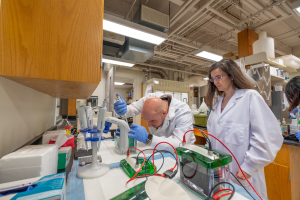

MSU researchers to explore symbiosis and co-evolution of fungi, plants and bacteria

A new research project led by Michigan State University scientists will explore the diversity, evolution and ecological functions of a fungi lineage critical to the success of terrestrial plant life worldwide, including agricultural crops.

East Lansing, Mich. – A new research project led by Michigan State University (MSU) scientists will explore the diversity, evolution and ecological functions of a fungi lineage critical to the success of terrestrial plant life worldwide, including agricultural crops.

Funded through a $1.75 million Dimensions of Biodiversity award from the National Science Foundation, over the next five years the team will study evolution of Mucoromycota, a diverse lineage of fungi found throughout the planet (including Antarctica), and their symbiotic relationship with both plants and bacteria.

Gregory Bonito, assistant professor in the MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, co-leads the project with fellow researchers Patrick Edger, assistant professor in the MSU Department of Horticulture, Bjoern Hamberger, assistant professor in the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Kevin Liu, assistant professor in the MSU Department of Computer Science and Engineering.

“Mucoromycota is the lineage of fungi implicated in the terrestrialization of Earth by plant life,” Bonito said. “Before plants had evolved roots, they were associated with Mucoromycota fungi, and they continue this association today. These fungi appear to aid in plant growth, plant stress resilience and soil health. Understanding the basis of these relationships is crucial to our continued study of plant diversity and functional biology.”

Many species of fungi in the Mucoromycota harbor intracellular bacteria. In order to acquire a deeper understanding of these tripartite (plant-fungal-bacterial) symbioses, Bonito’s team will inventory and isolate these fungi in samples taken from every continent. Though a technique called meta-transcriptomics, the research team will study symbiosis by analyzing how the expression of genes in these fungi, their associated bacteria and host plants change over time and under different environmental conditions. Advanced computational analyses of genome-based data generated through this project will enable the researchers to reconstruct the evolutionary histories among fungal, bacterial and plant symbionts. The resulting insights will shed light into the function and evolution of these ancient alliances, and will provide a glimpse into the origins of terrestrial life as we know it.

Mucoromycota are used by commercial enterprises as industrial workhorses, producing lipids and fatty acids that are the basis for valuable bioenergy and nutraceutical industries. While Mucoromycota have been studied for well over 100 years, recent developments in advanced sequencing and genetic technologies have rapidly accelerated the pace of research progress. This research will provide foundational knowledge about the genetic diversity and potential of these industrially important pathways and genes. Additionally, the intracellular bacteria living within Mucoromycota fungi could prove to be valuable sources of bioactive compounds, including those used in cancer treatments and other medical applications. The beneficial relationship of these fungi with crop plants also means that they have an important role to play in the development of sustainable agricultural practices.

“We want to understand the basis of how the fungi communicate with plants and bacteria, in order to create broad impacts,” Bonito said. “Understanding how certain gene expression networks contribute to plant fitness or lipid production, and how to regulate these networks, could lead to enormous impacts in agriculture, medicine and industry.”

Bonito envisions one day being able to use these fungi to encourage the early establishment of stable plant microbial communities, better equipping plants to withstand drought, disease and other damaging forces in agricultural and forestry plots. But as with any project that plumbs the fundamental relationships underpinning the natural world, new discoveries await around every corner.

“These organisms are living right under our feet, and you can grow them up out of the soil and discover something new every week,” Bonito said. “It’s exciting, dynamic and rewarding work. Every day brings surprises. You don’t know what exactly you’re going to get, but you know you may find something important.”

Print

Print Email

Email