Empowering through the generations

Endowed positions provide long-term research funding and attract high-quality faculty members to advance their fields and prepare the next group of influential educators

One of the wealthiest women in the United States during the early 20th century, Matilda R. Wilson had many passions that she supported through philanthropy. A primary beneficiary of Wilson’s generosity was Michigan State University (MSU). In addition to significant monetary donations, she gave her time and expertise to MSU during a period of dramatic growth for the university.

Wilson was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1883 but moved with her family to Detroit shortly afterward. She married John Dodge, the legendary automotive innovator, in 1907. Together they purchased a 320-acre farm near Rochester, Michigan, called Meadow Brook. Dodge died unexpectedly from influenza in 1920; in 1925, Wilson married Alfred Wilson, a lumber broker. The couple moved to Meadow Brook and oversaw the building of a mansion on the property, while acquiring more land that grew the farm to 2,600 acres.

Roaming the land were draft horses, pigs, cattle and poultry. Looking to expand her poultry stock in the 1920s, Wilson solicited the assistance of an agricultural agent named John Hannah. He became the president of MSU in 1941, and Wilson’s support increased. She served as a trustee, becoming a trustee emeritus in 1960. To aid the university in broadening its reach, Matilda and Alfred donated most of their land, including their home, and a $2 million endowment to MSU. The new MSU presence in Oakland County would eventually become Oakland University, an independent institution beginning in 1970.

Wilson died in 1967, but her work with MSU was not finished. Most of her assets went to the Matilda R. Wilson Fund, which ultimately provided the university with $1 million to create the Matilda R. Wilson Chair in Large Animal Clinical Sciences. Another $2 million established the Meadow Brook Chair in Farm Animal Health and Well-being, a second endowed faculty position that honors Wilson’s devotion to animals. Additional money from the fund has gone toward infrastructure and renovations of buildings on the MSU campus.

A pioneering approach

Endowed positions are vital to the prosperity of any university. They attract talented educators and ensure that research and educational initiatives are of the highest quality. MSU is near the bottom of the Big Ten conference in the number of endowed faculty members, a ranking university leadership is looking to change.

MSU launched the Empower Extraordinary campaign in October 2014 seeking to double its endowed professorships from 100 to 200. Donors like Wilson are essential. Just ask Ed Robinson.

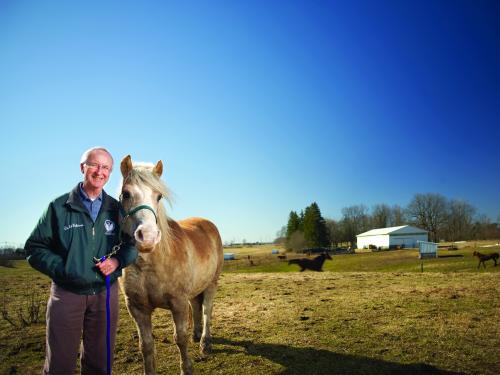

Despite never meeting Wilson, Robinson understands the passion she had for animals — especially horses — better than most. He was the first to occupy the Matilda R. Wilson Chair in Large Animal Clinical Sciences position, the inaugural endowed professorship in the College of Veterinary Medicine. The role gave him the funding and freedom to achieve what seemed like a pipe dream at the beginning of his career.

He grew up in a small town in the northwestern county of Cumbria, England. The son and grandson of livestock auctioneers, Robinson had a love of animals and was captivated by medicine. Combining those two concentrations, he ventured to London and earned a veterinary degree from the Royal Veterinary College at the University of London.

After coming to the U.S. and completing an internship at the University of Pennsylvania, Robinson was offered the opportunity to join the veterinary medicine clinic at the University of California, Davis. It was there that he decided to pursue his doctorate.

After coming to the U.S. and completing an internship at the University of Pennsylvania, Robinson was offered the opportunity to join the veterinary medicine clinic at the University of California, Davis. It was there that he decided to pursue his doctorate.

Robinson arrived at MSU in 1972, joining the Department of Physiology and the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences. The lack of research with tangible results on improving the health of horses had bothered him for years. He was determined to change the field.

“When I came to MSU, I had this crazy idea that I wanted to build a research lab focusing on the respiratory system of horses,” Robinson said. “I had a couple of labs in mind to model from but they were in human medicine, and I was naïve enough to ignore the realities of funding.

“In terms of long-term funding of equine health research, you might get a grant for three years where you just get going and then some other topic becomes hot to the funding agency and you lose your support. You may be doing good science, but you may no longer be studying a topic that’s as relevant in the eyes of the funding sources.”

Undeterred, Robinson remained diligent, a resolute focus that was rewarded. After 16 years, dozens of published articles and several graduate veterinarians trained in research at MSU, he was named the Matilda R. Wilson Chair in Large Animal Clinical Sciences in 1988. With a constant stream of monetary support, Robinson’s program soared to international acclaim.

Alongside his team of graduate students and colleagues, Robinson continued to study heaves, a horse disease similar to asthma in humans. His innovative research focused on understanding and improving treatment of chronic respiratory diseases has revolutionized equine medicine.

The horse airway exploration in his lab evolved to also include recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, or roaring, which is a paralysis in a portion of the horse’s voice box. Roughly 11 percent of thoroughbreds are affected by the disease. Research on this condition continues in collaboration with Cornell University.

“The bigger the horse, the more affected they seem to be,” Robinson said. “We were interested initially in how we could treat it, but the genetics became the focus later on as we began to see that pattern. I could do this research purely because the Matilda R. Wilson Fund allowed me to gather blood samples from a large number of affected and healthy horses. The fund has a hands-off approach to the chair position, which allowed me to build a program.”

