Faces of the Network Podcast #2: Abbey Palmer, Community Food Systems Educator, MSU Extension

Author: Zaire Parrotte, Abbey Palmer, Colleen MattsHosted by Farm to Institution Data Manager Zaire Parrotte, the Faces of the Network Podcast is a space to hear stories from Michigan champions, partners, and supporters who are leading the way in supplying, sourcing, and serving Michigan food, from the farm to the institution. This series is brought to you by the Michigan Farm to Institution Network. In this second episode, we meet Abbey Palmer, Community Food Systems Educator for Michigan State University Extension.

June 26, 2022

“[What] really gets me excited is inclusivity, when everyone in the institution and in the community feels like they get to have part of the experience of local food." Abbey Palmer

Transcript

Zaire Parrotte: Welcome to the second episode of Faces of the Network. This series is brought to you by the Michigan Farm to Institution Network (MFIN), which is coordinated by the Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems and MSU Extension. My name is Zaire Parrotte, and I am the Farm to Institution Data Manager.

In this series, we will hear stories from Michigan champions, partners, and supporters who are leading the way in supplying, sourcing, and serving Michigan food, from the farm to the institution. In this episode, we will get to learn about Abbey Palmer. She is part of the MFIN Management Team. I asked her a few questions and asked at the end if she had any final thoughts of her own.

What is your role in farm to institution work? How long have you been doing this work?

Abbey Palmer: Well, I started learning about food systems after I got done with a Creative Writing Master's Degree. I came back to the Upper Peninsula in 2010 and was adjuncting and teaching creative writing and literature, but I got a part-time job at the Marquette Food Co-op, and I started learning about food systems and getting more into the local food movement at that time. I've worked for Michigan State University since 2015 and have worked for MSU Extension since 2019. I joined the MFIN Management Team in 2020, but it might have been late in the year.

My role in farm to institution work is primarily focused on a part of farm to school. I do a lot of K-12 education where I get to work with students in their classrooms, on their school garden projects, or connecting them with food safety resources so that when they harvest their lettuce and they're going to take it and eat it in their consumer science class, they know all the steps. But a larger part of my work with farm to institution is actually training teachers - K-12, college, or K-14 teachers - how they can incorporate more agriculture and food systems into what they teach. I can talk more about specific projects later, but I think of myself as a connector between some of the farms in my area and the schools for the purpose of learning more about where food comes from.

Zaire Parrotte: Wow, that's really cool! You were in creative writing. Are there opportunities where you're able to apply that creative writing into your farm to school at work?

Abbey Palmer: There was someone who said, “The writer is the person on whom nothing is lost.” I think that comes into play for me when I meet all of the different people who are involved in the food systems work – all of the different characters, all of the different individuals - everyone has their story when it comes to why their school looks the way it does, why their school garden looks the way it does, why their farm looks the way it does, and why any of these people want to talk to each other. Everybody has a narrative. There's a reason that they are able to do this work and take the time for it. That's definitely where the writer in me comes out. When it comes to writing those grants – do that grant reporting - I’m not a journalist or anything, but the writing skills come in handy for those parts of the job. I'm not working on a novel about Upper Peninsula farmers, but I'm definitely gathering material for when I retire and have time to write more.

Zaire Parrotte: That’s so awesome! That's a really good perspective on seeing how every person in every institution has a story or a narrative to tell, especially within the food system and how it impacts them. MFIN is a big story too. That’s what the Faces of the Network is - stories. That’s a really cool perspective.

What is most exciting to you about your farm to institution work?

