Marc Hasenick isn’t interested in labels. He’s not concerned with being called “innovative” or “progressive.” Like all conscientious farmers, he simply wants to run a sustainable, profitable operation.

Hasenick co-manages a 4,800-acre farm of corn, soybeans and wheat with his father and brother. The operation in Springport, Michigan, is undoubtedly ahead of the curve. Each acre is rotated with a cover crop to enrich the soil with nutrients. The land is not tilled, a practice gaining popularity to preserve organic matter, enhance overall soil quality and improve water infiltration. Keeping heavy equipment out of the fields as much as possible also reduces soil compaction.

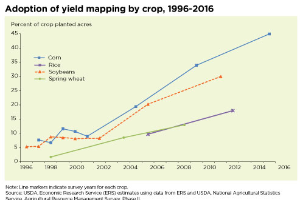

More than 20 years ago, the family made its foray into precision agriculture with a purchase of a yield monitor. It was also well before Marc — a 2010 graduate of Michigan State University (MSU) with a bachelor’s degree in crop and soil sciences — assumed a leadership role on the farm.

As technology advanced, the Hasenicks grew more interested in the benefits of precision agriculture, especially the ability to combine years’ worth of yield data with increasingly sophisticated strategies. In the process, they turned to MSU for assistance.

Doing the right thing at the right time

Bruno Basso, an MSU Foundation professor and MSU AgBioResearch scientist who studies the sustainability of row crop production systems, is working with the Hasenicks to broaden their access to modeling software and aerial imagery.

“You can’t manage what you don’t know,” he said. “Precision agriculture is about managing the spatial and temporal variability present in a cropping system. In other words, we need to understand how things are different from one area of the field to the next over the course of time. That requires compiling a lot of data and using modeling.”

Much of Basso’s work involves the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones. Through sensors, they collect crop data, including moisture levels, soil temperature and nutrient makeup. After seeing this wealth of information, Hasenick purchased a drone. The benefits to his farm were immediate.

“The UAV paid for itself the first time we used it,” Hasenick said. “We’ve had lots of yield data, but up to that point we’ve never had in-season measurements of the entire field. The UAV provided up-to-date information on how each portion of the field was performing, taking into account that year’s unique weather pattern. It added a dimension that we previously couldn’t have had.”

A goal of Basso’s is to help farmers like the Hasenicks make more informed decisions.

“Sooner rather than later, precision agriculture is going to be the only way to do agriculture,” Basso said. “To be sustainable, farming has to be profitable for the farmer, and the environment must be protected.”

Basso explained precision agriculture as “The Five R’s” of agriculture management: doing the right thing, at the right time, in the right place, in the right way, with the right inputs.

“Because variability is the norm rather than the exception, you want to deal with variability,” Basso said. “Plants growing in one part of the field are exposed to different conditions than those in other parts, so naturally you want to handle them differently.”

Several factors account for variability in the field, such as weather, soil, position in the landscape and the way the plants were managed. Sometimes farmers introduce an additional level of complexity through uninformed management.

Tracking variability has been a priority for Basso since he started studying crop modeling as an MSU student in the early 1990s. Since then, he developed a software program called the System Approach to Land Use Sustainability (SALUS), which models crop, nutrient, soil and water conditions over multiple years and various management styles. He also co-founded CiBO Technologies, a company that helps farmers make more educated decisions.

Access to this type of technology is groundbreaking for farmers like Hasenick. Basso believes that operations of all sizes can benefit.

“Working with Marc has been wonderful,” Basso said. “Cost isn’t really the barrier to implementing technology today because there are so many places to get it. The bigger problem is that many farmers aren’t risk takers, and they are reluctant to change the way they do things. Marc has been open to thinking differently, and I think he’s seen positive results from doing so. With all of the data we’ve gathered, we’ve been able to make prescriptive recommendations.”

Hasenick wants to continue working with Basso, whose popularity and expertise stretch well beyond Michigan. Basso has numerous international grants in places such as Europe, Africa and Australia, with farmers on all points of the technology spectrum. While some are using UAVs and crop modeling software, others are deploying handheld technology to learn more about the health of their plants.

Regardless of whom he’s collaborating with, Basso is sure to emphasize the environmental benefits of precision agriculture.

“We want to work with farmers all over the world to ensure that the economics make sense, but there is an ecosystem element as well,” Basso said. “As consumers demand more information about their food — where it comes from, how it’s produced — we need to be more transparent. Part of that is educating farmers on how they can both be profitable and protect the environment, something that’s good for everyone.

“The environmental side of precision agriculture hasn’t resonated as much with farmers, but it’s extremely important. If you do the right thing in your field, you not only make more profit, but you reduce the negative environmental impact of your inputs. It’s undeniable that ecosystem services are enhanced with precision agriculture.”

Print

Print Email

Email