attended each of these events to learn new skills, though this still accounted for 28% of participants in both Good Food Summits and 21% of attendees of the 2017 Food Hub Network meeting.

Most people came to learn what others are doing in the local food movement and to network.

| Reasons for attending | Percent |

|---|---|

| Learn what others are doing | 74 |

| Network | 70 |

| Represent my organization | 55 |

| Learn about resources | 50 |

| Learn new skills | 24 |

How are participants impacted?

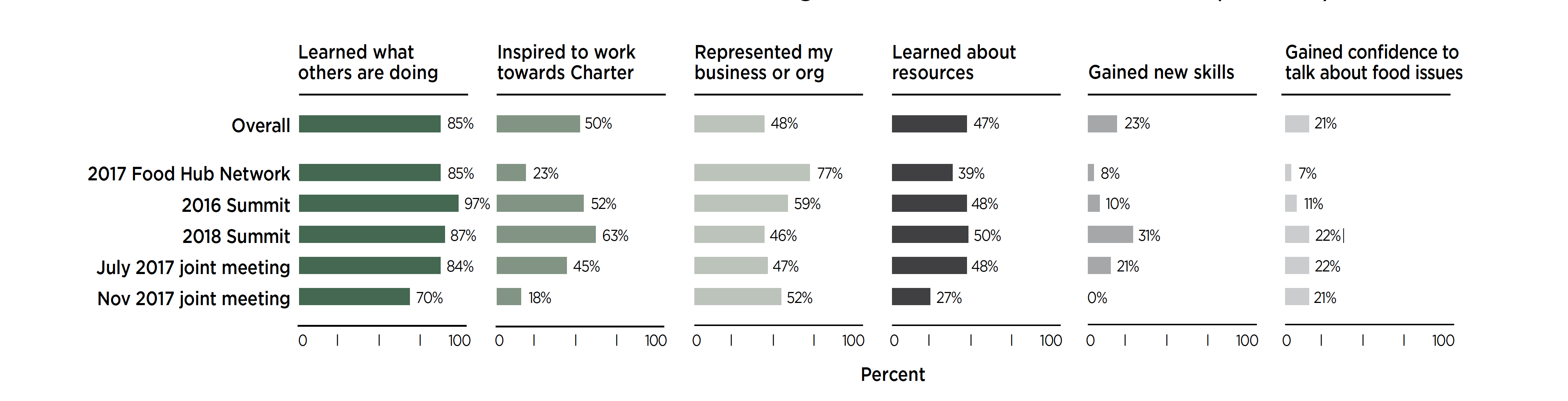

In line with their reasons for attending, 70% to 97% of attendees across all the events indicated that they learned about what others are doing in the local food system. On average, about half of participants also reported other types of impacts. More participants in the two Good Food Summits (63% at the 2016 Good Food Summit and 45% at the 2018 Good Food Summit) and the 2017 Food Hub Network meeting (52%) were inspired to work with others towards one or more goals of the Michigan Good Food Charter. Compared to other events, a higher percentage of people at the 2016 Food Hub Network meeting also noted that they were able to represent their business or organization (77%). Approximately one fifth of participants, on average, indicated learning new skills (23%), especially at both Good Food Summits (31% at the 2016 Good Food Summit and 21% of attendees at the 2018 Good Food Summit). A fifth of participants (approximately 22%) at both Good Food Summits and the July 2017 Food Hub Network meeting indicated that they gained confidence in their ability to talk about food issues. Across all events, only 3% of attendees indicated that the event had no impact on them.

All events also helped participants to network with new and existing contacts. On a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being “strongly agree,” participants, on average, rated the events from 4.0 to 4.5 when asked if they planned to contact at least one new person they had met. When asked if the event helped them strengthen an existing relationship with a colleague, participants rated the events 3.9 to 4.6 on average. They rated the 2016 Food Hub Network meeting highest in both cases, a 4.5 for helping them make new connections and a 4.6 for helping them reconnect.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings show that CRFS-hosted networking events over the last three years have brought diverse people together and provided clear value. The Michigan Good Food Summits, Michigan Food Hub Network meetings, and joint network meetings attracted members of CRFS-facilitated networks. Even more, they drew people who are part of other Michigan food systems networks or who are not currently participating in food system networks.

The number of participants from outside of CRFS networks shows the value of these events in broadening engagement and facilitating new connections. Furthermore, by attracting people from a range of different networks and people with multiple network memberships, these events appear to be both serving to build bridges – creating cross-network linkages – and attracting bridge builders – people with connections to multiple networks.

Regardless of their profession, demographics, and network membership, the majority of participants walked away from these events having accomplished what they had hoped to get out of the meetings: learning about what others are doing in the local food system, establishing new contacts with potential to develop into new collaborations, and strengthening relationships with their existing food systems contacts.

Differences that emerged between the Good Food Summits and network events emphasize the value of offering diverse meeting formats – from more open-ended, less structured events to more topically-focused formats – for people to meet and learn from one another as they collectively work to strengthen Michigan’s food system.

Download the PDF version below!

Print

Print Email

Email