Abbey Palmer: There are a few things that really get me fired up. One is getting outside with kids. When youth get outside to learn about agriculture and food systems, it's always a memorable experience. Whether we're going to the school garden or we're visiting the farm where I work - the MSU Upper Peninsula Research and Extension Center - or were visiting another farm or a farmer's market, I know that I'm with people who are going to remember what we did that day because it brought them outdoors into a different sensory environment. Just giving a chance to carry out some of those activities together and being in community with people is very exciting. I love also the little steps toward the bigger goals. In the Upper Peninsula, we have a lot of very small schools where it's K-12 all –in one building, and it might only be a couple hundred kids. The amount of latitude and freedom that they have within that building, for one person's decisions, like the food service directors, to sit everybody in that school. The school garden is big enough to provide something for a small school that everyone can have a taste of it. Another thing that really gets me excited is inclusivity, when everyone in the institution and in the community feels like they get to have part of the experience of local food.

What is the biggest challenge you have faced when working with schools and farms in the UP?

Abbey Palmer: Sometimes I wish that the work could happen faster. Sometimes I wish we were already seeing every school purchasing, that we saw every school being able to have relationships with farmers and that the farmers would be ready to have that relationship with the school. But the biggest challenge, beyond my own impatience, is probably that we could have more producers producing a greater volume of locally produced food, and still wouldn't meet the needs of the population here.

One of the challenges in the Upper Peninsula is just how much of our food we import while also recognizing that there's a great abundance of food here. People have been living here for thousands of years seeing this place as a place to come for food. Whether it was for maple syrup or for wild rice or for blueberries, there are really established traditions around a lot of the plants here. When I think about food service and school and what the school lunch looked like, what would it take to tell the stories of those foods and bring those foods into the lives of every student in the Upper Peninsula.

The biggest challenges are the amount of food produced that is able to make it into institutions, mostly for reasons that we lack some distribution networks for local food, and we don't have a lot of food processing infrastructure. It would be so cool for some of the farms to be able to freeze their broccoli or beans and to grow enough of those crops and know that they had a market for it and go into the schools. But that facility doesn't exist yet and is not accessible to those farms.

We also have only one USDA certified meat processing facility for an area that's about 33% of the land mass in Michigan. People drive a long way to bring their animals to our one USDA facility. There's work in all these different areas and people who are working on trying to do a feasibility study for a processing facility. Our friends at the UP Food Exchange and Northern Center for Rural Health and a lot of partners are planning and working on these things. But the biggest challenge for me is maintaining a really optimistic attitude about it when I’ve been in this work for about 10 or 11 years. Some of the things that we wanted 10 years ago still haven't happened.

What would be one step you recommend people take if they want to succeed in farm to school work?

Abbey Palmer: One step would be to find a way to have relationships with the teachers and with the food service directors. The connections there, the relationships, the friendships, the bringing each other cookies or dropping an email to say congratulations, I heard about this or that, that is the thing that has moved the needle for me. Being able to do this kind of work at all is because of relationships. People want to talk about this stuff.

In your work, what one important lesson have you learned about the food system in the UP?

Abbey Palmer: One of the prevailing narratives about the Upper Peninsula is that we have a very short growing season and very thin soil, or we don't have a lot of topsoil. One of our prevailing narratives says it's very difficult to grow food here because you can't do it for very much of the year, and you might not have a lot of great, deep, rich agricultural soil to do it in. I've learned that the innovation, the ingenuity, and the persistence of the people and the plants and the animals here means that it is possible to grow food for more of the year. It is possible to store and market those crops. We might still need to remember how difficult it can be with our long winters and not a lot of sunlight in the winter, but that doesn't need to be our prevailing narrative.

Zaire Parrotte: Awesome! You could definitely write a book about that.

Abbey Palmer: We can do it! We really can grow food for more of the year here and people can have a livelihood around that. It is certainly possible. Interestingly, there's a lot of people moving here right now, perhaps as a result of the pandemic, becoming interested in self-sufficiency or deciding that they wanted to leave the city that they live in, coming here and starting farms. That's kind of an interesting new development.

Zaire Parrotte: It’s like a new migration. That's really cool!

Can you share a memorable moment from a farm to school project that you’ve worked on?

