MSU Quantitative Fisheries Center meeting dire modeling, decision-making needs for Great Lakes fishery management

Nearly two decades ago, scientists at Michigan State University seized an opportunity to add their expertise in sophisticated quantitative methods to the fold through an initiative called the Quantitative Fisheries Center.

The Great Lakes are a freshwater resource unlike any other in the world, deeply embedded in Michigan’s culture and economy. In addition to being the planet’s largest freshwater system, they provide food, access to a wide range of recreational activities and are the basis of a $7 billion fisheries industry employing 75,000 people, according to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission (GLFC).

Protecting the health of the lakes and the wildlife that calls them home is of critical importance. Fisheries managers monitor more than 130 native fish species that inhabit the lakes, along with at least 34 non-native species — some of which have become invasive and begun to jeopardize the health of the ecosystem. According to the GLFC, another 61 species are threatened or endangered, requiring innovative management strategies to preserve and reestablish populations.

Nearly two decades ago, scientists at Michigan State University seized an opportunity to add their expertise in sophisticated quantitative methods to the fold through an initiative called the Quantitative Fisheries Center (QFC).

A critical partnership

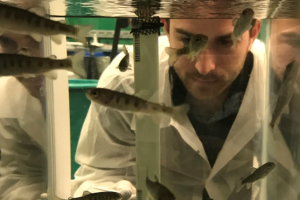

James Bence, the William E. Ricker Professor of Fisheries Management, and Michael Jones, the Peter A. Larkin Professor of Quantitative Fisheries, are the co-directors of the QFC. Bence is an expert in fish stock assessment methods, simulation modeling and ecological biometry — the analysis of biological observations using statistics. Jones specializes in structured decision making and simulation modeling, with an emphasis on how risk and uncertainty affect management.

“Addressing fishery issues requires good scientific information on how species will respond to management measures, and a key part of this is quantitative analysis of fishery data,” Jones said.

In 2004, Bence and Jones organized a meeting to propose the creation of the center that included William Taylor, then chairperson of the MSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and leaders from the GLFC and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR). With additional assistance from the MSU Office of the Provost, the QFC launched in July 2005.

Leading the charge with Bence and Jones is Travis Brenden, QFC associate director and a professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, who joined in 2006. His research focuses on stock assessment, biometry and simulation modeling. Faculty member Kelly Robinson, an assistant professor in the department, came onboard in 2016 and uses structured decision making in her work. The center also consists of 12 affiliate faculty and 16 graduate students and professionals.

Today, the center receives support from its founding partners, as well as several states bordering the Great Lakes, the Canadian province of Ontario, and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission. Additional MSU backing comes from MSU AgBioResearch, MSU Extension and the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The QFC also benefits from the Partnership for Ecosystem Research and Management (PERM), a program uniting MSU with fisheries and wildlife management agencies to preserve the state’s natural resources. Bence, Jones and Robinson’s positions are funded, in part, by PERM.The center’s primary objective is to provide research, outreach and training to fisheries management professionals through consultation and educational opportunities, while increasing the agencies’ internal modeling capacity. Bence said the QFC positions MSU scientists to do just that, with the goal of focusing on the agencies’ short- and long-term needs.

“The QFC was created to conduct increasingly sophisticated quantitative analyses to assess fish habitats and stocks,” he said. “We also formally consider the effects of risk and uncertainty on management decisions.”

Five non-credit online courses — covering topics such as modeling, structured decision making, management software, and data analysis using R (a statistical programming language) — are currently offered to management professionals. Some have been used in courses for MSU students as well, and the QFC is actively developing a number of additional online courses.

Delivering science-based recommendations

Research has been conducted on each of the Great Lakes, including more than 50 projects and 60 consultation requests over the last five years. These projects have been geared toward management of both commercial and recreational species, mitigating the effects of invasives, and conservation of threatened and endangered species.

Bence has participated in an advisory role for the Modeling Subcommittee of the 1836 Treaty Waters Technical Fisheries Committee (MSC). The 1836 Treaty of Washington determines fishery harvest in large portions of Lake Michigan, Lake Huron and Lake Superior between the state of Michigan and the Chippewa-Ottawa bands of Native Americans. A series of consent decrees over the years has governed how annual harvest amounts are regulated to avoid excessive mortality that could threaten fish populations.

Bence and his team have made recommendations on how to conduct assessments and how to weigh various sources of data. Among other tools, the MSC uses assessment models and simulation studies created by QFC scientists to help establish appropriate harvest levels.

For a separate project, Robinson is directing efforts on grass carp research in Lake Erie. Despite regulations in neighboring states prohibiting release in small ponds and aquaculture facilities, grass carp have been found in increasing numbers in Lake Erie since the 1980s. Robinson said they pose a number of problems, including reducing water quality by stirring up sediment, damaging wetlands used by other aquatic species and birds, and destroying commercial fishing nets.

Partnering with the MDNR, Robinson held structured decision making workshops with biologists, fisheries managers, university scientists and Asian carp researchers to identify objectives to combat further grass carp proliferation. Stakeholders discussed concerns around potential population growth, costs of control methods and economic losses from Asian carp activity. These conversations spawned management plans and helped to develop new tools, along with generating new funding streams for long-term control.

Bence said the urgency surrounding the QFC’s work has only increased over time due to funding challenges for agencies hiring experts in quantitative analysis.

“This need for assistance continues as a result of the severe shortage of quantitative fishery scientists, both nationwide and in the Great Lakes basin,” he said. “There are insufficient resources for Great Lakes fishery management agencies to hire dedicated quantitative analysts, so that’s where we come in.”

Print

Print Email

Email