MSU and MDARD plant labs unite to help Michigan plant industries thrive

MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics and MDARD’s Plant Pathology Laboratory have collaborated for more than a decade to diagnose plant problems and provide aid to growers.

East Lansing, Mich. — Less than 2 miles marks the distance between two plant laboratories that’ve contributed to an important partnership between Michigan State University and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD).

MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics and MDARD’s Plant Pathology Laboratory (PPL) work together to address some of the most pestilent plant problems that plague Michigan farmers.

Over 15 years ago, Ray Hammerschmidt, faculty coordinator of MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics and Professor Emeritus in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, invited Elizabeth Dorman, manager of MDARD’s PPL, to discuss a possible collaboration involving the state and university labs while attending the North Central Plant Diagnostic Network’s meeting in Chicago.

The regional network, part of the greater National Plant Diagnostic Network, is an association of plant diagnostic labs from six Great Lakes states, in addition to those from Iowa and Missouri. MSU serves as the primary hub and provides leadership for the region.

Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin — in addition to Michigan — invited their state department diagnostic labs to attend the meeting with their state’s land-grant university labs.

“This was the first time our region’s state department diagnostic labs and university labs were brought together,” Dorman said. “The meeting was designed to work on strengthening the partnership between the state and university labs.”

Since then, MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics and MDARD’s PPL have teamed up not only to identify and formulate management strategies for some of the state’s most troubling plant concerns, but also to share expertise and protocols with each other.

“The close working relationship between our two laboratories is yet another example of the collaborative, mission-driven approach common in Michigan agriculture,” said Dr. Tim Boring, MDARD Director. “For MDARD, this cooperation is crucial for us to certify export-bound commodities and for early detection of invasive species. The ongoing partnership is important not just for these activities, but for the standard demonstrated on a daily basis of delivering for our stakeholders.”

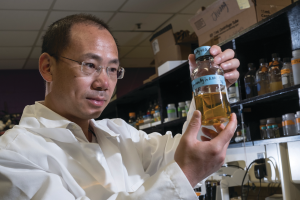

MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics was established in 1999 with funding support from Project GREEEN, Michigan’s plant initiative based at MSU and composed of Michigan’s Plant Coalition, MDARD, MSU AgBioResearch and MSU Extension. The lab uses a multidisciplinary approach to diagnose which pathogens, pests, nematodes, weeds and abiotic issues are affecting its clients, including growers, homeowners, industry professionals, campus specialists and regulatory agencies. From there, the lab’s dedicated specialists provide recommendations for how to control the issue.

MDARD’s PPL also tests plant samples to discover which plant pathogens and pests are at play, but its priorities lie more in facilitating the inspection of Michigan plant products for certification and trade, as well as safeguarding Michigan plant industries through regulatory action. When the lab doesn’t have the testing standards or expertise to perform a specific test, Dorman and her staff work with MSU’s lab to get results.

“Our lab doesn’t have the ability to offer nematology, so MSU can fill in that gap for our growers who are shipping to another country requiring a nematode lab test for its export certification,” Dorman said. “For example, MDARD had a sample that needed a plant weed identification as part of an investigation. With the access MSU’s lab has to the herbarium on campus and its weed science diagnostician, Erin Hill, those samples were able to be identified quickly.

“It’s important we have them close by. We don’t have to re-mail samples; we can drop them off. They’re a mile down the road. They’re a phone call away. It helps move samples quickly and effectively.”

To gauge what issues may or may not be affecting Michigan plant industries, MDARD’s PPL conducts field surveys across the state to check for signs of pathogens or pests disrupting production.

In 2006, Michigan encountered its first case of plum pox, a severe viral disease that causes harm to stone fruit such as plums, almonds and peaches. A few years later, with support from MSU’s lab and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service — among help from other institutions and agencies — MDARD’s PPL gathered about 80,000 samples from roughly 240,000 trees to survey for the presence of the disease. In 2009, it was eradicated from the state.