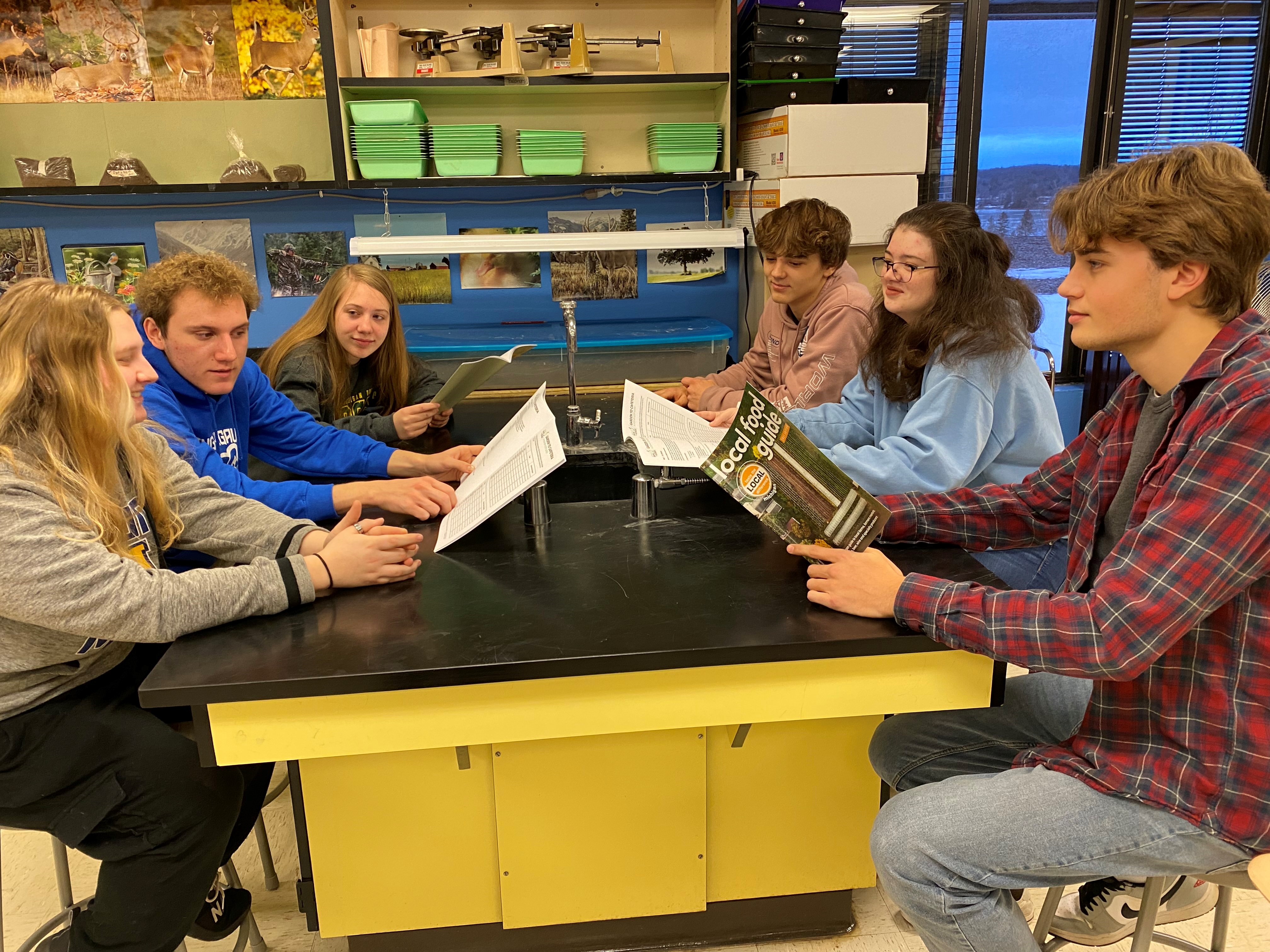

Abbey Palmer: Kids always say and do such interesting things, I’m trying to remember a particular one. Here's one of my favorite moments from the last farm to school project I worked on. I had the opportunity to join teachers in their classrooms to ask students the question “What would it take to get more local food into your lunchrooms?” These are students who have hoop-houses or school gardens and had the option of designing their own answer to this question of suggesting their own intervention after they had a chance to understand the constraints that the food service director was under and after they interviewed a farmer to understand what their concerns with the economics and the pricing are.

