MSU researcher working to address emerald ash borer

Invasive species research aimed at supporting management plans across the state

Researchers didn’t see emerald ash borer (EAB) coming when it first appeared in Michigan in 2002, and the spread has been devastating -- killing tens of millions of ash trees in Michigan. The troublesome beetle most likely entered the U.S. through wood crating and/or pallets used to ship cargo from Asia and has led to a full-blown plant health emergency.

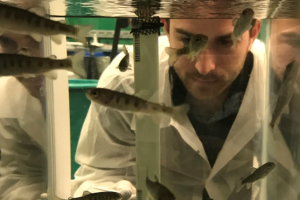

Deborah McCullough, MSU forest entomology professor, has worked with other researchers, technicians and students on EAB population dynamics, spread, impacts and control.

“We collected tree rings across a 5,800 square mile area in southeast Michigan and found that emerald ash borer had arrived in the Detroit metro area near Westland and Garden City by at least the early 1990s, but it wasn’t discovered until 2002,” she said. “EAB is now in 35 states, five Canadian provinces and is considered the most destructive and costly forest insect to ever invade North America.”

McCullough, who has a research, teaching and MSU Extension appointment, collaborates with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD), the U.S. Forest Service and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). Her role is to provide research and options for those who manage forest pest issues.

“As we become aware of emerging problems, those feed into my research,” McCullough said. “It’s kind of a two-way street where the research can address emerging questions and through MSU Extension we can get that information out quickly and practically.

“In the case of EAB, there was very little known about this insect when it was discovered, and in many ways, we started from scratch. We needed to learn the life cycle of the insect and develop methods to survey it, control it, and to tell people confidently what they could expect about impacts.”

McCullough has led numerous projects related to EAB, ranging from detection and survey methods, population dynamics and spread, host range and interspecific host preference, ecological and economic impacts, systemic insecticides to protect landscape trees, and strategies for area-wide management.

EAB wasn’t the first plant health emergency, and it won’t be the last. McCullough and her team are working on hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), a tiny, sap-feeding insect native to Japan. Populations of HWA are in five counties in the state, mostly along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

“This insect has killed thousands of hemlock trees in the eastern U.S. since the 1950s,” she said. “In New England and on the east coast, we know that when the hemlock trees die, everything changes. It affects important wildlife habitat along with soil chemistry, other vegetation and streams and rivers. Eastern hemlock trees are abundant in northern Michigan and are really vulnerable to HWA. Nobody wants to see this invader spread, so many of us involved with forest health are collaborating on survey and control tactics to help contain it.”

McCullough and her team have a HWA foundation of research to build upon.

“In the east, people have been dealing with this for decades, so we look at what they’ve done and what can we apply here in Michigan. We analyze where we need additional research because things like climate and forests are not exactly the same in Michigan. Part of our work includes adapting what has been successful in other areas and making sure that we have solid and practical tools here.”

Over the past 10 years, McCullough has worked with a team from across the country, including ecologists, forest entomologists and economists, to indentify over 450 invasive forest insect species and the ones causing the most ecological and economical harm.

“At the time, we found 454 established non-native forest insects in the U.S.,” she said. “Fortunately, only 62 are considered to be damaging.”

“When you look at forest pathogens, there were only 16 species, but all of them cause damage. I think that it partly tells you that people give a lot of attention to insects. You can see and catch insects. People like moths, butterflies and beetles. But pathogens, unless that pathogen is causing problems – causing trees to decline or die – nobody can know what might be floating around out there until someone notices a problem.”

McCullough often works with MSU forest pathologist Monique Sakalidis. The two are now working to address oak wilt, an increasingly pest in Michigan.

Oak wilt is fatal for all the species in the red oak group, such as northern red oak and pin oak. It presents itself by rapid wilting and loss of leaves in mid-summer, and tree dies within a few weeks.

Dead oaks will eventually produce small mats of spores, known as pressure pads, due to ruptured bark. They are not always immediately obvious – but are marked by a slight swelling and a vertical crack in the bark.

Several species of native sap-feeding beetles are attracted to these sweet-smelling spore mats. The tiny beetles squeeze through the crack in the bark and feed on the spores. Spores will stick to the bodies of the beetles. These same beetles are also attracted to the sap produced by fresh wounds on healthy oak trees and introduce the oak wilt into the tre. Once an oak tree is infected, the fungus moves into the roots, then spreads through root grafts, infecting even more trees.

Effective and practical options to reduce damage caused by oak wilt requires a team approach. McCullough and Sakalidis have worked with Bert Cregg, a tree physiologist at MSU, along with forest health specialists from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. New research to evaluate various options to protect healthy trees and slow the spread of oak wilt infections will get underway this spring.

McCullough’s research lab focuses on forest insect ecology and management and runs along a continuum of relatively basic to applied studies to enhance insect and forest ecology while generating practical information to address infestation. Most activities in recent years have involved invasive forest insects, largely because of the economic and ecological costs associated with several major insect pests.

Print

Print Email

Email