“There’s no way I could’ve done that by myself, no matter with how many students I hired,” Dorman said. “We really needed the extra lab space to expand the survey and get it done. Because of that assistance, we were able to declare Michigan free of the plum pox virus after year three of its first detection, which was critical for our growers and their markets.”

Along with being able to rely on each other for assistance, the two labs also work together to develop innovative protocols and techniques for sampling. Hammerschmidt said that doing so has helped advance how both labs operate.

“There’s a lot of communication between both labs that exists in a very synergistic way, even if our labs have slightly different missions,” Hammerschmidt said.

One instance of where the labs have teamed up to cultivate a protocol is at the molecular level.

Jan Byrne, plant pathology diagnostician for MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics, said MSU and MDARD have explored molecular approaches for detecting pathogens and pests.

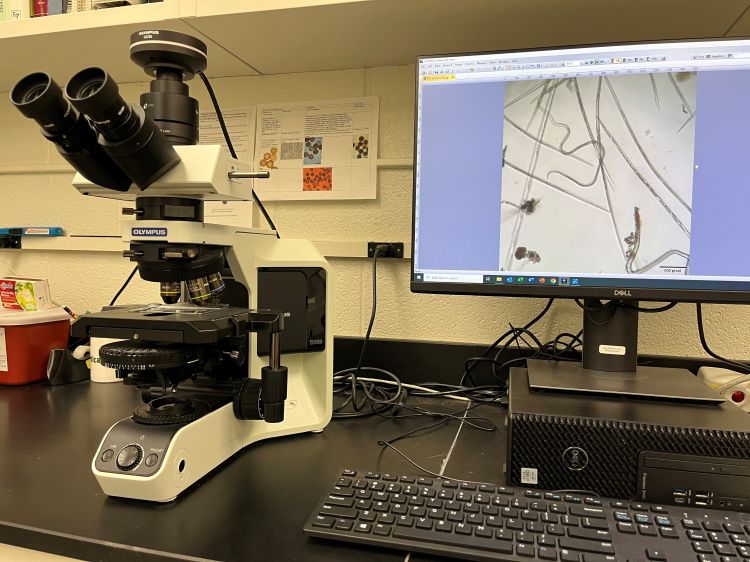

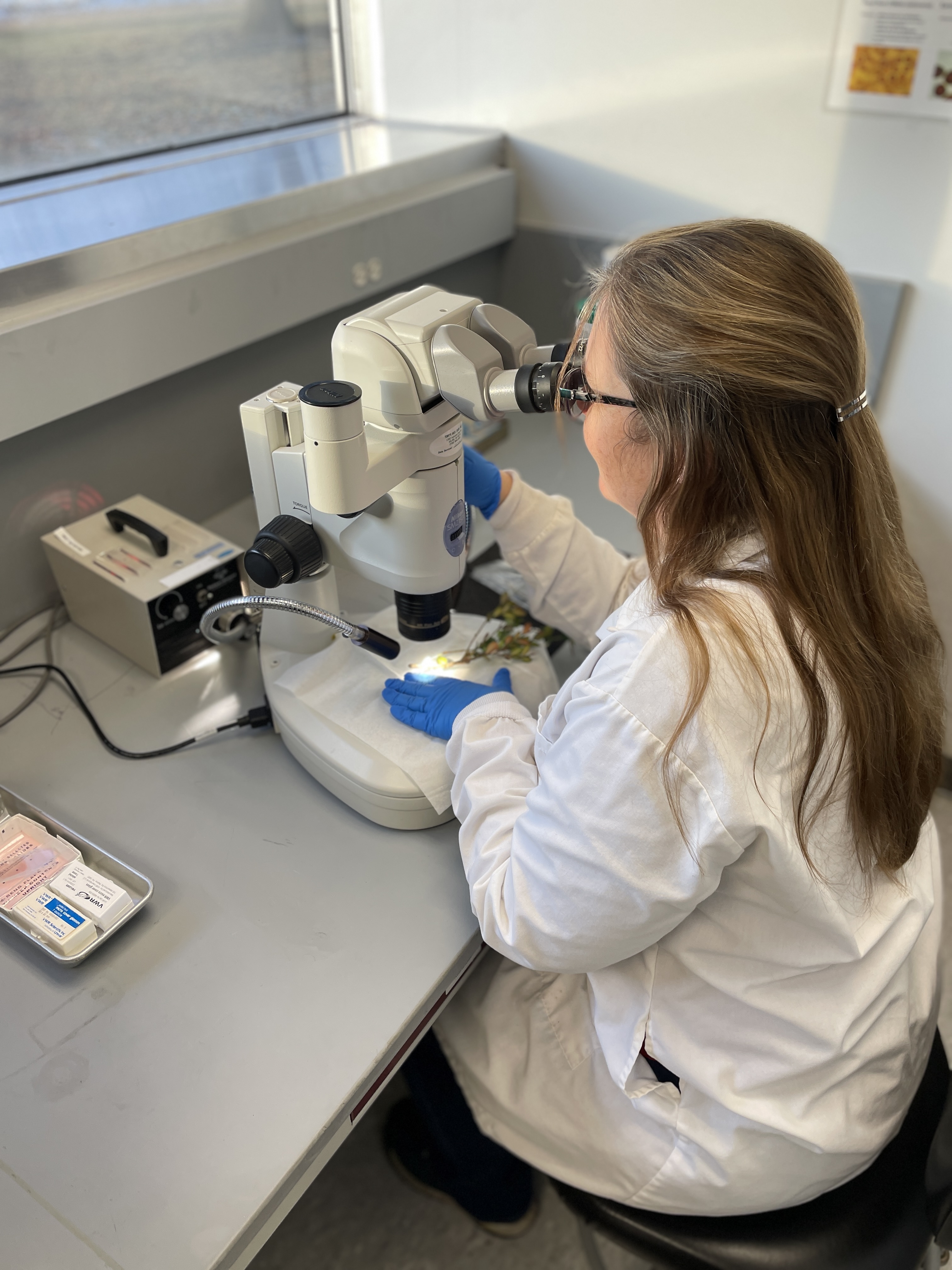

Beech leaf disease, a destructive foliage disease brought upon by nematodes targeting beech tree species, first appeared in Michigan in 2022. From the MSU Plant and Pest Diagnostics team, nematode diagnostician Angela Tenney and molecular plant pathology diagnostician Laura Miles have collaborated with MDARD scientist Stefanie Rhodes to implement a molecular tool for uncovering the disease. Through this process, they’ve learned when molecular testing might be better served compared to morphological testing — observing plant tissue under a microscope — and vice versa.

They’ve similarly experimented with ways to molecularly track boxwood blight, a serious fungal disease also new to Michigan that infects ornamental boxwood shrubs.

“We started with morphological techniques — looking for the pathogen in plant tissue — but felt there had to be a better way to find the needle in the haystack, so our labs have worked on sharing a protocol for molecular detection of that particular pathogen,” Byrne said.

According to Byrne, the most significant aspect of the labs’ partnership — and the purpose for having it — is that it ultimately helps Michigan growers overcome the challenges they’re facing in a successful and timely manner.

“Because we have this great relationship, we’re able to work behind the scenes on problems, so our clients may never know that collaboration even happened,” Byrne said. “If we don’t have a piece of equipment or are out of a supply, we’re able to work with each other to do the testing and get results for our clients sooner rather than later.”

Michigan State University AgBioResearch scientists discover dynamic solutions for food systems and the environment. More than 300 MSU faculty conduct leading-edge research on a variety of topics, from health and climate to agriculture and natural resources. Originally formed in 1888 as the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, MSU AgBioResearch oversees numerous on-campus research facilities, as well as 15 outlying centers throughout Michigan. To learn more, visit agbioresearch.msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email