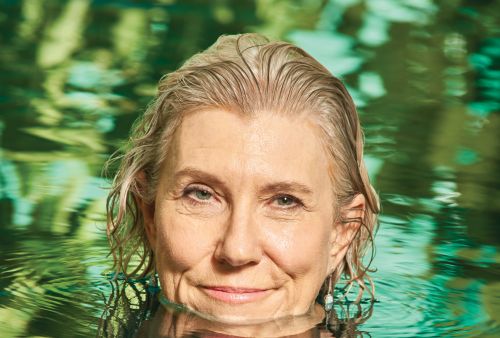

Joan Rose is accomplished. And she improves lives every day for people she doesn’t even know. But her story isn’t finished.

She thinks there’s a revolution on the horizon. “There are a lot of things that aren’t finished,” she said. “That’s what keeps me up at night. We’re at the point where something really revolutionary could happen around water.”

Rose is Michigan State University’s Homer Nowlin Endowed Chair in Water Research, co-director of the Center for Water Sciences, and co-director of the Center for Advancing Microbial Risk Assessment. She supervises the Water Quality, Environmental, and Molecular Microbiology Laboratory (WQEMM).

The Rose WQEMM laboratory consist of two labs, one in Natural Resources for general water quality testing and the second in Plant and Soil Sciences for environmental molecular microbiology assays. The Natural Resources’ water quality laboratory houses the only EPA certified Cryptosporidium and Giardia program for water testing in the state of Michigan.

For 30 years Rose has been investigating water quality around the world. Last year, she was recognized with the Stockholm Water Prize, an international award often compared to the Nobel Prize for it prestige.

As a kid, Rose said she was always restless – and a bit of a go-getter. “I just felt like I hadn’t found my place,” she said. “I remember making a lot of lists of things to do when I was really young.”

That feeling of restlessness left her when she found herself looking into a microscope studying water microbiology. She claims the restlessness is gone. It might just have been redirected . . .

“There’s always another question to be answered,” she said. “And with water degradation throughout the world, I hope we can move fast enough. I worry even more now that I have grandkids. Even in just 20 years, how stressed is the world’s water going to be?”

Rose has been recognized for her work by the EPA, agencies in Canada, Singapore, Japan, and the state of Michigan; the list goes on and on. She travels internationally at a clip that would exhaust most people, often investigating waterborne outbreaks that threaten lives and communities.

At first, Rose said she didn’t think about the impact of her work. “You don’t’ think about how important the work is until you’ve walked into a place where there’s been a water-related outbreak and people are dying,” she said. For Rose, that happened in 1993 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, during the largest waterborne disease outbreak in documented US history. While the root cause was never confirmed, Rose was on the team that found the epidemic was caused by Cryptosporidium oocysts that passed through the filtration system of one of the city's water-treatment plants, arising from a sewage-treatment plant's outlet two miles upstream in Lake Michigan.

Over two weeks, 403,000 city residents had become ill, and 104 deaths were attributed to the outbreak. “It is devastating when you’re in a community that’s losing its most sensitive populations – babies, the elderly, those with compromised immune systems,” she said.

Notwithstanding Milwaukee – and the recent Flint water crisis, Rose said Americans live in a relatively stable environment when it comes to water. “You don’t really see it until you travel,” she said. Working on water across the globe was what brought Rose to MSU.

“As soon as I got here I was able do international work,” she said. “I can work on a global level – and I can work in the Great Lakes, which is essentially my backyard. My position as the Nowlin Chair gives me a freedom to match research dollars. The opportunities here are so much greater than anywhere else.”

So what’s the future of water research? Climate change? Feeding global populations? Yes to all, but Rose suggests that the biggest opportunity for innovation lies in work in wastewater. She said for every dollar invested in wastewater, there’s a four dollar return.

“Groundwater is part of this whole picture, too,” she said. “It’s often ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ but it’s the biggest source of water for agriculture, and you don’t know the value until it’s gone.”

Rose knows the power of water. It’s a source of life, livelihood and hope. Water affects more than agriculture and lush landscapes; it affects people and societies.

“When we stress natural resources like water, we will run into hard economic times,” said Rose. “Look at the Middle East; when it dried up, everyone left. And when young people don’t see a future, they look for one. Hard economic times can push people toward instability – political and personal.”

Rose wonders about the connections between environmental protection and health. “When people don’t feel well, do they take the same precautions they would when they do? Do they use all that we’ve developed to help make water safe? Maybe we need to focus on heath, too.”

While her restlessness might feel quelled, for Rose the biggest questions just keep her working. “What will we do when this isn’t the land of plenty anymore?”

Print

Print Email

Email