There came a moment when the students needed to choose between a couple of different interventions. They had proposed three different things [that] different groups had, and the students turned to their teacher and said, “We don't want to make this decision the way you might expect. We're not going to just vote on this and then move forward with the winner. We would like you to give us a class period where we can discuss amongst ourselves without too much butting in from the adults how we'd like to solve this issue of having 3 or 4 different solutions to this problem.” The teacher said “OKAY”, and he and I got to sit back and watch the students taking the decision-making process that we had taught them and utilized it with one another to come up with a project that was really their design. What made that so cool was just that the students felt empowered to ask for the time to decide together about something as important as what they eat for lunch every day and that the teacher without any hesitation said, “Yes, you're prepared for this. I want to give you this space to do that.” It was a really cool and powerful moment about sharing power.

Zaire Parrotte: Amazing! What grade was this?

Abbey Palmer: It was a high school class where it was mixed between sophomores and seniors, so it was multiple ages, but it was high school.

Zaire Parrotte: If that was an elementary school, I would like to visit that school myself! That's absolutely amazing! With a lot of work in farm to institution or farm to school, there has been a lot of talk about equity and how we could have an equitable lens. Since the beginning of my journey working with MFIN, I have always been a proponent of making sure that whatever decisions we make, we include the people who are being impacted by what we’re doing. That way, we're not perpetuating any type of decision-making strategies that have been harmful for many types of demographics and populations for thousands of years. That was a perfect example of giving people the space to decide what they want to do. In farm to school, our target is the students. However, we don't always give the students a choice and an opportunity to make those decisions. That’s really awesome.

Zaire Parrotte: I have one last question.

What is your favorite recipe using local foods?

Abbey Palmer: Oh my gosh! Favorite recipe for local? This past year, a friend of mine gave me some seeds from a hull-less (meaning no hull) pumpkin seed. You grow a pumpkin that contains seeds that don't have the hull, the seed coat. When you think of pepitas, they’re white and might be covered like a pumpkin seed. This plant grows just the seed without the seed coat. It's kind of a weird explanation but the point is you can pick up this squash, this pumpkin, and open it up and just eat the seeds right out of it without preparing them in any way at all. This was a new flavor experience for me because I didn't know how incredibly rich, buttery, and nutty these pumpkin seeds could be when they are 100% fresh. That is a weird local food experience, it's not exactly a recipe. It's just me standing in my garden, having opened up a pumpkin and now I'm just sitting over the pumpkin, checking it out and eating it. But that's definitely one of my new favorite foods, and I just put it into my garden plan that I want to grow those this year. I want to try to share them with the schools that have gardens because how cool would it be for kids to have that experience of roasting pumpkin seeds from a regular pumpkin and also trying these hull-less ones.

Zaire Parrotte: I’ve never heard of that. When you were explaining that my mind was trying to make sense of it.

Abbey Palmer: They need a new name, a hull-less acorn squash or a hull-less pumpkin doesn't make any sense, but the naked seeds are delicious.

Zaire Parrotte: Amazing! That concludes our interview with Abbey Palmer. Before we leave...

Do you have any final thoughts you would like to share?

Abbey Palmer: It was really a pleasure to talk with you, Zaire. Thank you so much for inviting me to talk on Faces of the Network.

Zaire Parrotte: Thank you so much for giving your time and sharing your experience with us!

Print

Print Email

Email