Robinson retired from MSU in 2014, leaving behind a legacy that will endure long into the future — not unlike Matilda Wilson’s. Just don’t expect one of the pioneers of equine medicine to stay away from research forever.

“I vowed that I would not go back to work much at all for a year once I retired,” Robinson said. “Now that it’s been a year, I’m beginning to do some professional things again outside of MSU.”

Today, Robinson is involved with a committee of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. Meeting for the first time in November, the group is working on a disease called exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage that affects racehorses. Specifically, the committee is planning future research that may find better approaches to prevent bleeding.

“A horse is basically an oxygen transporting machine to get oxygen into its muscles,” Robinson said. “It has a maximal oxygen consumption per kilogram that’s three times higher than ours. So its respiratory and cardiovascular systems are working full out during exercise. With the large amount of blood that’s being transported from the lungs to the muscles, the lung begins to leak and over time develops some chronic changes in the blood vessels, a finding first made at MSU with the help of the Wilson endowment.”

Professionals once believed that just 2 percent of horses bled during exercise, typically manifesting as a bloody nose. But the introduction of the flexible fiberoptic endoscope to detect blood in the lungs showed that most horses are affected to some extent.

“The next step is asking the question, ‘What’s next with the disease?’” Robinson said. “You can’t lessen the cardiac output or oxygen consumption of a horse and still have a racehorse.”

As Robinson continues to make discoveries in the field, he credits his colleagues, students and the Matilda R. Wilson Fund for vaulting his career to the next level.

“Endowments help to attract really top-quality faculty,” Robinson said. “The idea is that the person then goes and gets bigger extramural grants and brings prestige to the university. You start to attract great graduate students, allowing your program to really take off. That’s the essence of what creates a great program. You’re training people and they’re going on to do amazing things. They probably help your program more than you help them. But you can’t do anything without the resources.”

Carving a new path

When Robinson became the Matilda R. Wilson Chair in Large Animal Clinical Sciences, there was no precedent. No legacy to uphold. No standard-bearer for the position. That’s not the case for Adam Moeser.

His appointment began in April 2015, and he’s been charged with continuing to cultivate his nationally and internationally recognized research program. The flexibility of the Matilda R. Wilson Fund allows him to do exactly what Robinson did before him — shape the role around his research interests and train new scientists.

Unlike Robinson, Moeser wasn’t sure which career pathway to take as a child. A devout Boston Red Sox fan growing up in southeastern Massachusetts, his first love was baseball. He pursued the sport as a Division-I student-athlete at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, while majoring in veterinary and animal sciences. Realizing his fastball wasn’t quite fast enough, he focused on his studies and a part-time job on a farm working with sheep and pigs that were being raised for agricultural purposes and biomedical research. His career choice was solidified.

“I was gaining hands-on experience and knowledge of farm animals, and at the same time I was delivering animals to research hospitals in the Boston and New York City areas,” Moeser said. “This was something that really influenced the development of my career because I came to see the importance of animals from the agriculture and research standpoints. I saw the tremendous influence that animal research can have on both animal and human medicine.”

A fascination with discovery was born. Wanting to know more about the intersection of animal and human health, Moeser traveled down the East Coast to North Carolina State University and pursued a master’s degree in animal science. His interest was in the gut — how animals absorb nutrients, and how the gut acts as a barrier between the animal and the outside world.

Though his initial focus was on nutrition, he became increasingly concerned with the gut and its defense mechanisms. Thus began his pursuit of a combined Ph.D. and doctor of veterinary medicine degree at N.C. State, where he joined the faculty as an assistant professor upon graduating in 2008.

His experiences on the farm and in clinical settings helped him recognize that stress is a major factor in triggering many gut-related diseases in animals. Through his early research, Moeser understood that when animals encounter stressors, there are pathologic changes in the gut and clinical signs that are remarkably similar to those of human gut disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome. Stress-related gut diseases in animals and humans are very common and cost billions of dollars annually to healthcare industries. Learning more about how stress negatively affects gastrointestinal function has been his quest ever since.

Moeser was satisfied with his progress at N.C. State, having developed a recognized research program, received multiple National Institutes of Health grants, and obtained an associate professor position. But when he heard about the opening at MSU, it proved to be a move he simply couldn’t pass up. The chance to grow his research program was a dream scenario.

“One of the things that really attracted me to MSU is the diversity in research groups,” Moeser said. “There are excellent faculty members in animal science, veterinary medicine, human medicine, basic sciences. It’s all on one campus. That’s something that I had not experienced previously. It opens up all kinds of new avenues of research collaboration.”

His job now is to advance the knowledge of stress and gut disease through collaboration with other professionals, graduate students, postdocs, funding sources and the Matilda R. Wilson Fund.

“We’ve long known that stressors in the environment for animals and people are a major risk factor for the development of many diseases, particularly gut disorders,” Moeser said. “My research is focused on understanding the biology behind that stress response. There’s so little known about how stress impacts the GI tract. The human health side of this comes in through our basic research of animal models that translate to humans.”

Moeser is seeking to leverage the endowment of his position to maximize extramural funding. He wants to use the reputation developed by faculty members such as Robinson as a launching pad for his program, both in expanding research and training students.

“I believe the true impact of this position, even more than research advancements, is training the next generation of scientists,” Moeser said. “In the future, if I can train 20 to 30 additional investigators who are out there doing excellent work in this field, that’s going to have far greater impact than my individual research. Ed (Robinson) has been so supportive, and thanks to this opportunity at MSU, I feel like my career trajectory has been elevated and accelerated.”

Print

Print Email

Email